Health

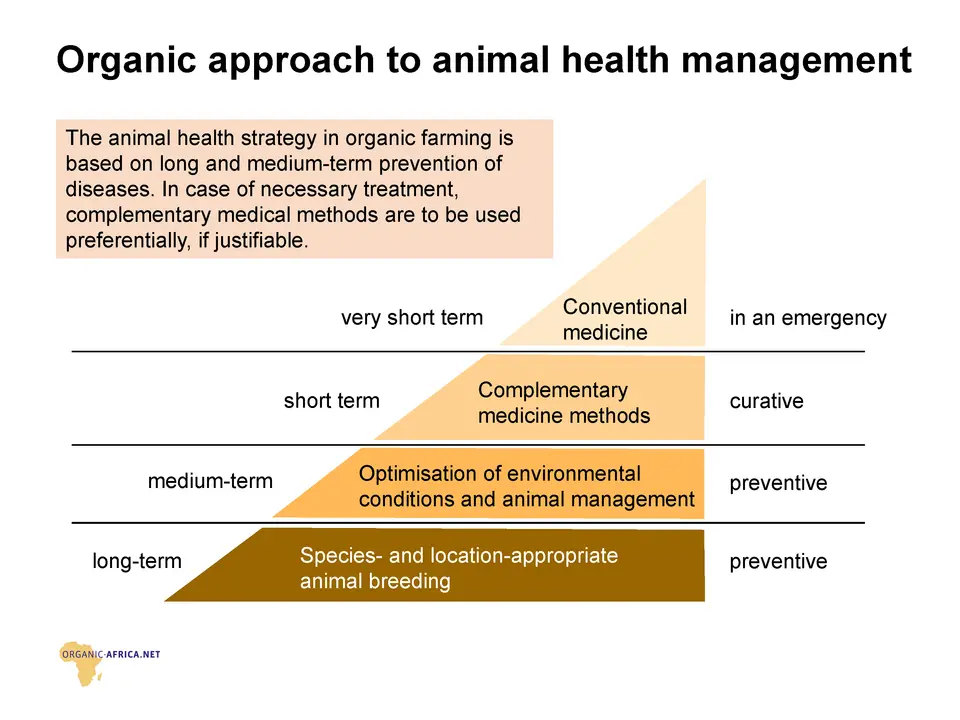

Disease prevention as a first step and key principle

A note on access to veterinary care : This chapter is intended to be a supplement to care of animals by a veterinarian or local animal health worker. Therefore, the chapter cannot be read as a comprehensive “how to” guide in diagnosing or treating animals. It is, however, an orientation to how animal health is seen in organic agriculture, which may be useful to bring to the attention of the veterinarian, who may have not had specific training in dealing with organic regulations. Ensuring access to veterinary care should ideally be a prerequisite before acquiring or expanding a herd of cattle or other livestock.

Maintenance of health in organic cattle farming primarily relies on the long and medium-term prevention of diseases and health problems. Prevention includes avoidance of infections by pests and diseases, optimising the animals’ environment and nutrition, minimising stress, and selecting the appropriate genetics. Besides being a cornerstone of organic farming, disease and pest prevention ensures both human and animal safety, animal welfare, higher animal productivity, and ultimately better profits for farmers.

Preventing diseases in cattle also helps to prevent the spread of zoonotic diseases (diseases spreading from animals to people or vice versa). Zoonotic diseases include diseases like salmonella, a bacterium that can be found in raw milk or cattle faeces. The bacterium usually causes no symptoms in the animals, however, in humans, salmonellosis (the most common cause of ’food poisoning‘) causes diarrhoea and fever, and sometimes more severe symptoms. Therefore, prevention of diseases helps to keep the animals, the farmers and the community safe.

Disease and pest prevention also contribute to the prevention of pain, lameness, and premature death. Prevention not only is an expression of respect for the animals and the goods and services they provide, but also has practical aspects. While disease prevention may require time for herd observation and early treatment, it saves considerable time and costs in the long run.

In the event of an illness in a herd, quick action is required to avoid further illness and spreading. Sick animals should be separated from the herd and checked for further symptoms. If available, a veterinarian, community animal health worker or neighbour knowledgeable in cattle health should be contacted in the case of an unknown or more severe disease that cannot be cured by the farmer himself/herself.

Proper diagnosis of the disease is crucial for effective treatment. Where herbal medications (phytomedicines) are not available or not effective enough, synthetic medications should be used to avoid suffering of the animals and further illness. In case of diagnosis of a non-curable and/or highly infectious disease, animals may have to be culled and if infectious all the premises must be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected. Such incidents are stressful, time-consuming and costly.

Conscientious prevention also reduces the need for antibiotics. While the prophylactic use of antibiotics and other conventional medication is not allowed in certified organic production, their curative use is permitted when natural remedies do not have the required efficiency. However, it is important to note that the use of antibiotics also has a number of adverse effects. In case of over-use, antibiotics cause a selection of resistant bacteria. As a result, over time, antibiotics become less effective, or even ineffective, especially if the antibiotics were not applied properly. It is therefore crucial to follow the directions of the prescribing veterinarian when treating with antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is increasing worldwide, both in animals and humans, and is becoming a problem in human health management. The best prevention of antibiotic resistance on a farm is to minimise the use of antibiotics by implementing proper prevention measures and management against diseases.

Disease prevention

Good disease prevention is the key to a healthy and productive herd. Diseases are prevented by a holistic approach to animal welfare, which not only focuses on how to keep diseases and health issues away but how to maintain health. The pillars of herd disease prevention are:

- Breeding for good health and productivity (Chapter Breeding)

- Demand-based, species-appropriate nutrition and sufficient clean water at all times (Chapters Feeding)

- Minimal stress

- Housing with good ventilation, sufficient space, and an outdoor area allowing natural behaviour (Chapter Housing)

- Robust cleaning procedures that ensure a clean and dry environment (Chapter Biosecurity measures)

- Biosecurity measures to minimise entry and spreading of diseases on the farm (Chapter Biosecurity measures)

- Quick identification of problems and appropriate action (Chapter Herd and animal observations and Ration formulation)

- Appropriate vaccination program (Chapter Vaccination, deworming and pest prevention)

- Regular claw care (Chapter Claw care)

- Appropriate deworming program (Chapter Vaccination, deworming and pest prevention)

- Pest treatments program (Chapter Vaccination, deworming and pest prevention)

- Low stress animal management (Chapter Low stress animal management)

- Daily herd and individual animal observations (Chapter Herd and animal observation)

Biosecurity measures

Biosecurity measures aim to prevent diseases from entering the farm, and from spreading within the farm. While biosecurity measures may vary for each farm, it is important to understand how diseases can enter and spread on the farm:

- In or on new purchased animals

- On hands, shoes, clothing or vehicles of visitors that have been in contact with sick or infected animals

- On hands, shoes, clothing or the vehicle of a veterinarian or animal health worker that has been in contact with sick or infected animals

- In or on wild animals, neighbouring livestock, or other wild or domestic animals (i. e. cats, dogs, mice) that have been in contact with or fed on sick or infected animals and interact with the herd

- On hands, shoes, clothing or equipment used by the farmer as he/she travels between pens or animals

- In feed or feed components bought in or stored on the farm under unhygienic conditions

- Via biting insects, mites or ticks that have bitten sick or infected animals

Because diseases caused by viruses, bacteria and parasites can easily enter a farm in various ways, these are often undetected. Nevertheless, each farm should have a plan in place to minimise the entry of diseases. While it may not be practical or possible to implement all measures on a farm, farmers should try to implement as many biosecurity measures as possible.

General biosecurity recommendations

Although these recommendations may differ depending on the operation, the following can be considered good practice for most herds.

- Secure sources of supply: Only buy healthy animals. Animals should be purchased from a farm with good management, hygiene and vaccination practices when possible.

- Observing the herd daily for signs of disease allows for rapid detection and ide-ally allows the farmer to quickly quarantine sick animals, consult a veterinarian or community animal health worker, diagnose, and treat the disease with natural remedies before it be-comes severe and before synthetic drugs such as antibiotics are required.

- Quarantine pen/separate area for new animals: If new animals are brought onto the farm, they should be placed in a quarantine pen or separate area for 30 days for monitoring to avoid spreading diseases to the current herd. This pen or area can also be used to separate sick or injured animals for treatment.

If possible and depending on setup of the farm, the following may also help to reduce the incidences of disease:

General cleanliness/keeping yourself healthy and minimising disease transfer on the farm

- Washing stations: Hand washing stations with water and soap should be available near the animals so hand washing can be done frequently and after any contact with dirty materials.

Keeping extra people and animals out of the farm

- Perimeter fence: If practical and appropriate, a perimeter fence can minimize unwanted animals and people on the farm.

- Sales area outside the farm: If sales of milk, meat, or other products are done directly from the farm, the sales area should be set up outside the perimeter fence of the farm. This reduces the risk of disease entry via the clothing, boots and hands of visitors.

Removing/sanitizing dirty material

- Cleaning of all equipment used outside the farm: If sales are done from a market, all equipment (i. e. milk bottles, containers, etc.) need to be thoroughly cleaned, disinfected, and dried before entering the ’clean‘ part of the farm.

- Composting: Used bedding, droppings and the unmarketable parts of healthy animals from slaughter can be composted and turned into a valuable fertilizer for crops. Care needs to be taken that wild animals and other predators and scavengers are excluded from the compost pile, as they can transmit undetected diseases.

- Establishment of a burn pile: The establishment of a burn pile far enough from the main house or barn facility that the smoke will not blow in allows a farmer to dispose of animals who have died of disease and of contaminated bedding from those animals to avoid disease spread. Burying a large animal such as a cow or bull is not recommended, as residues can leach into the surrounding ground water and contaminate it.

Low stress animal management

Cattle are herd animals that can be easily stressed when handled if they are not accustomed to it. Therefore, good handling practices and facilities are helpful in ensuring animal welfare and health. Animals should be treated calmly, and are most comfortable when they understand a daily routine. Cattle will be easiest to handle when they are handled frequently from a young age. To avoid issues with catching or tying animals, start to practice these practices when they are calves to prevent issues when they are older and larger. Calves will quickly learn to accept a rope halter, and will happily stand when they are being fed. Grooming the animals is another way to increase their comfort around people. Animals that are gentle and easy to approach are safer to work around, and are much easier to manage when they are sick or injured. With the introduction of good practices (basics of low-stress cattle handling practices), the use of cattle prods or other painful techniques should not be necessary.

Watch the following introduction video about “Low-Stress Stockmanship with Cattle” with English subtitles: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=04esfEMQh1k

Herd and animal observations

The daily observation of cattle for signs of illness should be performed in two steps. In a first step, observe animals from a distance, in a second step, individual animals are examined more closely.

Herd observations: Daily inspections include observations of the herd by standing still in a distance of 10 meters to the herd. Depending on whether the animals are used to people and whether they are young animals or bulls, more distance is recommended. One should have a good overview over all animals and the surroundings. The observer should not walk through the herd, but stand next to it. Because cattle are herd animals, they will attempt to hide any weaknesses or disease symptoms and stay with the group if they feel threatened by a human presence. Depending on the herd, it may take 5 to 10 minutes for them to relax or lose interest and display their natural behaviours. Patience is rewarded with detecting health issues at an early stage when any animals need to be more closely examined.

Signs of a healthy herd

- Are eager to approach food and clean water and consume a constant amount of food and water.

- Are ruminating and chewing their cud after eating

- Are alert to their environment

- Are free of obvious injuries and able to move with no impediments (e.g. no limping)

- Are free of obvious signs of disease such as breathing with an open mouth, sneezing or coughing, discharge from the eyes or nose, hair loss, or itching

- Have healthy skin, coat, and claws

- Are growing at a constant rate and have good body condition

- Are producing good quality and quantity of milk (dairy animals)

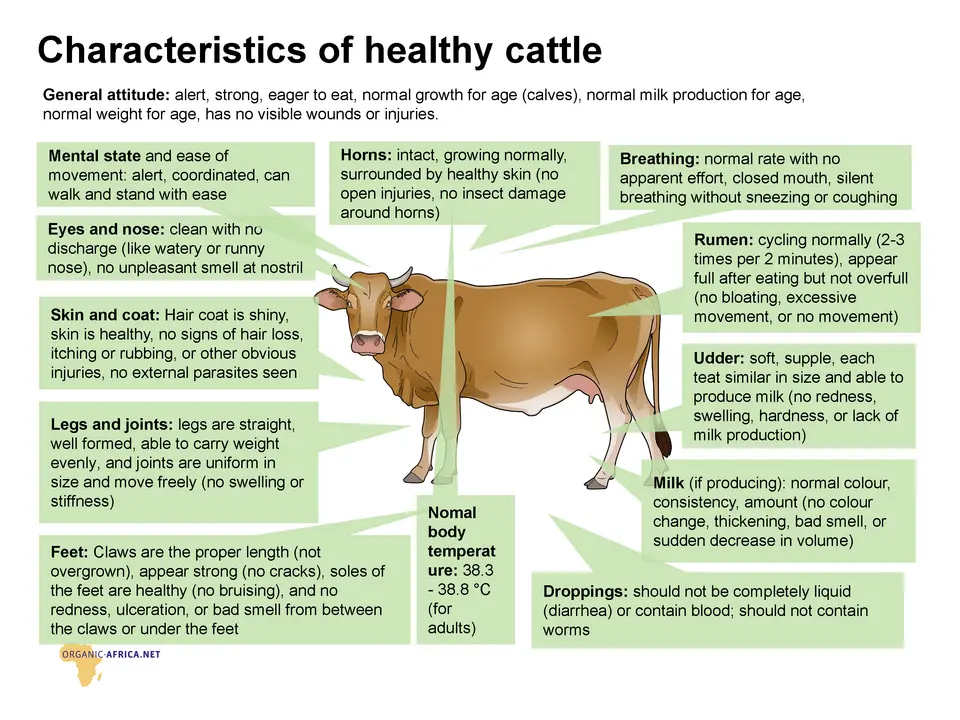

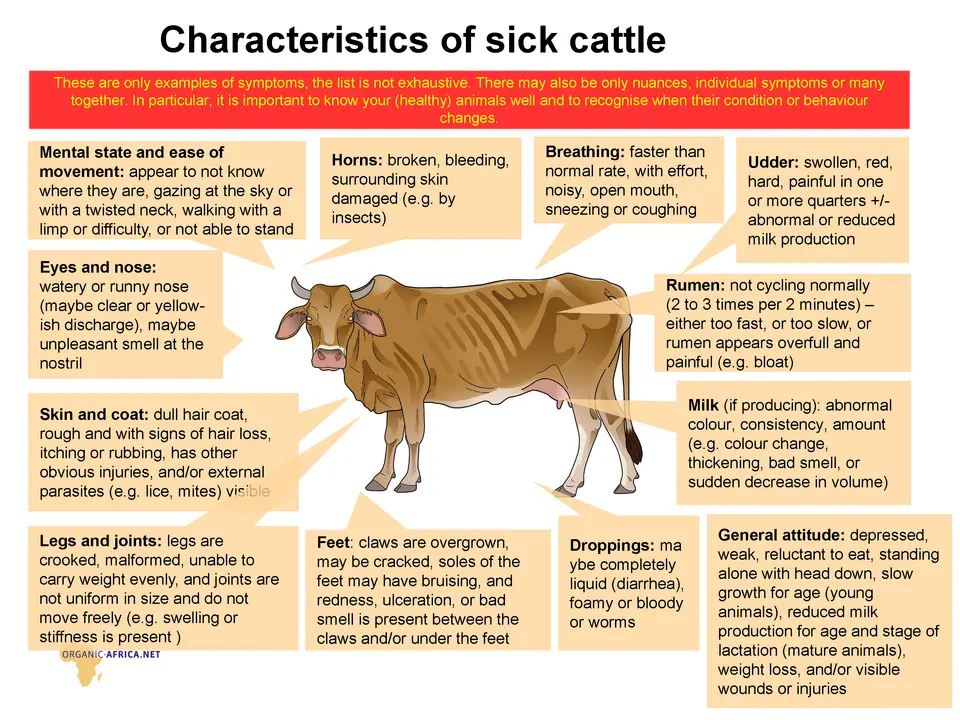

Individual animal observations: The following illustrations show signs of healthy and sick animals. In the beginning, it makes sense to check all the symptoms of the animals one by one. In time, however, one will be trained to notice them immediately, for example, when cleaning the barn in a dairy herd or walking by a beef herd. One should always look at the animals from the claws to the tail end to the tip of the nose and from different sides. For observation, the animals should be clean so that wounds are not covered by dirty fur and become unnoticeable.

Characteristics of a healthy cow:

When an animal shows symptoms of illness, one should act depending on the symptom and severity. This can include:

- Separate animal and provide it with feed and clean water

- Call a veterinarian or animal health worker to achieve the proper diagnosis.

- Quarantine the diseased animal.

- Stop bleeding and disinfect wounds.

- If animals do not eat properly, electrolytes, vitamins and minerals should be added to the drinking water to prevent dehydration.

- Treat according to the specific diagnosis.

Vaccination, deworming and pest prevention

Vaccinations

Viral and bacterial diseases are currently the major threats to cattle production in Africa. Vaccines play a critical role in preventing and minimising these diseases. Which vaccines a farm requires depend on:

- the prevalent diseases in the area,

- the type of herd (beef, dairy, mixed)

- the cost, availability and storage capacities (many vaccines must be kept in a refrigerator to not lose their effectiveness), and

- the administration of the vaccines themselves,

Note: There is no “one fits all” vaccination plan for African livestock farmers. This is why each farm should develop a vaccine plan together with a local veterinarian or animal health worker, both to maximise animal health and to stay within organic standards. The following list is not a definitive vaccine schedule, but a list of vaccines to consider based on the factors mentioned above. It can be used as an aid in developing a vaccine plan with the veterinarian.

Important diseases that should be considered when designing a vaccine plan depending on herd type, location, disease prevalence, etc:

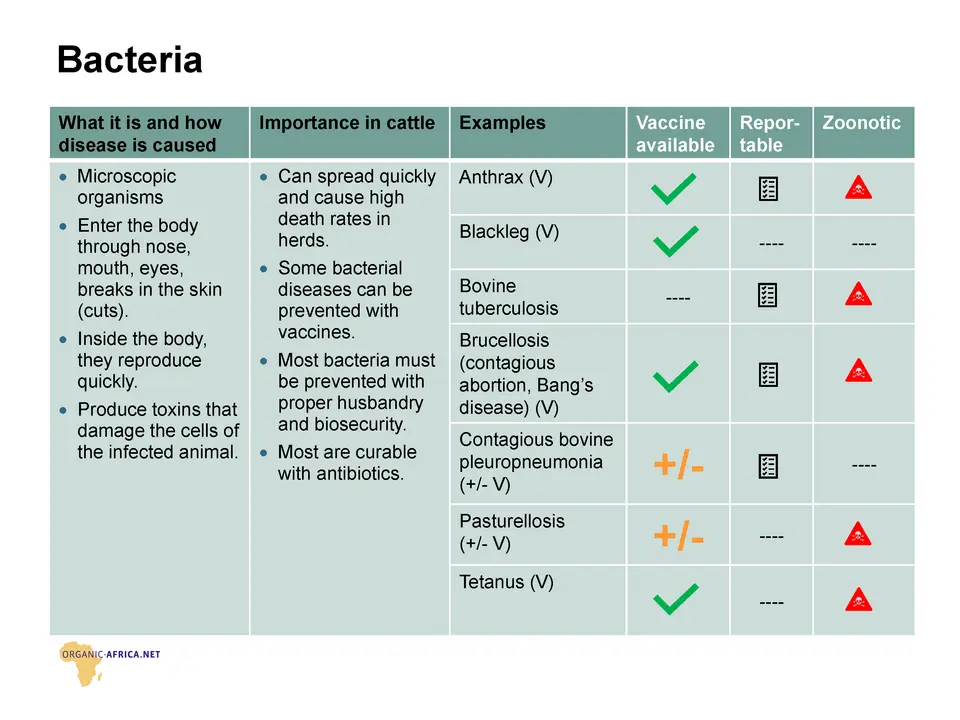

Bacterial

- Anthrax

- Blackleg

- Brucellosis (contagious abortion, Bang’s disease)

- Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia

- Lumpy skin disease

- Pasturellosis

- Tetanus

- Botulism

Viral

- Bluetongue

- Rabies

- Rift Valley Fever

Protozoal

- East Coast Fever (ECF)

- Trypanosomiasis

These diseases are covered in more detail in the following sections, along with symptoms and treatment options (viral, bacterial, protozoal).

An important note for organic producers

For the diseases and ailments of cattle, the first step in agroecological/organic production is prevention. Therefore, each of these sections will detail preventive measures where available. The next step is natural remedies. Using synthetic drugs and other chemicals should only be considered where preventive measures and natural remedies have failed.

Therefore, the medication types listed in the following sections should be used only when other steps have not been effective. Additionally, all commercially available drugs and chemicals are subject to organic guidelines. It is important to work with a veterinarian who is familiar with organic regulations to avoid problems. If this is not available, an organic producer group can give advice and guidance that can be used with veterinary advice to keep animals healthy while maintaining organic standards.

Infectious diseases

In this section, different infectious disease agents of cattle are presented, along with examples of the agents that are important in cattle farming. For each agent, it is explained what the disease is, how it enters the body, and how it causes disease. The importance in cattle health is described, and possible prevention and treatment methods are outlined.

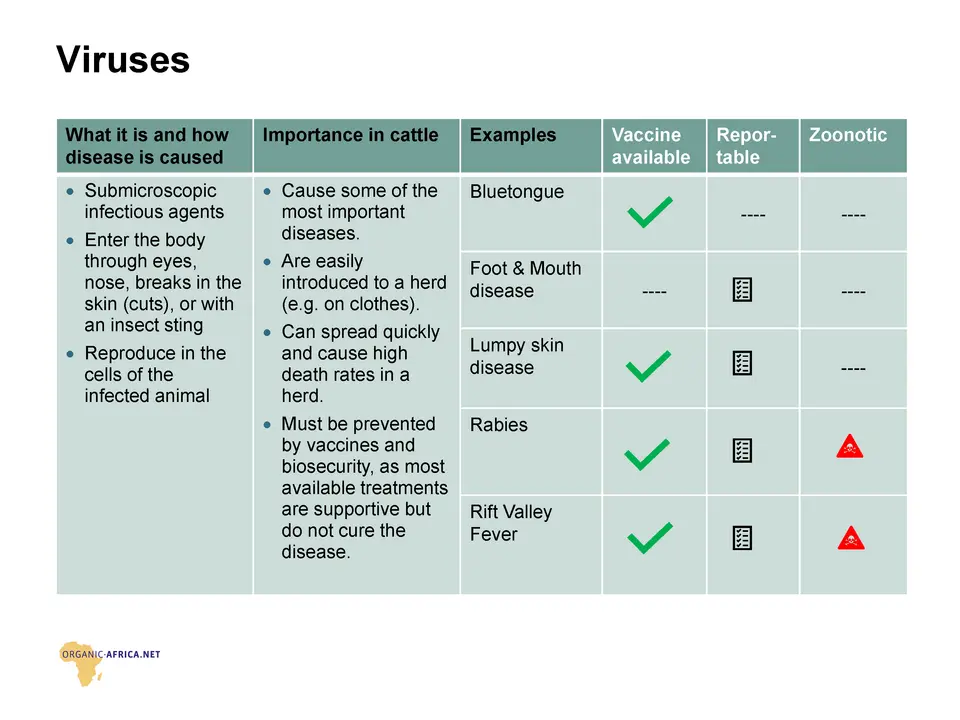

Viral diseases

Viruses are smaller than microscopic organisms. They can enter the body through the nose, the beak, the eyes, lesions in the skin (cuts), or be transferred with an insect sting. Inside the body, viruses reproduce in the cells, causing disease symptoms. Viruses cause some of the most important cattle diseases because:

- They can spread easily (e. g. on the clothes of people coming from another farm or via wild or other animals).

- They can spread quickly and cause high mortality (death) in a herd.

- They must be prevented by vaccines and biosecurity, as there normally is no cure for viral diseases, if the animal’s immune system is not able to fight the disease.

Treatment: The best protection against viral diseases is prevention, i.e. a strong, well-fed animal with an intact immune system. However, if a viral disease does occur, to avoid further distribution of the disease to other animals, immediate measures such as quarantine of diseased animals and disinfection of the area where the animals are kept must be taken together with the veterinarian. In case of viral infection, farmers should discuss a vaccination plan and review biosecurity procedures to prevent further spreading of the disease and future infections.

The major viral diseases in cattle in Africa are:

- Bluetongue (V = means vaccination is available)

- Foot and mouth disease

- Lumpy skin disease (V)

- Rabies (V)

- Rift Valley Fever (V)

Bluetongue: The virus causing bluetongue disease is spread by a small biting insect (midge). Affected cattle may have a fever, breathe more quickly, drool, or develop lesions on the skin or in the mouth. Pregnant cattle may abort. Depending on the strain of the virus, mortality (death) is generally low (from 2 to 30 %), but can be as high as 70%. Vaccination is the best prevention against this disease.

Foot and mouth disease: Foot and mouth disease is generally spread through the air when cattle breathe in the virus from another infected animal. Foot and Mouth disease is spread between bovines, so this includes wild animals such as buffalos. However, all parts of an animal that is infected with the disease can spread the disease (e.g. milk, meat), and the virus can live on contaminated surfaces and materials. Affected mature cattle usually develop a fever and lose their appetite, and shortly thereafter develop the characteristic “blisters” (vesicles) of the disease in their mouths, teats, and between their claws. Generally, mortality is low in mature animals, but may be high in younger animals. Infected animals that recover generally become carriers, thus able to spread the disease for long periods of time (years). Surveillance, identification, and quarantine of affected herds are the best preventions against this disease. Unfortunately, since the virus has many ’types‘ (variants), specific vaccines need to be developed for each one. Because there are many ’types‘ present on the African continent, there are generally no widely available vaccines.

Important note: This disease is ’reportable‘, meaning that if one suspects the presence of this disease in the herd, one must immediately report it to a public health veterinarian in the area. They will then advise the holder on how to proceed to avoid further spread of the disease to other animals or herds.

Lumpy skin disease: The virus that causes lumpy skin disease is spread through the bite of ticks and insects. Affected animals generally have a fever, watery eyes, and characteristic small ’lumps‘ under the skin that are painful. Most animals recover, but productivity is lost when animals lose weight due to the disease, have reduced milk volumes, and have hides that are damaged and cannot later be sold. Prevention of the disease involves buying animals from herds that are known to be free of the disease, and keeping the animals separate from herds which may be infected. Vaccination is the best prevention against this disease, although unfortunately the vaccines are not universally available in Africa.

Rabies: Rabies is spread through the infected saliva of another animal. Cattle may become infected when they are bitten by another infected mammal (e.g. a stray dog, or a wild animal such as a bat, fox, etc.). Symptoms may vary from an animal that simply stands and seems unaware of its environment, to an animal that is itching, unusually aggressive, drooling, and appearing to choke. Rabies is always deadly (fatal), and infected animals generally die within 4 to 5 days of becoming infected. Keeping cattle away from feral dogs that may be infected is one prevention strategy. Vaccination is the best prevention against this disease, although it is not routinely done in cattle. Most rabies prevention programs focus on vaccinating local dogs.

Important note: Rabies is a zoonotic disease, meaning that this virus can also infect people. If a person is infected, the disease is almost always fatal. If one suspects an animal has rabies, one should not approach it, touch it, or come into contact with any bodily fluids. Instead, one should call a veterinarian or public health official immediately for help. If one has been exposed, one should wash the area thoroughly with soap and water and seek medical attention immediately.

This disease is also ’reportable‘, and a public health veterinarian should be notified immediately if suspected.

Rift Valley Fever: Rift Valley Fever is spread through the bite of a mosquito. Older animals may have a fever, runny nose, weakness, and pregnant animals may abort. Generally, mortality (death) is low in older animals but higher in younger animals, who may develop a fever, weakness, diarrhea, and die within a few days of infection. Because the disease is linked to mosquitoes, it generally appears as large ’outbreaks‘ every 5 to 10 years. Therefore, although vaccination is the best prevention against this disease, it is hard to convince farmers to vaccinate against a disease that is only occasionally present.

Important note: Rift Valley Fever is a zoonotic disease, meaning that this virus can also infect people. Symptoms in humans range from flu-like symptoms to occasional death in severe cases. If an animal is suspected to have Rift Valley Fever, one should not approach it, touch it, or come into contact with any bodily fluids. Instead, a veterinarian or public health official should be called immediately for help. If a person has been exposed, medical attention must be sought immediately.

This disease is also ’reportable‘, and a public health veterinarian should be notified immediately if suspected.

Bacterial diseases

Bacteria are microscopic organisms that enter the body through similar routes as viruses. Once inside the body, they reproduce quickly, and release toxins that damage the cells of the infected animal, causing signs of disease. Bacteria are of next highest importance after viruses because:

- They can spread quickly and cause high mortality (death) in a herd (for example, bacterial respiratory infections are one of the most important cattle diseases after viral diseases)

- In some cases, they may be controlled by vaccines, but mostly, infections must be prevented by proper husbandry and biosecurity.

- Most bacterial infections are curable with antibiotics. However, antibiotics must be used strictly according to veterinary instructions to prevent resistance of the bacteria on a medium or long term. Usually, organic regulations define specific waiting periods after use of antibiotics, during which the products cannot be sold as organic.

- Bacteria are the most common cause of disease transmitted to humans from cattle. Humans are usually infected by eating contaminated products like milk or meat, or in more rare cases after contact with infected animals or droppings. Although the disease symptoms in humans are usually mild (diarrhea and intestinal upset), the infections can occasionally become severe and lead to death (e. g. salmonellosis).

Treatment: Most bacterial diseases can be cured with antibiotics. For an effective treatment of a bacterial infection, the agent of the disease must be identified together with the veterinarian. The applicable antibiotic is then prescribed by the veterinarian with indication of the dosage and the duration of the treatment.

Correct use of antibiotics

Antibiotics must be applied by the farmers as prescribed, because incorrect (too low) dosage and a too short treatment are the main reason for antibiotic resistance of bacteria, which will cause them to rest antibiotic treatment in the future, leading to non-treatable bacterial infections! Also, the antibiotic substance should not be changed during an application cycle. In certified organic production, specific withdrawal guidelines may apply, and it may be necessary to keep records of the treatment.

The major bacterial diseases in cattle in Africa are:

- Anthrax (Vaccine available)

- Blackleg (Vaccine available)

- Bovine tuberculosis (Zoonotic)

- Brucellosis (contagious abortion, Bang’s disease) (Vaccine available)(Zoonotic)

- Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (+/- V)

- Pasturellosis (+/- V)

- Tetanus (V)

Anthrax: Anthrax is present in the soil, and animals become infected when they breathe in or eat the spores. The first sign of anthrax is generally the sudden death of animals without other signs. In areas where anthrax is a problem, vaccination is the best prevention against this disease.

Important note: Anthrax is a zoonotic disease, meaning that this virus can also infect people. Symptoms in humans range from flu-like symptoms to death in severe cases. If one suspects an animal to have anthrax, one should not approach it, touch it, or come into contact with any bodily fluids. Instead, a veterinarian or public health official should be called immediately for help. If one has been exposed, one should seek medical attention immediately.

Blackleg: Similar to anthrax, the bacteria that causes blackleg is found in the soil, and animals become infected when dirt enters a wound, or if it is eaten. The first sign of blackleg is generally the sudden death of animals without other signs. Some animals may be lame before death, and after death there is generally swelling and gas trapped under the skin. In areas where blackleg is a problem, vaccination is the best prevention against this disease.

Bovine Tuberculosis: The bacteria causing bovine tuberculosis is spread by the air when an infected animal breathes or coughs. Calves can be infected by drinking the milk from an infected mother. Most animals do not die from this disease, rather they are affected over the long term with periods of fever, cough, weight loss, and large lymph nodes, this will lead to a severe reduction in productivity. Prevention of the disease involves buying animals from herds that are known to be free of the disease, and keeping the animals separate from herds who may be infected. Unfortunately, there are no widely available vaccines for this disease.

Important note: Bovine tuberculosis is a zoonotic disease, meaning that this virus can also infect people. Symptoms in humans range from flu-like symptoms to death in severe cases. If one suspects an animal to have bovine tuberculosis, one should not approach it, touch it, or come into contact with any bodily fluids. Instead, a veterinarian or public health official should be called immediately for help. If one has been exposed, one should sought medical attention immediately.

This disease is also ’reportable‘, and a public health veterinarian should be notified immediately if suspected.

Brucellosis: The bacteria that causes brucellosis is spread when animals come into contact with the fluids from an infected female animal either in her reproductive tract (when breeding), in an aborted fetus, or in the placenta/fluids after birth. Adult animals do not normally show symptoms, but the disease causes heavy losses in herds due to abortions, low fertility, and reduced milk production. Prevention of the disease involves buying animals from herds that are known to be free of the disease, and keeping the animals separate from herds who may be infected. Vaccination is the best prevention for this disease.

Important note: Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease, meaning that this virus can also infect people. Symptoms in humans range from flu-like symptoms to death in severe cases. If one suspects an animal to have brucellosis, one should not approach it, touch it, or come into contact with any bodily fluids. Instead, one should call a veterinarian or public health official immediately for help. If one has been exposed, one should seek medical attention immediately.

This disease is also ’reportable‘, and a public health veterinarian should be notified immediately if suspected.

Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia: The bacteria causing contagious bovine pleuropneumonia is spread in the air when an infected animal breathes or coughs. Signs include fever, coughing, and weakness. Mortality (death) in an exposed herd can reach 50 %. Animals that recover may have chronic lung problems. Prevention of the disease involves buying animals from herds that are known to be free of the disease, and keeping the animals separate from herds who may be infected. A vaccine is available, but it is only effective when there are high rates of vaccination within a country.

Important note: This disease is ’reportable‘, and a public health veterinarian should be notified immediately if suspected.

Pasturellosis: The bacteria that causes pasturellosis is spread in the air when an infected animal breathes or coughs, in their saliva, or when other animals eat and drink food and water that has been contaminated by an infected animal. Young animals are generally affected when they are stressed (e.g. are shipped to a new location). Signs include fever, weakness, rapid breathing, and discharge from the nose. Most animals recover, although they may grow more slowly, and some may remain permanently small and unhealthy. The best prevention against this disease is to avoid stressing young calves and avoid mixing them with many other animals from different herds. There are vaccines available if the preventive measures are not possible.

Important note: Pasturellosis is a zoonotic disease, meaning that this bacterium can also infect people. Symptoms in humans are generally an infection in the skin where the bacteria entered, but if the disease enters the bloodstream it can cause severe disease and death. If one suspects an animal to have pasturellosis, one should not approach it, touch it, or come into contact with any bodily fluids. Instead, one should call a veterinarian or public health official immediately for help. If one has been exposed, one shouldseek medical attention immediately.

Tetanus: The bacterium that causes tetanus, similar to anthrax and blackleg, is found in the soil (as well as in dust and manure), and generally enters the body through wounds. Symptoms include stiffness, bloat, collapse, and death. Prevention includes doing any medical procedures that may leave an open wound (e.g. castration) in a clean area, with clean and disinfected tools. One should ensure that calving also takes place in clean areas. In locations where tetanus is a problem, vaccination is the best prevention against the disease.

Important note: While tetanus is not contagious from animals to people, if it is present in the environment, it can also enter the human body through small wounds (e.g. a small cut on a finger or foot). Vaccination is the best protection against this disease in humans, too.

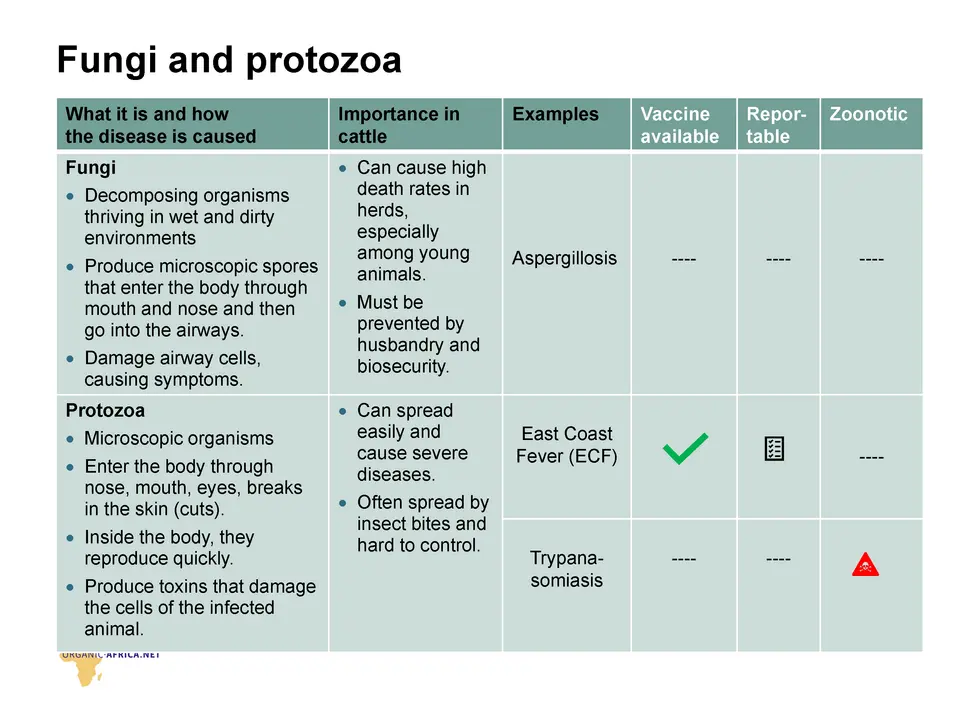

Fungal diseases

Fungi are decomposing organisms that thrive in wet and dirty environments (i. e. like dirty cattle shed). They produce spores, which are microscopic particles that enter the body through the mouth and nose and then travel into the airway. There they damage airway cells, causing signs of disease.

These organisms are important because:

- They can cause high mortality (death) in a herd, especially when young animals are exposed.

- They must be prevented by husbandry and biosecurity, as there is no cure in case of infection.

Treatment: Internal fungal infections cannot be treated, but the load of spores in the air can be reduced by increasing the air flow in the stable and making sure that the environment is dry. Fungi reproduce in wet material, so one should make sure to remove any wet litter and humid fodder residues. A disinfection and husbandry plan can be useful to prevent further fungal disease.

The major fungi in cattle in Africa are:

- Aspergillosis

The fungi or “mold‘ that causes aspergillosis can be present in warm and wet environments, and enters the body when the animal breathes it in. Symptoms can range from mild to severe, with mild cases experiencing coughing and sneezing, and pregnant animals can abort. In severe cases, the lungs are affected and the animal will sneeze, cough, and breathe rapidly before death. Prevention of the disease includes keeping feed areas clean and dry, not feeding moldy feed, and keeping feed safely stored so that it does not develop mold. There are currently no vaccines available for this disease.

Protozoal diseases

Protozoal diseases are diseases caused by microscopic single-celled organisms called protozoa. A common protozoal disease of humans is malaria.

The major protozoal diseases in cattle in Africa are:

Diseases

- East Coast Fever (ECF) (V)

- Trypanasomiasis

East Coast Fever: The protozoan that causes East Coast Fever is transmitted through the bite of a brown ear tick. Severely affected animals will have a fever, discharge from the eyes and nose, bloody diarrhea, and death. Untreated, mortality (death) can be up to 100%. This disease is a major economic and health threat for cattle in Africa. Vaccines are becoming more widely available, and are the best prevention for this disease.

Trypanasomiasis: The protozoan that causes trypanasomiasis is transmitted through biting flies. Symptoms may include weight loss, weakness, swollen lymph nodes, as well as abortions, lower milk yields, lower calving rates and higher rates of calf mortality. The first preventive measure is to reduce the incidence of biting flies by keeping cattle areas clean and free of manure and standing water. Choosing cattle breeds that have some resistance to the parasite is also a good preventive measure – the N’Dama and Boule breeds are the most well known for their tolerance of the parasite. Unfortunately, there is no vaccine available for this disease for either animals or humans, and its development is unlikely given the complex nature of the infection.

Important note: While trypanasomiasis is not contagious from animals to humans, humans can also contract the illness by being bitten by infected flies.

Metabolic diseases

Metabolic disorders occur when there is a problem with the body’s ability to process substances such as proteins, fats, and carbohydrates. In cattle, these diseases can be severe, but are luckily often preventable and/or treatable.

Treatment: Nutrient deficiencies that cause diseases can usually be treated, although some animals may suffer permanent effects. In case of deficiencies, the farmer and the veterinarian can review the feeding protocols to determine what elements might be missing or in excess (for more details, see chapter: Feeding and drinking)

The major metabolic diseases in cattle in Africa are:

- Ketosis

- Milk fever/hypocalcemia

- Grass tetany

- Bloat

Ketosis: Ketosis occurs when cattle cannot consume enough energy to meet the needs of their bodies. This most commonly occurs in female dairy cattle with medium to high milk production levels in the first few weeks of producing milk. Symptoms include unwillingness to eat, weight loss, and weakness. Diagnosis and treatment should be done by a veterinarian, who will have rapid and inexpensive tests to confirm the problem. Treatment involves rapidly returning glucose or glucose precursors (e.g. propylene glycol) to the animal to help regain strength. Prevention involves ensuring proper nutrition prior to and after birth for pregnant and lactating animals.

Milk fever (hypocalcemia): Milk fever occurs when there is not enough calcium present in an animal’s body. This most commonly occurs in female dairy cattle around birth, typically on the first day after birth, because large amounts of calcium are then used for the cow's milk production. This usually only occurs in cows with medium to high milk yields. Symptoms include reduced temperature, the animal will lie down, is unable to stand, with the head turned towards the flank. Without prompt treatment may lose consciousness. Diagnosis and treatment should be done by a veterinarian. Treatment involves intravenous administration (e.g. into the vein) of a solution containing calcium. Prevention involves avoiding foods with a high calcium prior to calving (e.g. legumes such as alfalfa, peanut, clover, and soybean hay)– this stimulates the cow to keep producing her own proper amounts of calcium. Work with a veterinarian to develop a proper feeding protocol for animals near to giving birth.

Grass tetany: Grass tetany occurs when there is a low level of magnesium in the blood. Contributors to low levels of magnesium in forage grasses are high nitrogen and potassium fertilization, rapid growth, poor root penetration depth and acidic or extremely basic soils. Generally, the first sign is “paddling‘ prior to death. Prevention involves making sure animals have constant access to feed containing appropriate levels of magnesium (e.g. by including legumes, which tend to have more magnesium, or by feeding mineral feeds).

Bloat: Bloat in cattle occurs when there is an overproduction of gases in the rumen. This can occur either because an animal is being fed a diet too high in concentrates, particularly those that are too finely ground (e.g. grains, sugars, etc) and not high enough in roughage (e.g. grass, hay, etc), or due to the consumption of certain grasses. Symptoms include gas buildup on the left side of the animal (in the rumen). In the early stages, the animal may kick at the stomach, in later stages it may collapse and will most likely die if not treated. Treatment should be done by a veterinarian and involves passing a stomach tube to release the gases +/- anti-foaming agents depending on the exact cause of the bloat. If a vet is not available, oral anti-foaming agents such as vegetable oil, mineral oil or a quarter cup of mild washing-up liquid dissolved in warm water should be administered. As a last resort, the rumen can be punctured: Find the highest point on the left side of the lumbar region above the udder and insert a large diameter sterile needle connected to a tube attached to a bucket to release trapped air and fluid. Be aware that this will introduce bacteria directly into the bloodstream, which can have serious consequences if you do not act quickly. Adhere strictly to the post-operative care: clean the wound daily, apply topical medication, monitor the healing process and watch out for secondary infections that require drastic countermeasures.

Prevention involves a proper balance of nutrition between concentrates and roughage to encourage rumination and the avoidance of a sudden change of pasture to one containing primarily bloat-causing forage (e.g. wheat, alfalfa, clover, etc.).

Internal and external parasites or “pests”

Parasites can be detected without a microscope, but their eggs are microscopically small. Internal parasites (endoparasites) live inside the body of the animal. The animals take them up as eggs when foraging for food. External parasites (ectoparasites) live in the environment and/or on the animals. They feed on the blood of the animals by biting them (fleas, ticks, horn flies) or on the dead skin and feather cells (lice, mites, grubs). Controlling parasites is of high importance because:

- Internal parasites can cause weight loss, diarrhea, and death.

- External parasites can cause itching, blood loss, and death.

- External parasites, although they usually prefer their cattle hosts, can also affect humans (zoonotic diseases) causing itching, redness, and potentially spreading diseases. Internal parasites of cattle do not affect humans.

Treatment: Parasitic diseases can generally be cured by the administration of the correct anthelmintic drug. As for other medicines, anthelmintics must be applied as prescribed to avoid development of resistance. To prevent external parasites, keep animals groomed and clean, and keep the environment clean as well.

Internal parasites

Controlling internal parasites or ’worms‘ is another important step in herd health.

For organic producers, the first steps in controlling worms is prevention. Producers should take the following steps to avoid worms becoming a problem:

- Establish environments with low parasite pressure. These involve strategies like rotating pastures, with the attention that each area is left without grazing for 4 weeks if possible to allow heat to help with parasite reduction on the pasture.

- Proper animal selection: choosing species and types suitable for local conditions and tolerant to prevailing diseases and parasites.

- Selective breeding: choose animals that are most resistant to diseases and parasites as breeding stock.

- Provide adequate nutrition.

- Keep stress low

Deworming” or “drenching” are the common words for administering a drug or substance to an animal to kill parasites (e.g. ’worms‘ that are living in the digestive tract. These ’internal parasites‘ should be controlled, as when they are too numerous will limit the animal`s growth, productivity, and can even cause death in severe situations.

However, administering these medications can only be done if the preventive measures have failed, and in line with the organic regulations where the farmer is located. Organic regulations explain: 1) which medications can be used 2) and under which circumstances (e.g. age of animal, lactation status, etc.).

It is important to understand and follow these regulations in order to be able to sell animals and products as organic.

In an ideal situation, if worms are suspected, affected animals should be checked for the presence of these internal parasites (e.g. worms) by a veterinarian before treatment. The veterinarian takes a sample of feces (stool), and looks under a microscope for evidence of the worms. In this way, animals that do not need treatment are not treated, the drug chosen targets the correct worms, and money is saved, and avoiding resistance to deworming medications.

However, where this is not practical, animals can be treated based on general local conditions and symptoms.

Different medications are available that target different groups of these ’worms‘, and these should be discussed with a veterinarian or extension agent.

External parasites

Preventing and controlling external parasites or ’pests‘ is also an important step in a healthy and productive herd. ’Pests‘ include ticks, lice, fleas, mites, flies, and other biting and sucking pests.

Like internal parasites, these pests also affect the health, wellbeing, and productivity of a herd, and can even cause death in severe cases. Some, like ticks, can also spread contagious and deadly diseases, and should be prevented if possible.

Prevention is again the first step in controlling these pests, and the preventive measures depend on the pest in question. In general, well-fed and healthy animals are less likely to get attacked by pests. Some pests are very difficult to prevent, and therefore must be controlled to avoid production losses.

Common prevention measures include keeping areas clean and dry, avoiding overcrowding of animals, and in some cases using multi-species grazing to help control parasites (e.g. grazing chickens with cattle). Especially areas where calves are grazing are less likely to be contaminated with parasites.

Ticks: Ticks are bloodsucking pests that also transmit a variety of harmful diseases. As ticks are omnipresent in the natural environment, particularly for grazing animals, prevention is difficult. The best strategy is control with available local resources. Commonly available controls include chemical sprays or dips that are administered on a regular basis by the government or extension agents. Less commonly available but also effective are vaccines and injectable treatments. As with other chemical methods, care must be taken when using them to adhere to organic standards.

Lice: Lice are also bloodsucking pests that cause skin irritation and loss of productivity. Preventive measures include examining new animals for lice, and treating before they enter the herd. Some animals have consistently high loads of lice and ’carry‘ them to the rest of the herd. These animals should potentially be removed from the herd. Avoiding overcrowding and providing good nutrition also reduce the likelihood of a lice problem. Control measures include chemical sprays.

Mites: Mites are biting pests that generally live in the environment (e.g. dirty bedding in a stable, etc). They can cause skin irritation and loss of productivity. Preventive measures include keeping animals outside as much as possible, avoiding overcrowding in indoor housing, and providing proper nutrition. Control measures generally include chemical sprays.

Flies: Flies are biting pests that can also spread disease. They can also cause irritation and loss of productivity. Preventive measures involve keeping indoor areas clean and dry, and avoiding overcrowding. Control measures involve the application of an insecticide as a dust, spray, or treated ear tag.

Horn flies: Horn flies are bloodsucking pests that can cause severe skin irritation and loss of productivity. Unlike regular flies, horn flies stay on the animal day and night. Large numbers can cause a loss of condition and lower milk production. Control measures that have been found to be particularly effective include passage beneath a bag with an insecticide “dust bag” that animals must pass underneath on the way to food or water that releases small amounts of the insecticide “dust” when touched by the animals.

Grubs: Grubs begin their life as eggs laid on the back of cattle by the heel fly. Once the larvae hatch, they burrow or bite their way through the skin. As they grow and mature, they migrate underneath the skin, causing damage to the muscles, connective tissue, and skin as they move and eat. Once they are in their preferred location, they cut breathing holes in the skin of the cow. Infestation with these parasites causes severe skin irritation and loss of productivity. Control measures include the use of insecticides.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.