Health and disease

Why prevent disease

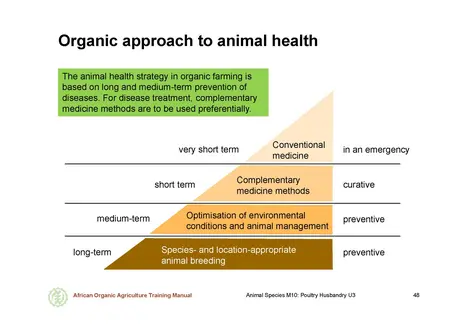

Maintenance of health in organic poultry farming primarily relies on the long and medium-term prevention of diseases and health problems. These can include those caused by infectious agents, the birds’ environment and nutrition, stress, and genetic factors. Besides being a cornerstone of organic farming, disease prevention ensures both human and animal safety, animal welfare, and ultimately better profits for farmers.

Preventing disease in poultry helps prevent the spread of zoonotic diseases (diseases spreading from animals to people or vice versa). These include diseases like salmonella, a bacterium that lives in the intestines of poultry and is spread in the faeces. The bacterium usually causes no symptoms in the birds, however, in humans, salmonellosis (the most common cause of “food poisoning”) causes diarrhoea and fever, and sometimes more severe symptoms. Other diseases such as Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI; in humans commonly known as “bird flu”), a virus that infects the birds and is spread through the faeces and respiratory secretions, can cause severe disease and death in both poultry and humans. Therefore, prevention of disease helps to keep the animals, the farmers and the community safe.

Disease prevention also ensures animal welfare by preventing painful and debilitating disease, injuries, and death. This not only shows respect for the animals and the goods and services they provide, but is also practical. While disease prevention may require time for flock observation and cleaning, it leads to considerable time and cost savings in the long run.

When a disease occurs in a flock, farmers must act quickly. They will have to put all routine tasks aside to quarantine sick birds, perform detailed observations of symptoms, and contact a veterinarian, community animal health worker or neighbour knowledgeable in poultry health. Ideally, a diagnosis of a curable disease is made and organic-approved medications are administered. Where organic-approved medications are not available or effective enough, synthetic medications should be used in interest of the animals.

In case of diagnosis of a non-curable and highly infectious disease, all the birds must be culled and all the premises must be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected. Such incidents are stressful, time-consuming and costly.

Careful prevention of diseases also reduces the need for the use of antibiotics on a regular basis. While the prophylactic use of antibiotics and other conventional medication to prevent problems is not allowed in organic production, their curative use is permitted when natural remedies do not have the required efficiency. However, it is important to note that each time antibiotics are used, resistent bacteria are selected. Over time antibiotics become less effective, or even ineffective, especially, if the antibiotics are not applied properly. Antibiotic resistance is increasing worldwide, both in animals and humans, and is becoming a problem in human health management. The best prevention of antibiotic resistance on a farm is to minimise the use of antibiotics by implementing proper prevention measures against diseases.

The keys to a healthy flock

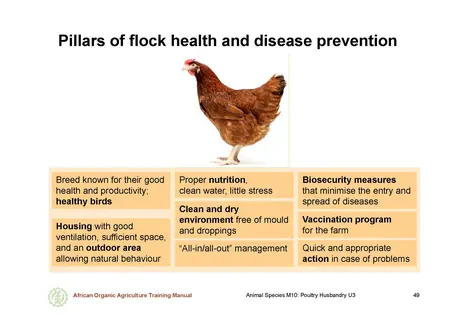

A good management system is the key to a healthy and productive flocks. A good management system ensures both healthy and disease-resistant birds and a clean, safe and healthy environment for animals and humans. The pillars of flock health and disease prevention are:

- Healthy birds that are bred for good health and productivity (Chapter 6)

- Proper nutrition, clean water and little stress (Chapters 2, 3 and 4)

- Housing with good ventilation, sufficient space, and an outdoor area allowing natural behaviours (Chapter 3)

- Robust cleaning procedures that ensure a clean and dry environment free of mould and droppings (Chapter 3.7)

- If possible, an “all-in/all-out” management strategy (Chapter 5.2.1)

- Biosecurity measures to minimise entry and spreading of diseases on the farm (Chapter 5.2.2)

- Quick identification of problems and appropriate action (Chapter 5.3)

- Vaccination program (Chapter 5.4)

All-in/all-out management

The “all-in/all-out” management method is recommended, where possible. The method relies on the introduction and removal of entire flocks. Between flocks, a thorough cleaning and disinfection of the empty house is performed. The cleaned facility is then stocked with birds of the same age. All animals of the flock will stay in the facility either until they reach slaughter weight in the case of broilers, or the end of the laying period in the case of layers. Then, all the birds are removed, and the facility is cleaned and disinfected before the next flock is brought in. Flocks with animals of different ages is only recommended for mother hens with chicks.

One of the main advantages of the “all-in/all-out” method is the reduced risk of disease introduction by new birds that are added to the flock. This method is not applicable in all cases, but the idea should be considered when planning the facilities.

Biosecurity measures

Biosecurity measures aim to prevent diseases from entering the farm, and from spreading within the farm. The all-in/all-out method discussed above is one example of a biosecurity measure. Biosecurity measures do not need to be complicated, but do need to be fully understood and strictly followed by the farmer, workers and visitors in order to be fully effective.

How do diseases enter and spread on the farm?

- In or on new purchased birds (infected eggs, chicks or adult birds)

- On hands, shoes, clothing or vehicles of visitors that have been on or in contact with sick or infected birds

- On hands, shoes, clothing or the vehicle of a veterinarian or animal health worker that has been in contact with sick or infected birds

- In or on wild birds, neighbourhood poultry, or other wild or domestic animals (i. e. cats, dogs, mice) that have been in contact with or fed on sick or infected birds and interact with the flock

- On hands, shoes, clothing or equipment used by the farmer as he/she travels between pens of birds

- In feed or feed components bought in or stored on the farm under unhygienic conditions

- Via biting insects, mites or ticks that have visited sick or infected birds

Because diseases caused by viruses, bacteria and parasites can easily enter a farm in various ways, these are often undetected. Nevertheless, all possible measures should be devised to minimise the entry of diseases. While it may not be practical or possible to implement all measures on a farm, farmers should try to implement as many biosecurity measures as possible.

General biosecurity recommendations

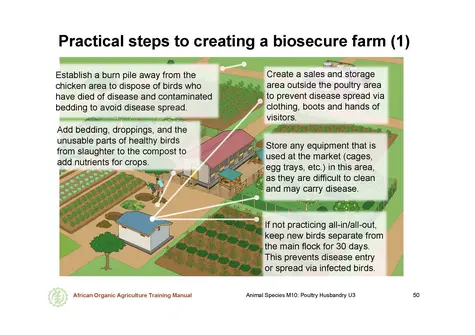

- Establishment of a burn pile: The establishment of a burn pile far enough from the chicken facility that the smoke will not blow in allows to dispose of birds who have died of disease and of contaminated bedding from those birds to avoid disease spread.

- Composting: Used bedding, droppings and the unmarketable parts of healthy birds from slaughter (feathers, beaks, etc.) can be composted and turned into a valuable fertiliser for crops. Care needs to be taken that wild birds and other predators and scavengers are excluded from the compost pile, as they can transmit undetected diseases.

- Sales area outside the farm: If sales of birds or eggs, or other products are done from the farm, the sales area should be set-up outside the perimeter fence of the farm. This reduces the risk of disease entry via clothing, boots and hands of visitors.

- Cleaning of all equipment used outside the farm: If sales are done from a market, all equipment (i. e. cages, egg trays, etc.) needs to be thoroughly cleaned, disinfected, and dried before entering the “clean” part of the farm. Used cardboard egg trays should not be introduced into the farm, as they may be contaminated and cannot be properly cleaned.

- Quarantine house: If no all-in/all-out method is practiced, a quarantine house should be established where new birds can remain separated from the main flock for 30 days.

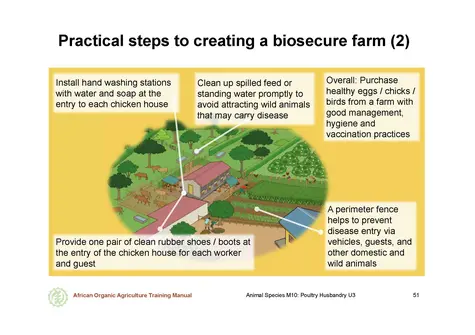

- Secure sources of supply: Only healthy eggs, chicks and birds should be purchased from a farm with good management, hygiene and vaccination practices.

- Perimeter fence: A perimeter fence should be installed around the chicken house and the outdoor run to prevent disease entry on the tires of dirty vehicles, dirty clothing and footwear of guests, free-range poultry, dogs and cats.

- Separate housing of different species: Birds of different species (e. g. ducks, chickens) should be housed separately.

- Washing stations: Hand washing stations with water and soap should be installed at the entry of each chicken house.

- Clean shoes/boots: A pair of clean rubber shoes/boots should be available at the threshold for entering the chicken area for each worker and guest. Before entering the facility, everyone needs to change from the “dirty” outside shoes to the “clean” rubber shoes inside. The rubber shoes/boots should be cleaned and disinfected regularly.

Observing the flock daily for signs of disease allows for rapid detection and ideally allows the farmer to quickly quarantine sick birds, consult a veterinarian or community animal health worker, diagnose, and treat the disease before it becomes severe with natural remedies before synthetic drugs such as antibiotics are required.

Biosecurity should be made a key element of the farm’s routine by following the following steps:

Daily biosecurity checklist for poultry farmers:

- Starting with the youngest birds: In case of more than one flock on a farm, work (feeding, cleaning, etc.) should always start with the youngest birds, the older birds, and end with new birds to the farm and finally sick birds. Such a procedure prevents disease spread within the farm from older animals to chicks, who are more susceptible to disease.

- Removal of spilled feed: Any spilled feed from indoor or outdoor areas needs to be removed. This helps to prevent disease entry via wild birds or other animals like rats and mice looking for food.

- Removal of standing water: Standing water surfaces from indoor or outdoor areas should be removed. This helps to prevent disease entry and spread by infected stinging insects.

- Check for illnesses: All chickens should be checked daily for illness. Chickens who appear ill should be isolated promptly. This prevents spread of the disease to healthy animals (see Chapter 5.4).

- Disposal of dead chickens: Chickens that died from illness must be disposed of by burning. They should never be eaten or fed to other animals. If many birds have died and veterinary services are available, the dead birds should be taken to the office to determine the cause of death. This is necessary to decide on the further steps to control the disease.

Discussion on biosecurity measures

Discuss in groups the implementation of biosecurity measures on the participants’ farms. Invite the participants to discuss the following questions:

- What biosecurity challenges have you faced, and how have you dealt with them?

- Which biosecurity measures have you implemented, which not?

- What new biosecurity measures might you consider after this training?

Handling of the birds

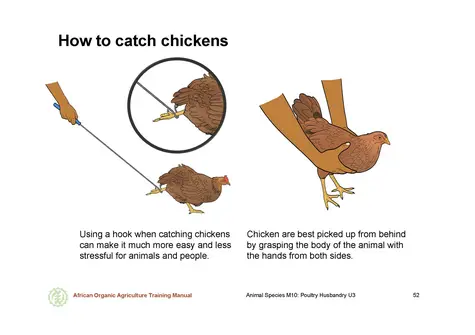

Chickens are easily stressed. Therefore, good handling is necessary to prevent problems in production, health and product quality.

Chickens should get used to humans from an early age. Inspections of the animals at least twice per day should be combined with gently handling individual birds. Birds who are handled from a young age will be easier to examine and less prone to stress later on.

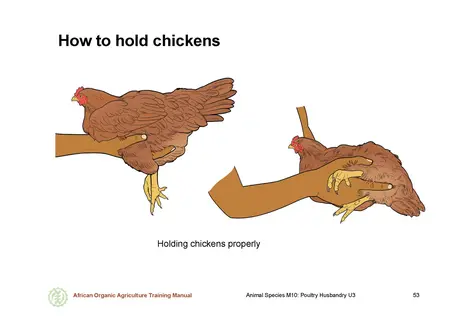

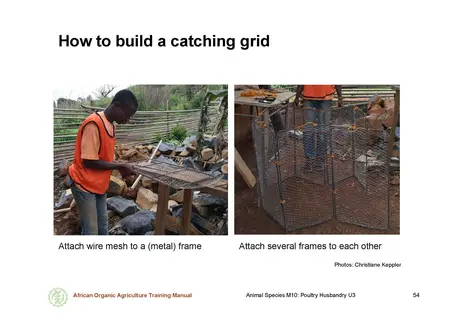

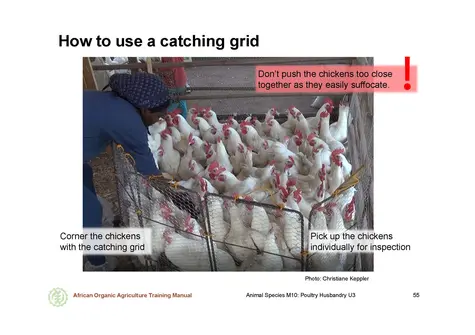

Any bird that shows signs of illness or injury should be individually handled and inspected. If the chickens are used to being caught and don’t tend to panic, they can be picked up gently by placing one hand over each wing to prevent excessive flapping. If a bird cannot be easily caught, a tool such as a catching grid or a poultry hook can be used to catch individual birds without disturbing the flock too much. For close inspection, one can rest the chicken on a hand and forearm while maintaining a gentle but firm grip on the chickens’ legs so that it can’t escape.

If a larger number of birds need to be caught, for example for selling or slaughtering, they are best picked up from their perches at night, using as little light as possible. A small headlamp is a helpful tool for this job, at best with blue light. Hens are quiet when roosting, and will not run away.

Note: Chickens get short of breath when carried upside down. Therefore, they should either be picked up one at a time as described above, or if they must be carried by the feet, this should not be done for more than a few steps or seconds. Chickens don’t have a midriff as we do, so their intestines fall into their ribcage when upside down, leading to problems breathing and potential suffocation.

Daily flock health observation

At the daily observation of the chickens for signs of illness, the observations should be performed in two steps. In a first step, the group or flock is observed from a distance, in a second step, individual birds are examined more closely.

Observation of the flock

Routine inspections include walking slowly through the flock and observing the chicks for any divergence in behaviour and visible health impairments. Another occasion for checking the behaviour of the animals is after fresh food and water have been provided. For this observation, one should stand still and relaxed at the side of the pen in order to not disturb, distract or frighten the chickens.

Because chickens are flocking animals, they will attempt to hide any weaknesses or disease symptoms and stay with the flock, if they feel threatened by human presence. If not frightened, they tend to explore everything new, which includes the observer, when entering the pen. Depending on the flock, it may take 5 to 10 minutes for them to relax or lose interest and display their natural behaviours. Patience is rewarded when one can see issues in the flock, and if any birds need to be more closely examined.

During routine inspections, one should always look for unfit birds in darker corners, the nests and on elevated perches, as sick chickens tend to withdraw from the flock.

During the day, healthy chicken should be:

- Eager to approach food and clean water and consume a constant amount of food and water.

- Showing natural behaviours such as scratching, dust bathing, preening.

- Alert to their environment.

- Breathing with a closed beak – unless it is very warm, when birds will breathe with a slightly open beak to cool off. This is also usually accompanied by slightly outstretched wings.

- Able to move freely without signs of limping or inability to stand.

- Free of obvious injuries (e. g. signs of feather pecking or blood).

- Growing at the proper rate for their age (pullets and broilers).

- Producing good quality eggs at the proper rate for their age (layers).

- Having the appropriate body weight for their age. All the animals of a flock should have similar weight.

Birds should not be:

- Unaware that fresh food and water are available or appear listless or unaware of their environment.

- Standing alone with fluffed feathers, retracted neck, and closed eyes.

- Sneezing or coughing.

- Breathing with an open beak (if not trying to cool down).

- Limping or unable to stand.

- Obviously injured (feathers or skin pecked, bloody).

Discussion on health observations

Discuss in groups what kinds of health observations the farmers have made. Ask them the following questions:

- What daily checks do you carry out in your flocks. If you do not perform any, would you now consider doing it? Why or why not?

- What kinds of symptoms have you observed with sick birds, and what did you do about them?

- Do you keep records of sick birds, symptoms, and any birds treated with antibiotics or other synthetic medications?

- Do you use any natural or other remedies you have found helpful?

- What are some major health challenges to your flock that you have not yet found a suitable solution for?

Inspection of individual birds

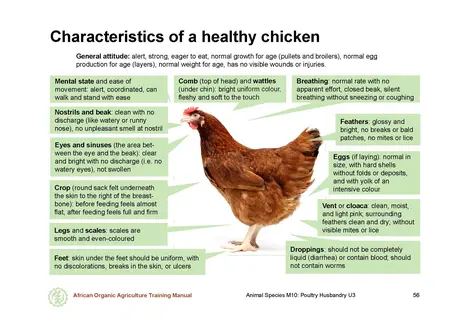

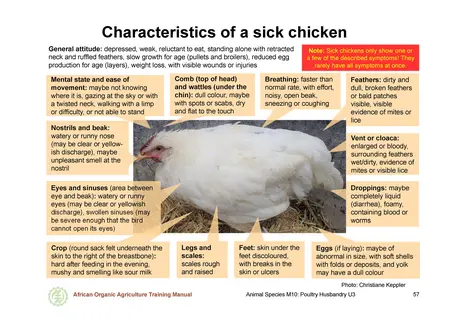

At least once a week, several chickens should be caught for a closer inspection. Additionally, if any signs of unhealthy birds are noticed during flock inspection, a closer examination of the affected birds is required. The inspected birds should be caught and handled with care to avoid further stress or injury. The observations should be noted on a piece of paper. The characteristics of a healthy and a sick bird are shown on the slides.

Body systems affected by disease

Diseases may affect one or several of a bird’s main body systems. The following is a brief introduction to those systems.

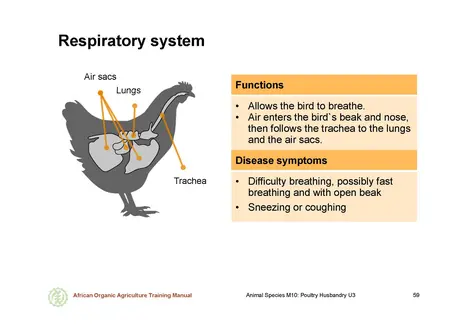

Respiratory system

This system allows the bird to breathe. The air enters the bird’s beak and nose, then follows the trachea to the lungs and to the air sacs.

When this system is affected, the bird will have difficulties breathing, may sneeze or cough, and may breathe rapidly and with an open beak.

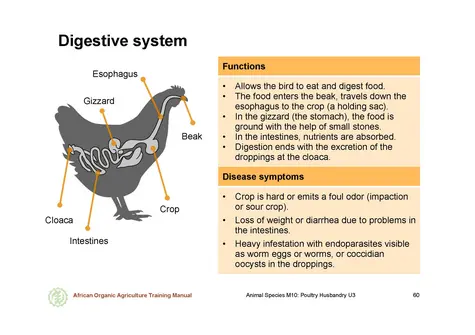

Digestive system

This system allows the bird to eat and digest food. Food enters the beak, travels down the oesophagus to the crop (a holding sac), is ground in the gizzard (the stomach) with the help of the gizzard stones, passes to the intestines for absorption of nutrients and water, and ends as droppings at the cloaca.

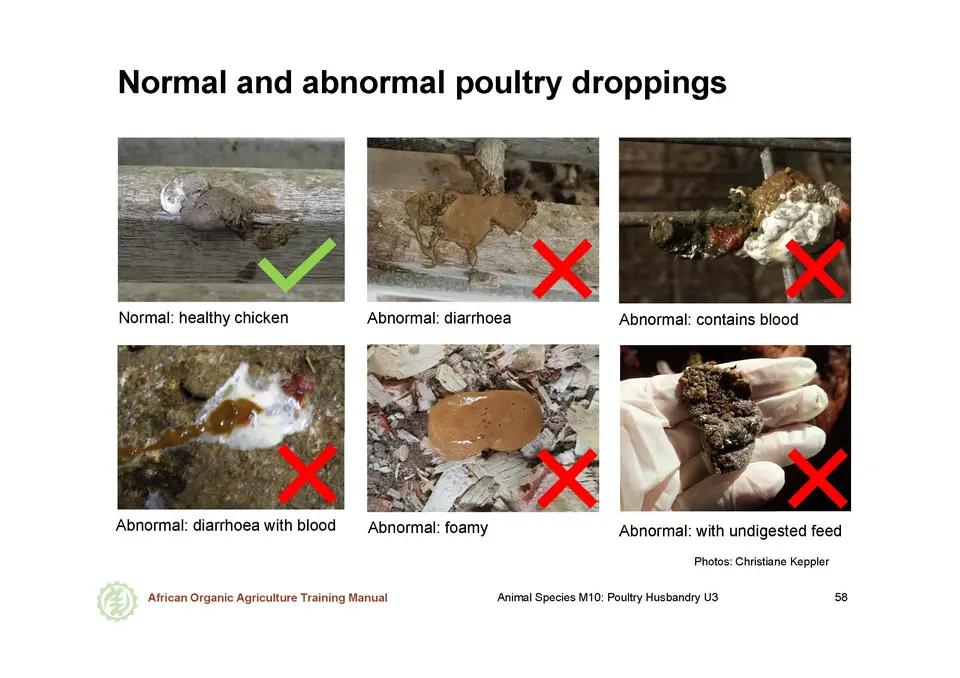

When this system is affected, there may be a crop problem where food becomes stuck and/or the crop is infected (impaction or sour crop), or the issue may be further down in the intestines. In this case, the bird may lose weight or have diarrhoea. The veterinarian or health worker may also detect too many worm eggs (or sometimes worms) or many coccidian oocysts in the droppings.

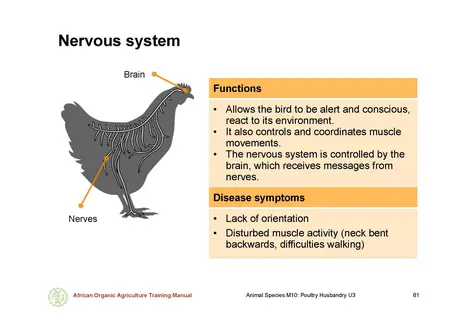

Nervous system

This system allows the bird to be alert and conscious, react to its environment, and it controls and coordinates muscle movement. It is controlled by the brain, which receives messages from nerves running throughout the body.

When this system is affected, the bird may appear to not know where it is, and muscle movement may be affected (either the neck is bent backwards, or the bird has trouble walking or cannot walk).

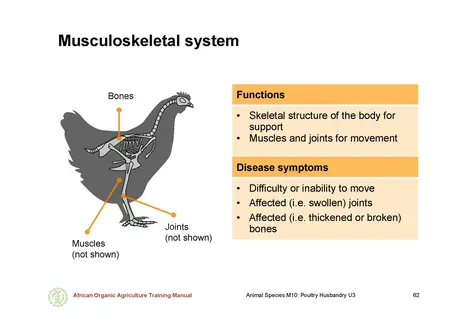

Musculoskeletal system

This system provides the bird’s body with its skeletal structure for support and muscles and joints for movement. When this system is affected, birds may have difficulty or be unable to move, may have affected joints (i. e. swollen) or have affected bones (i. e. thickened or broken).

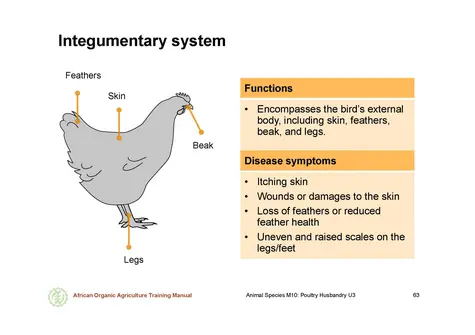

Integumentary system

This system encompasses the bird’s external body, including skin, feathers, beak, and legs.

When this system is affected, the bird’s skin may be itching or have wounds or show damages. The bird may lose feathers or have reduced feather health, or uneven and raised scales may be visible on the legs/feet.

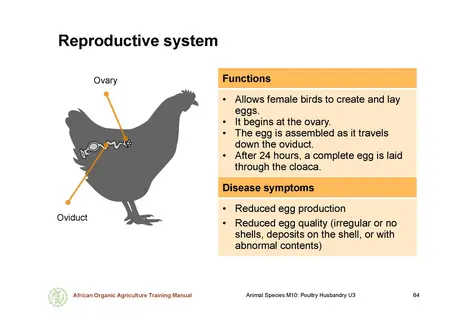

Reproductive system

This system allows female birds to create and lay eggs. It begins at the ovary, and the egg is assembled as it travels down the oviduct. After 24 hours, a complete egg is laid through the cloaca.

When this system is affected, egg production or egg quality may be reduced. Eggs may have irregular or no shells, deposits on the shell, or have abnormal contents inside.

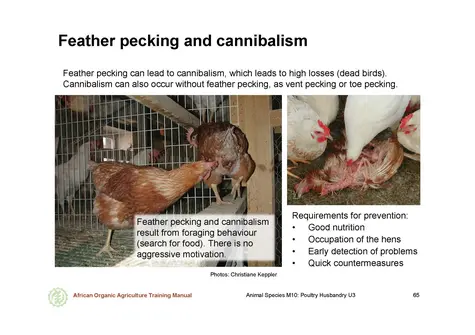

A note on feather pecking and cannibalism

Some injuries noted during the daily health inspection may not be caused by disease, but by the behaviour of the chickens themselves. It is important to also observe the behaviour of the chickens. If blood, missing or damaged feathers, or pecked dead birds are noticed, or if birds are observed that are pecking at each other or pulling out feathers from each other, these are indications of problems with feather pecking or cannibalism.

Some pecking is a normal behaviour of the chickens to establish hierarchies in the flocks. This type of pecking is directed to the other chickens’ heads and combs. Normal pecking should not cause serious injuries as long as the pecked chickens have enough space to evade.

In contrast, feather pecking and cannibalism are not related to establishing hierarchies, and because these behaviours can cause serious injury or death, they should be noted and prevented in the flock. Also, chickens learn these behaviours from others. This is why such behaviours must be quickly identified and stopped.

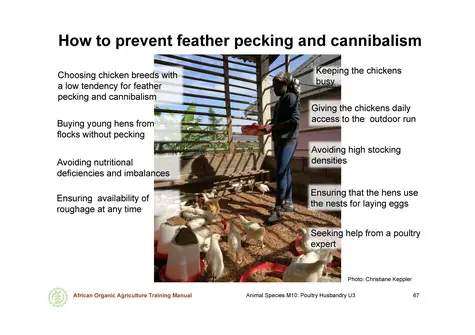

Recommendations for reducing feather pecking and cannibalism

- Choose chicken breeds with a low tendency for feather pecking and cannibalism. Often, more nervous or more active chickens also have a higher tendency for these unwanted behaviours.

- Unwanted behaviours like feather pecking and cannibalism can develop already at an early age (e. g. between 2 and 4 weeks of age). Once the chicks “learned” that behaviour, they tend to do it again whenever they feel stressed. Therefore, young hens should be bought from experienced poultry farmers with species-appropriate husbandry and feeding according to requirements of the growing up birds.

- Injurious pecking derives from searching for food. It can be a consequence of nutritional imbalances. Therefore, poultry farmers should ensure that the nutritional needs of the adult chickens are fulfilled.

- Pulling and eating of feathers can derive from a lack of roughage. Therefore, availability of roughage should be ensured at any time.

- Keeping the chickens busy distracts them from pecking each other. For example, one can spread grains into the litter and offer feed like carrots and fresh or dried plants (alfalfa or others) without shredding them first. Giving small portions each day instead of spreading too much food into the litter prevents mould.

- Feather pecking and injuries should be checked regularly. It is important to take measures against it as soon as pecking occurs. Chickens with bleeding wounds should be separated from the rest of the flock immediately. Even if the bleeding wound has not been caused by pecking, it tempts other chickens to peck at it.

- Unexperienced poultry farmers should start with low stocking densities, as the risk of cannibalism is much higher in flocks with high densities.

- Laying hens should be encouraged to use the nests. When laying an egg, the egg comes out of the cloaca and the cloaca is moist and shiny. If this happens outside the darker and secure nest, other hens might confuse the shiny cloaca with something edible and start to peck it.

- If the problem is already severe, a quick measure is the reduction of light. However, if hens are kept from pecking each other by dimming the light, they will usually start pecking again as soon as it is brighter again. Therefore, in severe cases, the problem is usually irreversible for that flock.

Common disease agents

In this chapter, different disease agents of poultry are presented, along with examples of the agents that are important in poultry farming. For each agent, it is explained what the disease is, how it enters the body, and how it causes disease. The importance in poultry health is described, and possible prevention and treatment methods are outlined. Then, zoonotic diseases are described that can pass from chickens to people.

The examples presented for each agent are listed in order of importance to poultry farming. Diseases that appear high on the list occur commonly, and can have high death rates in a flock. For example, among the viruses, Newcastle disease is listed first as it is currently the primary viral disease of concern in African poultry farming.

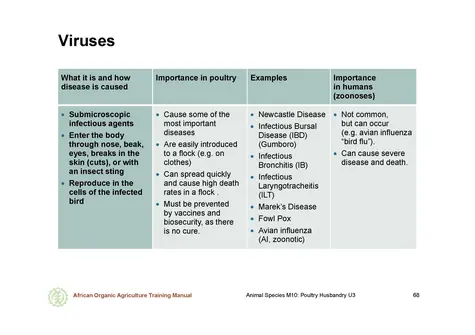

Viruses

Viruses are smaller than microscopic organisms. They can enter the body through the nose, the beak, the eyes, breaks in the skin (cuts), or be transferred with an insect sting. Inside the body, viruses reproduce in the cells, causing disease symptoms. Viruses are causing some of the most important diseases among poultry because:

- They can easily be brought into a poultry house (e. g. on the clothes of people coming from another poultry facility).

- They can spread quickly and cause high mortality (death) in a flock.

- They must be prevented by vaccines and biosecurity, as there normally is no cure against it.

- The major viruses that infect poultry are Newcastle Disease, Infectious Bursal Disease (IBD) (a.k.a. Gumboro), Infectious Bronchitis (IB), Infectious Laryngotracheitis (ILT), Marek’s Disease, Fowl Pox, and Avian influenza (AI, zoonotic).

- Although viral infections from birds to humans are not common, they can occur – for example with avian influenza caused by the virus H5N1, also called “Bird flu”. In humans “Bird flu” can cause severe disease and even lead to death.

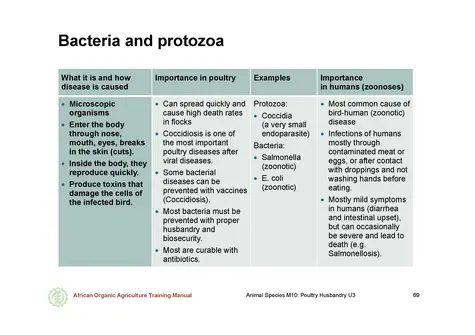

Bacteria and protozoa

Bacteria and protozoa are microscopic organisms that enter the body through similar routes as viruses. Once inside the body, they reproduce quickly, and release toxins that damage the cells of the infected bird, causing signs of disease.

Bacteria and protozoa are of next highest importance after viruses because:

- They can spread quickly and cause high mortality (death) in a flock (for example, coccidiosis is one of the most important poultry diseases after viral diseases)

- In some cases, they may be controlled by vaccines (Coccidiosis), but mostly, infections must be prevented by proper husbandry and biosecurity.

- Most bacterial infections are curable with antibiotics. However, antibiotics must be used strictly according to veterinary instructions to prevent resistances of the bacteria on a medium or long term. Some organic regulations define specific waiting periods after use of antibiotics, during which the products cannot be sold as organic.

- The most important examples of protozoa are coccidia (a very small endoparasite that can cause heavy losses in flocks, particularly in young animals). Examples of bacteria are salmonella and E. Coli. Both bacteria can be zoonotic, meaning that they can be transmitted to humans.

- Bacteria are the most common cause of disease transmitted to humans from birds. Humans are usually infected by eating contaminated poultry products like meat or eggs, or after contact with infected birds or droppings and not washing the hands before eating. Although the disease symptoms in humans are usually mild (diarrhoea and intestinal upset), the infections can occasionally become severe and lead to death (e. g. salmonellosis).

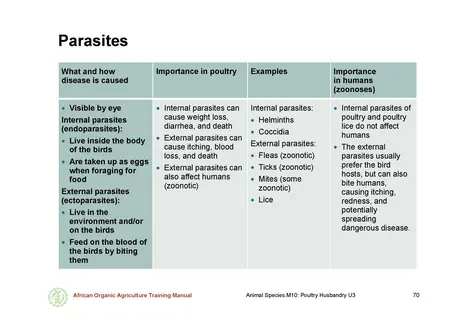

Parasites

Parasites can be detected without a microscope, but their eggs are microscopically small.

Internal parasites (endoparasites) live inside the body of the birds. The birds take them up as eggs when foraging for food. External parasites (ectoparasites) live in the environment and/or on the birds. They feed on the blood of the birds by biting them (fleas, ticks, red mites) or on the dead skin and feather cells (lice, mites).

Parasites are of the next highest importance after viruses and bacteria because:

- Internal parasites can cause weight loss, diarrhoea, and death.

- External parasites can cause itching, blood loss, and death.

- External parasites, although they usually prefer their bird hosts, can also affect humans (zoonotic diseases) causing itching, redness, and potentially spreading diseases. Internal parasites of poultry and poultry lice do not affect humans.

- Examples of internal parasites are Helminths and Coccidia. Examples of external parasites include fleas (zoonotic), ticks (zoonotic), mites (some zoonotic), and lice.

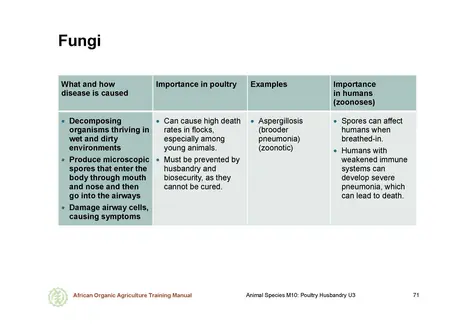

Fungi

Fungi are decomposing organisms that thrive in wet and dirty environments (i. e. like a dirty chicken house). They produce spores, which are microscopic particles that enter the body through the mouth and nose and then travel into the airway. There they damage airway cells, causing signs of disease.

These organisms are important because:

- They can cause high mortality (death) in a flock, especially when young animals are exposed.

- They must be prevented by husbandry and biosecurity, as there is no cure in case of infection.

- An example of a fungal disease is Aspergillosis (brooder pneumonia), a zoonotic disease. The spores of this fungus can affect humans that breathe them in, especially those with weakened immune systems. These people can develop severe pneumonia, which can lead to death.

Handling diseases in flocks

When animals with disease symptoms are noticed in a flock, the required actions may depend on the agent. However, it is always recommended to quarantine and examine affected birds more closely and to consult a veterinarian or extension worker if the cause of symptoms is not clear.

If animals do not eat properly, electrolytes, vitamins and minerals should be added to the drinking water to prevent dehydration. If the crop of a bird feels hard, one can gently massage it to break up the impacted roughage.

Viral diseases

Viral diseases cannot be treated. To avoid further distribution of the disease to other animals, immediate measures such as quarantine of diseased animals and disinfection of the poultry house must be taken together with the veterinarian. In case of viral infection, farmers should discuss a vaccination plan and review biosecurity procedures to prevent further spreading of the disease and future infections.

Bacterial diseases

Most bacterial diseases can be cured with antibiotics. For an effective treatment of a bacterial infection, the agent of the disease must be determined together with the veterinarian. The antibiotic is then prescribed by the veterinarian with indication of the dosage and the duration of the treatment.

Note: Antibiotics must be applied by the farmers as prescribed, because incorrect (too low) dosage and a too short treatment are the main reason for antibiotic resistance of bacteria! Also, the antibiotic substance should not be changed during an application cycle. In certified organic production, specific withdrawal guidelines may apply, and it may be necessary to keep records of the treatment.

Parasitic diseases

Parasitic diseases can be cured or prevented by vaccination in the case of coccidioses. If the purchased chicks are not vaccinated, farmers should discuss vaccination against coccidioses with the veterinarian.

Worms can be treated with anthelmintics that are administered during several days either in the feed or in the drinking water. As for other medicines, anthelmintics must be applied as prescribed to avoid development of resistance.

To prevent external parasites such as poultry red mites, common hygiene measures are most important. As soon as these mites are detected as small red spots in cracks of the poultry house or under perches, the inside of the house should be treated with diatomaceous earth. “Hot spots” with many mites can additionally be treated with ordinary household oil or with a natural acaricide (e. g. pyrethrum or Neem extract).

Fungi

Internal fungal infections cannot be treated, but the load of spores in the air can be reduced by increasing the air flow in the stable and making sure that the environment is dry. Fungi reproduce in wet material, so one should make sure to remove any wet litter and humid fodder residues. A disinfection and husbandry plan can be useful to prevent further fungal disease.

Nutrient deficiencies

Nutrient deficiencies that cause diseases can usually be treated, although some birds may suffer permanent effects. In case of deficiencies, the farmer and the veterinarian can review the feeding protocols to determine what elements might be missing or in excess (for more details, see chapter 4: “Feeding and drinking”).

Flock vaccination

Viral diseases and coccidiosis currently are the major threats to poultry production in Africa. Vaccines play a critical role in preventing and minimising these diseases. Which vaccines a farm requires depend on:

- the prevalent diseases in the area,

- the type of flock (broiler, layer, dual-purpose),

- the age and vaccine status of the birds upon arrival to the farm, as well as

- the cost, availability and storage capacities (many vaccines must be kept in a refrigerator to not lose their effectiveness), and

- the administration of the vaccines themselves,

Note: There is no “one fits all” vaccination plan for poultry. This is why each farm should develop its vaccine plan together with a local veterinarian or animal health worker both to maximise animal health and to stay within organic standards.

The following list is not a definitive vaccine schedule, but a list of vaccines to consider based on the factors mentioned above. It can be used as an aid in developing a vaccine plan with the veterinarian, and deciding where to purchase chicks (i. e. which vaccines are used at the hatchery).

All farms should buy vaccinated chicks/vaccinate against Newcastle disease and coccidiosis (if available).

Farms should buy vaccinated chicks/vaccinate based on disease prevalence in their region against:

- Marek’s Disease

- Infectious Bursal Disease (IBD) (Gumboro)

- Infectious Bronchitis (IB)

- Infectious Laryngotracheitis (ILT)

- Avian influenza (AI) (zoonosis)

- Direct and indirect administration of vaccines

There are two ways for the administration of vaccines: direct and indirect administration.

Direct administration can be done by injection of a vaccine with a needle or in liquid form into the beak or eye of the animal. This method ensures that each chicken receives the vaccine, but creates high labour costs as each chicken must be handled individually, and can cause injuries in the chickens if done by untrained staff.

Indirect administration can be done, either by exposing the chickens to a vaccine that is dissolved in their drinking water or sprayed in the air/onto the flock. Indirect administration involves low labour costs, but sometimes results in too low vaccination rates, which means the flock is still vulnerable to a disease outbreak.

Timing of vaccinations

Some vaccinations are best applied in the hatchery, because many diseases can affect chicks at a very early age. It is also better to deliver chicks that already have some immunity when they are transferred to the farm.

Some vaccines are only available in larger quantities and/or degrade within hours after opening. Therefore, it makes sense and is more economical to vaccinate large numbers of animals in the hatchery rather than wasting vaccines when vaccinating small numbers of animals on farms.

Some vaccines, however, lose power (efficacy) as chicks grow, and need to be administered again. Repeated administrations of vaccines are called “booster” vaccinations. They must be administered on a specific schedule to young chickens and yearly for mature chickens in order to maintain their effectiveness.

Some vaccines must be given to mother hens at the correct time so that disease immunity (protection) is passed from the mother hen to her eggs.

Because there is no “one size fits all” vaccination plan for poultry, each farm should develop its vaccine plan together with a local veterinarian or animal health worker both to maximise animal health and to comply with the organic standards.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.