Why and how to get organically certified?

Whether one can get organic certification or not is seen by the extent to which a given production system follows or complies with organic production principles and practices. Certification is not compulsory and is needed only if the market demands it. For example, to sell in certain organic shops or on certain organic markets, the farmer may need to have some sort of certification and to export the products as organic, the farmer may often need to have third party certification by an organic certification body having the required accreditation.

Group discussion:

Discuss with all participants the advantages and disadvantages of certification. Ask for example the following questions:

- Which are the benefits of organic certification?

- When does a farmer need organic certification and when is it not necessary?

When do I need certification?

As there are numerous ’eco-friendly’ campaigns, certification is one way consumers can rely on what is being said. Organic certification is a marketing tool and is especially important if your products are exported as most of these markets require it. It is a process that tests for fraudulent practices within farm systems and, therefore, ensures that everyone in the organic supply chain adheres to the organic production principles and practices. Therefore, organic certification will provide the confirmation that the organic supply chain is in compliance with organic standards and hence can carry an organic label or seal.

The organic seal confirms that the product is grown according to organic standards and regulations. Organic certification thus protects organic farmers and organic production, by ensuring that producers stick to the organic standards and prevents fraudulent traders, especially when the consumer is very far away from the producer. Thus, a trust is developed between consumer and product that is otherwise difficult to build.

To be certified as organic, the farm must be inspected by a representative of a certifying organisation and assessed against an organic standard or regulation. There are several labels that correspond to these various standards and regulations and can be displayed on the products when they are certified accordingly. It is often important to choose a certification that will grant the use of a logo or label that is well recognized by the ultimate target consumers.

Group discussion:

Build groups of 3 participants.

Let each one chose to discuss the pros and cons of Participatory and third-party certification. Evaluate in a final discussion.

Which certification system do I need?

There are two main types of certification relevant to organic farmers:

- Participatory certification through a Participatory Guarantee System: this is mainly relevant for the local or domestic market.

- Third party certification conducted by an independent (third party) organic certifier, also called certification body. This is relevant for some domestic markets, but mostly export markets.

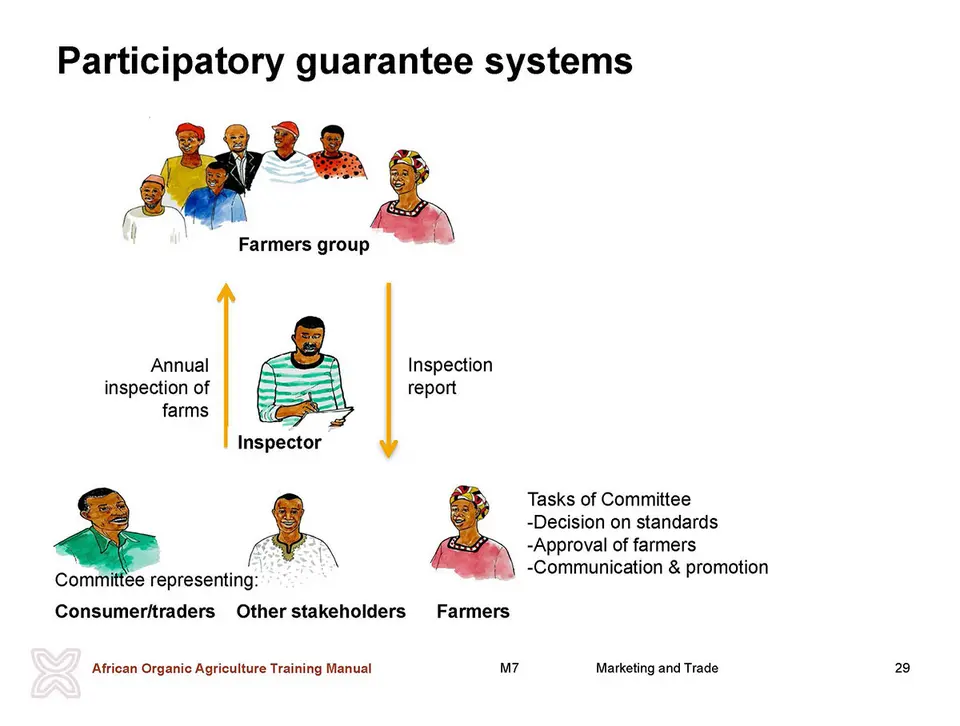

IFOAM defines Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) as locally focused quality assurance systems which certify producers based on active participation of stakeholders and are built on a foundation of trust, social networks and knowledge exchange. Participatory Guarantee Systems are also sometimes referred to as ’participatory certification’.

PGS enable the direct participation of producers, consumers and other stakeholders in:

- the choice and definition of the standards (which can be simpler versions of the national standard, but sometimes also contain additional requirements decided by the group);

- the development and implementation of verification procedures;

- the certification decisions.

PGS have developed independently in various countries and continents and hence every PGS system is different and locally adapted. Nevertheless, there are common key elements and features among all the PGS systems:

Key elements of PGS:

a. Shared vision

A fundamental strength of the Participatory Guarantee System lies in the conscious shared vision that farmers and consumers have in the core principles guiding the program. The vision can embrace organic production goals as well as goals relating to fair trade, respect for ecosystems, the autonomy of local communities and cultural differences.

b. Participation

Participation is an essential and dynamic part of PGSs. Key stakeholders (producers, consumers, retailers and traders and others such as NGOs) are engaged in the initial design and then the operation of the PGS. In the operation of a PGS, stakeholders (including producers) are involved in decision making and essential decisions about the operation of the PGS itself. In addition to being involved in the mechanics of the PGS, stakeholders, particularly the producers are engaged in a structured ongoing learning process, which helps them improve what they do.

c. Transparency

Transparency is created by having all stakeholders, including farmers and consumers, aware of exactly how the guarantee system works to include the standards, the organic guarantee process (norms) and how decisions are made. This does not mean that every detail is known by everyone but rather they have at least a basic understanding of how the system functions or have a way to find out.

d. Trust – ’integrity-based approach’

The integrity base upon which PGSs are built is rooted in the idea that producers can be trusted and that the organic guarantee system can be an expression and verification of this trust. The foundation of this trust is built from the idea that the key stakeholders collectively develop their shared vision and then collectively continue to shape and reinforce their vision through the PGS.

e. Learning process

The effective involvement of farmers, retailers and consumers on the elaboration and verification of the principles and rules not only leads to the generation of credibility of the organic product, but also to a permanent process of learning which develops capacities in the communities involved.

f. Horizontality

Horizontality means sharing of power. PGSs are intended to be non-hierarchical. The verification of the organic quality of a product or process is not concentrated in the hands of a few. All involved in the process of participatory certification have the same level of responsibility and capacity to establish the organic quality of a product or process.

A typical PGS involves organic farmers, consumers and possibly other stakeholders such as staff from supporting NGOs, extension services staff, consultants, government representatives, university staff, etc. Farmers are typically organised in local groups which are responsible for ensuring that all farmers of the group are following the PGS standards and processes. Each farmer receives an annual farm visit by at least one other farmer of the group, sometimes accompanied by another stakeholder (e.g. consumer). Results of the farm visits are documented and serve as a basis for the farmer group to take decisions on the certification status of each group member. Documentation summaries and certification decisions are typically communicated to a higher level, for example to a regional council or national council representing the PGS stakeholders. This council sometimes endorses certification decisions taken by the groups or more generally approves each local group and grants them the use of the PGS logo if any. The higher level also decides on organic standards to be followed and represents the PGS towards external actors such as the government and IFOAM.

As compared to third party certification, PGS provide the following benefits to small farmers:

- It provides a collective support that will help the farmer in his daily life. For example, the group can provide support to its members for production, for marketing and for finances. They can be perfectly integrated in self-help groups and farmer field school systems.

- It requires less paperwork and is usually cheaper than third party certification.

- It facilitates the creation of linkages with local consumers and hence helps to grow the local demand for organic products.

However, PGS certification is not always acceptable to all buyers. Certain buyers such as supermarkets or exporters will require third party certification to accept the products as organic. Moreover, PGS requires the farmers to be actively involved in the group (i.e. participating in regular group meetings and the farm inspection of other farmers).

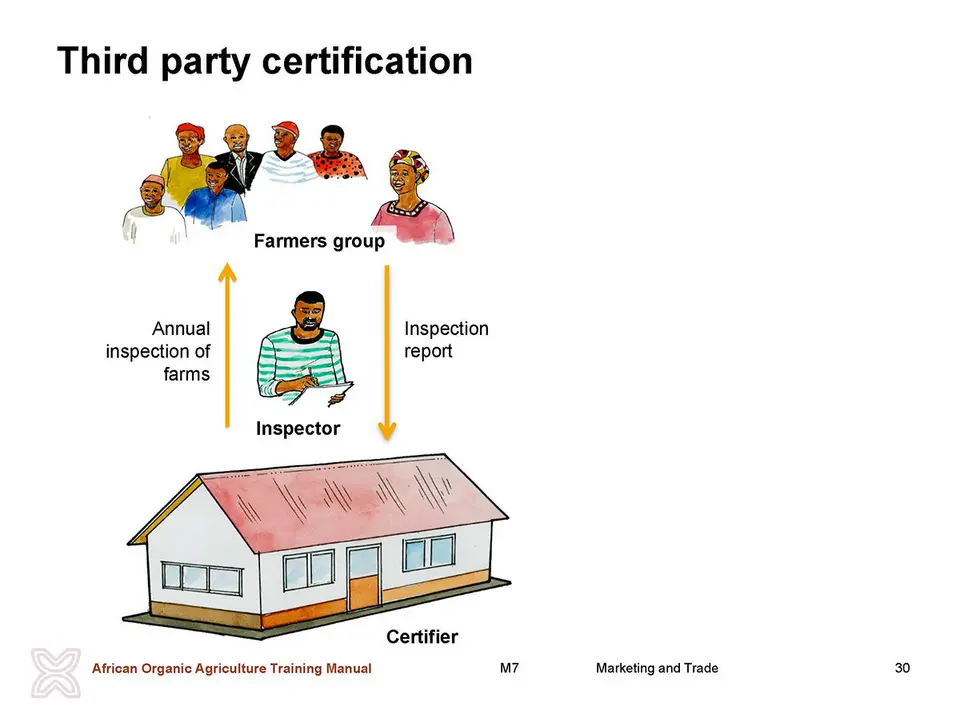

Third party certification

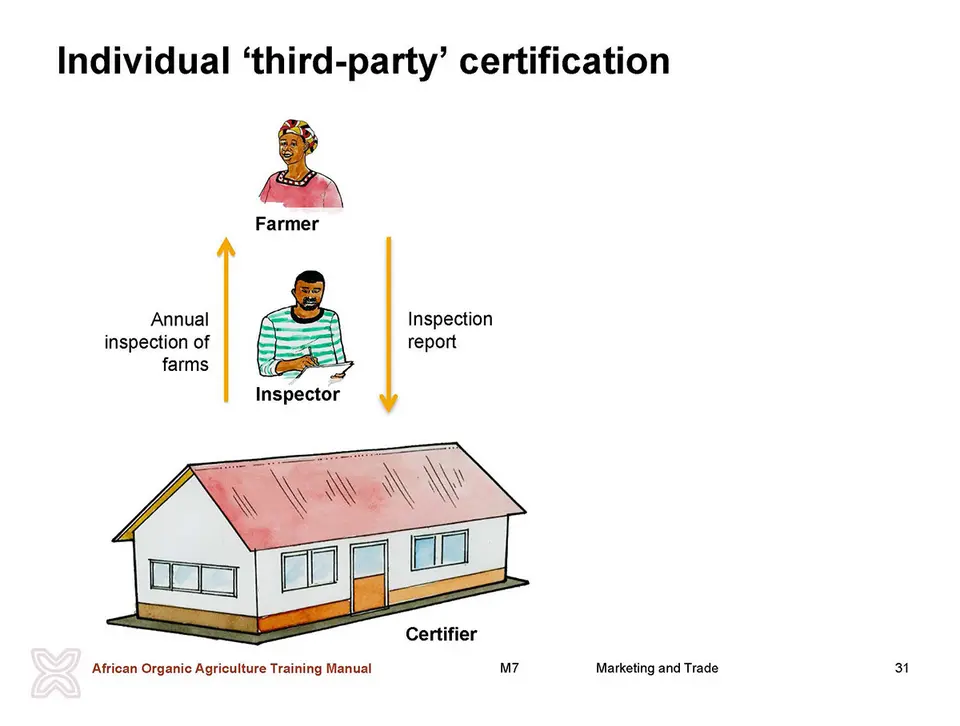

Third party certification is a service usually provided by a certification body to its clients for a fee. The service consists of an on-site review of farming practices and of the corresponding records and documentation kept by the farmer, to verify compliance with the relevant organic standards. This inspection is done at least once a year and is performed by an organic inspector hired by the certification body.

There are two scenarios under which organic producers can be third party certified:

- Individual third party certification, whereby the farmer alone signs a contract with the certification body and will obtain his or her own organic certificate.

- Group certification, whereby a group of farmers (either organised in a cooperative way or organised by a buyer) is managing an Internal Control System (ICS) and requests certification as a group.

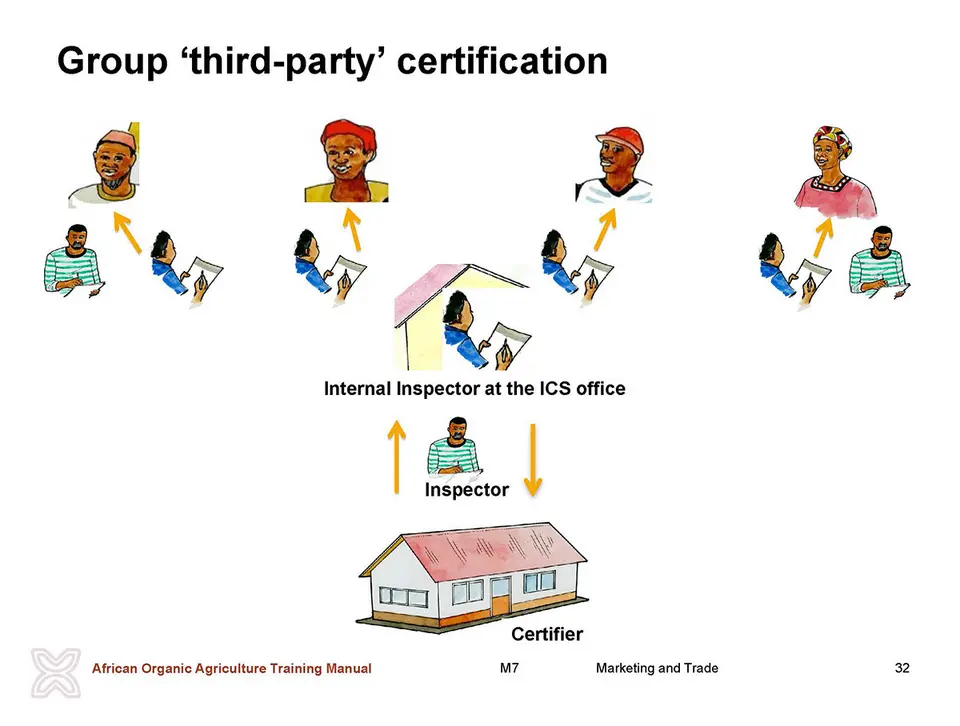

Group certification consists of a system of combined internal and external control for the collective certification of a group of small producers. It implies that:

- An Internal Control System (ICS) managed by the group ensures individual internal inspections of each farmer annually and establishes one documentation system common to the whole group.

- An external certification body inspects the documentation and the good functioning of the ICS and carries out sample re-inspections of farmers to evaluate the quality of the internal inspections.

- The certification body delivers a collective organic certificate that is owned by the group and not by farmers individually. The cost of group certification is shared among the group members (which lowers the cost significantly), but the products certified can only be marketed as organic through the group.

The purpose of an ICS is to bring down the cost of organic certification for small-holders by establishing a group that can do much of the monitoring itself. Then the certifier’s job is just to see that the group processes and data collection are working well and to check a small number of the farms. The objective is not to provide ’easy’ certification; the same organic rules must still be followed. But by carefully setting up the group and its rules, the regulations can be simplified to such an extent that even farmers with a low level of education are clear on the rules they must follow and the data that must be kept and by whom.

Group certification is typically used for groups of small-holders producing one or few common commodities for export. Groups have usually at least 30 to 50 members, but there is a great variety in the size of the groups. What is required is that the groups are quite homogenous: composed of farmers in geographical proximity, with similar production systems and with a joint marketing channel for the produce they want to have certified as organic.

What must I do to get certified?

Before applying for certification, the farmer or farmers group should attempt to conduct a self-assessment as below:

- Full application of organic practices on the farm has been tried out for at least one year and good knowledge and experiences have been developed;

- There is a target market which requires organic certification (which kind?) and offers enough return to compensate for the time and cost of being certified.

- Under organic production, the farmer or group of farmers have the particular products required by the organic market in sufficient quantities;

- The farmer or group of farmers has financial resources to pay for at least two years certification costs before they can start marketing them as organic.

Conversion Period

An important aspect of the process to become certified is that farmers who wish to engage in certified organic production need to go through a conversion period. This refers to the time that a farm has to use full organic production practices before it can be certified. The conversion period usually starts from the date that the farmers registered and signed an agreement committing themselves to following organic standards. The conversion period can be achieved in one to three years. When no agro-chemicals have been used in the last 3 years, conversion can be achieved in just one year. In farms or places where external inputs have been intensively used, the conversion period will be three years. The certifier sets out a conversion plan for each farm, which needs to be followed. It is, therefore, important to make early contact with the certifier to know the actual approach towards conversion and specific requirements. The conversion period is often costly for the producer because extra costs are made, mainly for certification, while the produce cannot bear the certification label which would give them higher market value.

a. The process of individual third-party certification

If the desired market requires third party certification against a particular standard or regulation, the farmer(s) should:

- Identify a certification body able to provide the required organic certification. Not all organic certification bodies have the required approval to certify, for instance, for the EU market, NOP market or the JAS market. It is highly advisable to choose a local certification body so long as it is able to deliver the required certification. Local certifiers understand local conditions better and probably are cheaper because they use local staff. The prices and services of several certification bodies should ideally be compared before a choice is made.

- Make an initial application to the certification body and pay an application fee.

- Normally, the application will ask for a description of the cropping history of each field or fields, a conversion plan for the farm (s) and or a livestock management plan for each livestock enterprise.

- An inspection visit from an inspector is carried out on the farm(s) and a report is prepared for certification approval by the certification committee of the certification body.

- Records of inputs must be kept and each year the farmer (or the farmer group in case of group certification) has to submit an annual report describing all activities of the year including all inputs and harvest/sales.

- Inspections are carried out annually and a certificate is granted for each inspection year. Farmers make an annual payment to the certification body for this service.

b. The process of group third party certification

If a group of farmers (for example, organised under a cooperative), would like to be certified as a group for one or few crops which they sell jointly, they should:

- Approach the national organic agriculture movement (NOAM) in their country, if it exists, or otherwise contact supporting NGOs or capacity building institutions working on organic agriculture, to start building up a relationship and to obtain more literature on group certification. These organisations may recommend a training organisation to assist you. The certification body is not allowed to do any training itself, as this is considered a conflict of interest.

- Work first on ensuring that all the group members produce organically and in compliance with the appropriate standard.

- Then work on group and documentation processes. With the farmers, develop and record the methods that they use. This must include the conversion rules, the rules for incorporating new farmers and their minimum requirements (e.g. target crops). Develop the contract that each farmer will sign to enter into the group. Contact the certification body to request the templates which the group needs to use and a complete list of their requirements.

- Elect or designate the relevant officers, who will do the internal inspections at least once a year. Sometimes they can be extension officers who are also likely to be involved in ongoing training of the farmers. In that case, they should never inspect farmers they have trained.

- Elect or designate an Internal ICS Management Committee, probably with some of the leaders of the association.

- Apply for certification to the identified certification body and implement all the requirements requested by them.

- Group certification may become complicated for the groups to handle if they are not well organised. Only strong groups and well organised groups have the capacity to manage the Internal Control System and can succeed to obtain organic certification in this way. They also need a considerable pre-financing capacity to invest in setting-up the system and go through the conversion period before financial returns can be obtained.

Steps to inspection and certification

A number of steps are required to certify a farm, a processing company or a trading company. It starts with a learning phase that includes investing time in getting familiar with the relevant organic regulations and implementing the various farm methods that comply with these regulations. And ends with a certification agency issuing a certificate verifying the farm’s or company’s compliance with the organic regulations. The following describes steps to be taken that involve inspection and certification of a farm. For a processor, a trading company or a distributor, specific issues need to be considered (see also previous chapters of this module).

1. Conversion planning - The first step is to get familiar with the organic regulations and standards, and learn what is and what is not allowed for every activity in farming, food processing, labelling and trade. A farm may then, based on these requirements, need to learn new technologies and correspondingly modify its farming methods. A typical example would be using compost instead of synthetic fertilizers or using natural predators instead of chemical pest management. This is part of the conversion planning that needs to be elaborated on together with the support of an experienced advisor at least one year before the first organic inspection is to take place. The conversion plan should include the following information:

2. The decision to pursue organic certification - The farmer’s family makes a decision on whether or not to certify the farm based on the conversion plan analysis. It is important to discuss the results of your conversion plan and your decision with farmer colleagues and with partners in the market chain–especially with potential customers, an advisor experienced in organic farming as well as a certification body agent. Farmers need to especially consider income needs and personal interests of all family members. As with all larger farm management decisions, the decision to convert to organic farming needs to be considered carefully in order to safeguard the future of the farm.

Group discussion:

Build groups of 3 participants and let them discuss their situation:

- Where are they in their decision-making pro-cess?

- Are they at the very start of the process or did they already apply for certification?

- What are the questions that appear during the steps leading to organic certification?

- How does one answer these questions?

Let the groups present the results of their discussion and conclude with a final discussion.

In case of doubts or specific needs, an inspector can make additional, unannounced visits to the farm to check specific issues such as application of pesticides, get additional documentation or visit the farm when the crops are harvested.

6. Certification - The inspector delivers the inspection report to the agency certifier. The certifier reviews the inspection report with all annexes (map and records and conversion plan). The certifier determines whether the farm will be approved for organic certification or not. If yes, the certifier issues a certificate, stateing the list of products that may be sold as organic. The farm may now sell its products as organic, using the labels agreed upon with the certification body. The product labels must identify the certifier and information about the producer.

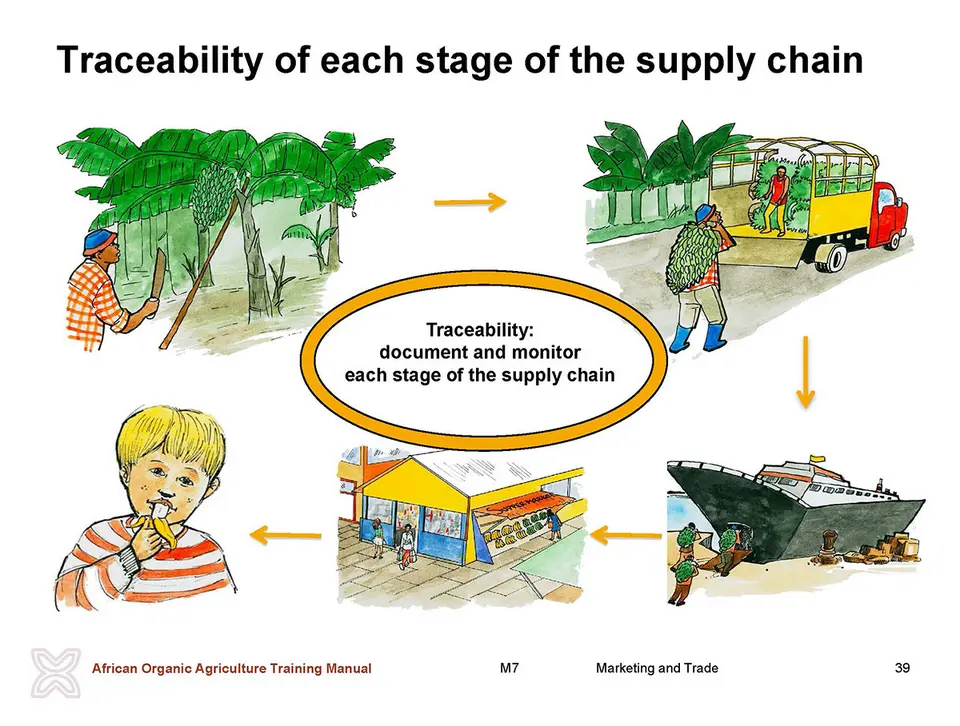

7. Traceability - All operators of an organic product chain need to be certified organically: producers, processors, traders and retailers. The regulations require all the stages of food production to be monitored in order to protect consumers against fraud. Traceability systems are used to identify products, their origin and their location within a supply chain. These systems also enable a company to recall products in case of any suspected fraud or a product’s contamination. In the case of organic exports, certification bodies monitor each stage of the supply chain and have to document the traceability in the transaction certificate, to be presented from the exporter to the importer.

Discussion with an inspector:

Invite a competent certification body inspector to present the benefits and costs of certification as well as a detailed example of the procedures involved. Let the participants discuss all related questions.

How to select the right standard and certification?

In answering this question, two additional questions are required:

- How can a producer decide which certification or certifications to apply for?

- When is the right time to make this decision?

- The answer to these questions is directly related to the potential markets for the organic products. However, the target market is not usually known in the first stages of conversion and is thus difficult to foresee certification requirements.

For example, a farmer just beginning the organic production will typically have to undergo a conversion period for two to three years (depending on the specific crop, the agricultural practices applied on the land before conversion and the actual standard or regulation to be observed). During this time, a farmer generally does not have a clear idea of who may purchase the products. Unfortunately, the first thing a potential trader usually inquires about is what certification the organic production has attained. This leaves it to the farmer to decide on certification before a buyer has been determined a potential bottleneck for facilitating trade.

Farmers and processors with high investing capacity can certainly choose to acquire at least the obligatory certifications for the main organic markets. Some small and medium farmers or farmers’ groups in developing countries who have access to international cooperation funding can also choose to do the above.

For other small and medium farmers or producers with less access to support, a less costly way of dealing with this challenge is probably to pursue the following:

- acquire knowledge about the different regulations and standards needed to access the main markets;

- ensure that agricultural practices applied on the farm do not contradict any of the main relevant regulations and standards (although this could restrict organic agricultural practices);

- document the conversion period since this documented proof will be necessary for certification;

- as the conversion period nears its end, the farmer is then in the position to put organic products on the market and this is the best time to choose to certify according to the requirements of a certain market.

Selecting the right certification body

A certification body (CB) is a service provider that should be chosen according to considerations of quality and price. Although this may seem evident, farmers often see inspectors and certification bodies as some kind of police force or superior authority that must be feared and not questioned, rather than a service body working for their benefit. Furthermore, traders or international organisation representatives simply inform suppliers which CB they trust or prefer, imposing a certain choice on the supplier. This situation is slowly changing as certification bodies in developing countries begin to develop expertise and recognition and more choices emerge. The new EU regulations are expected to have a positive impact on this situation as they incorporate more transparency into the processes of accreditation and surveillance of certification bodies.

In any case, farmers or farmers associations should evaluate a number of things before choosing a CB:

- The number of standards and regulations a CB is accredited to offer - The more certifications possible, the better. If a CB is able to offer certification for all major markets, no other CB will be required; however, alliances with other CBs can also remedy the need for multiple certifications.

- Efficiency and flexibility in meeting farmers’ needs - (to the extent that regulations will permit). Simplified procedures, well-trained (and preferably local) inspectors, inspecting once for multiple certifications and a commitment to timelines for each part of the process are important ways that certification bodies can make the process easier for farmers.

- Prestige and recognition - Certification is intended to guarantee transparency, impartiality and compliance with standards and regulations. Therefore, if all stakeholders in the value chain do not fully trust a CB, this can then threaten a farmer’s capacity to sell products and, in some ways, defeats the purpose of certification.

- Accessibility and availability - Between visits from inspectors, questions on standards or regulations may arise and a CB should be readily available to address and answer general questions and concerns.

- Price - Although it should not be the most important issue, undoubtedly the price of certification is an important consideration.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.