Animal Management

The aim of good animal and herd management is to keep the animals healthy and productive in the long term and to farm cost-effectively. The management of the animals is tailored to their age, breed and production method and includes daily care and feeding. The following chapter deals with specific care measures for cows giving birth, calves, heifers, lactating cows, dry cows, fattening animals and, draught animals. The topic of feeding is dealt with in greater depth in the "Feeding" chapter.

Overview of the phases of life of a (dairy) cow

| Phase | Age or duration | Important aspects (summary of following chapters) |

|---|---|---|

| Birth | 0 |

|

First hours after birth | 1 – 10 h, most important in the first 2 hours |

|

Calf rearing | 0 – 1 year |

|

| Heifer | 1 – 2 years |

|

| Calving | Around 2 – 3 years old |

|

Lactation: Start phase | Lactation day 1 – 100 |

|

| Lactation: Production phase | Lactation day 101 - 300 (or longer) |

|

| Dry phase | 40 – 80 days |

|

| Calving | Lactation day 0 | |

| … several Lactation cycles … | ||

| Slaughtering |

Cows - Pre-calving and birth

Separation of cows in last stage of pregnancy

Depending on the breed, the farming system, and the husbandry system, heavily pregnant cows may be separated from the herd for closer observation or may be left to calve naturally. Herds where animals are able to calve on a safe, quiet and clean pasture and who generally have easy births may do best if left with the herd. However, if these conditions do not apply or if cattle are kept in sheds, animals may do better if separated from the herd and given a small, safe, clean space to calve either in the shed or close to the homestead. It is important to observe calving and change calving conditions if difficulties appear regularly.

Advantages to separating an animal include the ability to monitor the animal regularly before birth, a safe, clean place for the calf to be born, and an easy location to help with the birth if necessary. Disadvantages can include stress for the mother cow if the calving pen is not adjacent to the herd. If the separation is too stressful, this must be weighed against the advantages.

Calving

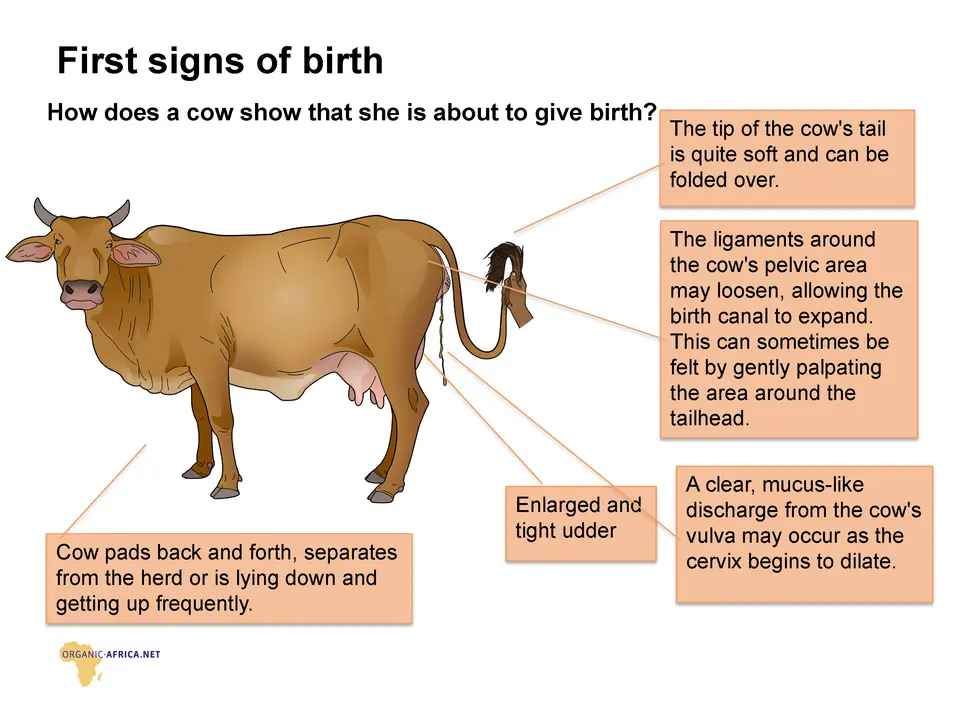

The gestation period varies in different breeds, but usually lasts around 280 days. About two to three weeks before the due date, the udder starts to enlarge and a thick line of mucus comes out of the vulva. In some cows, this process starts later, up to only 24 hours before birth. These are the first signs that a birth of a calf is approaching and the cow should be separated if this is part of the management plan.

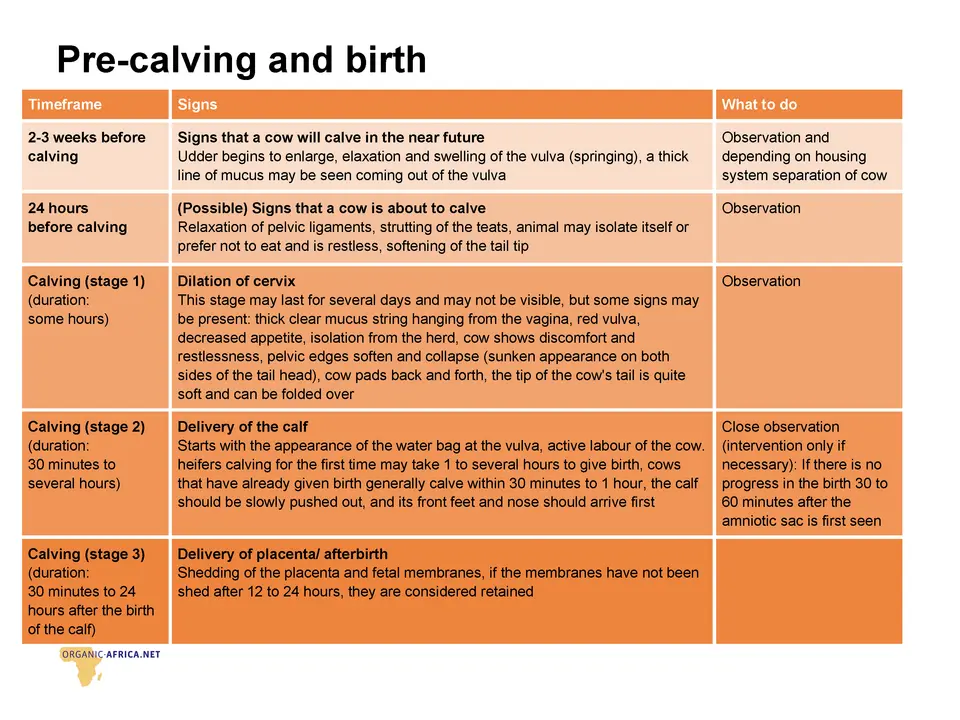

See in the following table the normal progression of pre-calving and birth:

Birth assistance

Calving (stage 1) - The first signs of birth itself are as follows:

- Pelvic edges soften and collapse

- Lactation starts

- Cow pads back and forth

- The tip of the cow's tail is quite soft and can be folded over

- Cervix dilates and the amniotic sac can be seen - it must not be broken at this stage!

When to intervene? (during stage 1)

As long as no problems appear, the cow should be left alone during birth. If problems appear, calm support may be necessary.

Calving (stage 2) - As soon as the water has broken, the next phase of birth occurs, which can last 30 minutes to 6 hours:

- Contractions begin (muscle contractions in the uterus)

- Abdominal squeezing begins (muscle contractions in the abdomen)

- The calf is pushed out with the front legs and then with the head in thrusts.

When to intervene? (during stage 2)

- If birth takes a noticeably long time, a cleaned and sanitised hand and arm can be inserted into the vagina to feel if the calf is in the correct position. Knowledgeable persons may be able to correct the misplacement of a calf.

- In case of intervention, the highest hygiene rules must be followed. One should only reach into the cow with well-washed hands and arms and use enough lubricant!

- If there are problems that cannot be safely managed by those present, the veterinarian should be called. Depending on the situation, the cow can be helped in this phase by pulling on the calf. But this should be done with care. Pulling too early or too hard can cause damage to the calf and the cow. One should only pull when the cow is pressing.

Calving (stage 3) - After the complete calf has been born, the last phase follows:

- The afterbirth (placenta) is expelled from the cow with contractions

When to intervene? (during stage 3)

The afterbirth should come out after 12-24 hours at the latest. If this doesn’t happen, medication (plant medicine or pills) can be administered. If a farmer is not sure what to do, a veterinarian should be called. Delayed expulsion of the afterbirth (placenta) may lead to problems such as uterine atony, infection or other health issues.

Calves

The care of the newborn calf includes:

- Checking the breathing: if the calf is not breathing normally, remove the mucus from the mouth and move the front legs in circles (massage the lungs and heart), rub/massage the calf with straw, hold the calf up by the hind legs and carefully swing it, empty cold water over the head.

- The calf is rubbed dry and given to the mother to lick (if the cow is used to humans).

- If the calf is breathing normally, the cow and the calf can be left alone with monitoring from a distance.

- The calf stands up and drinks the colostrum (next section).

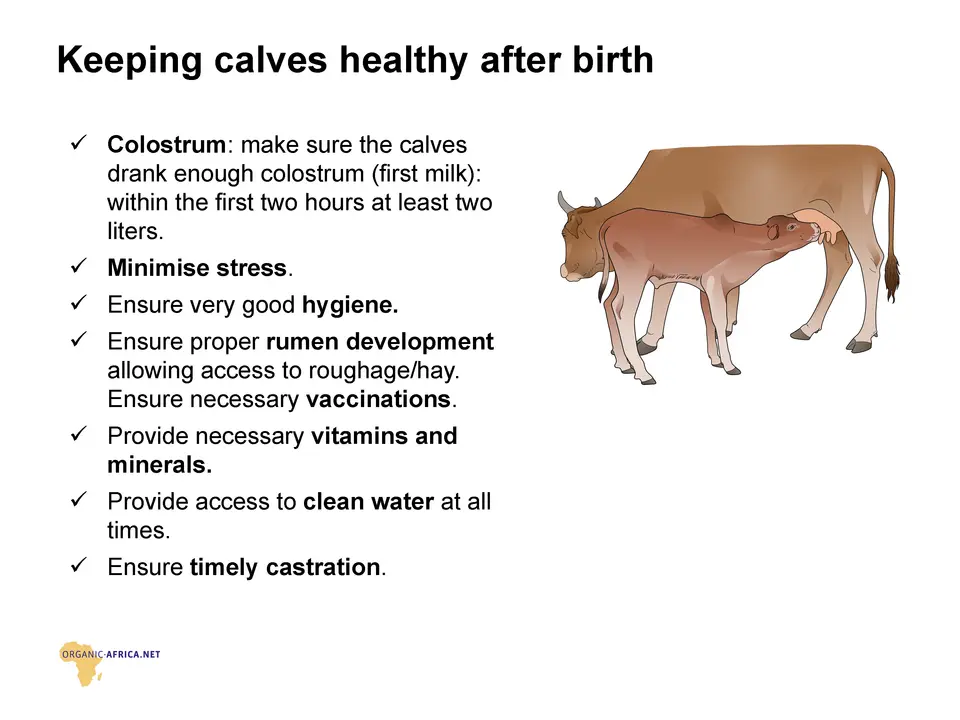

Colostrum

The first milk that the calf drinks after birth has a different composition than the milk that the cow normally gives. The first milk is called "colostrum" and contains antibodies against diseases, which the calf needs to build up an immune system. It is, therefore, imperative that this is received by the calf after birth, preferably in the first three hours. This should be well observed and if it does not drink, or it only drinks too little, the calf must be helped. Drinking from the mother cow directly is preferred but it is also possible to milk out the colostrum and give it to the calf with a teat bottle.

Separation of calves

Regarding the separation of calves there are several options about how this can be done or not:

| Practice | Implementation | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| No separation (mother cow system in beef cattle) | Calves are left with the mother cow until weaning. Usually applied in beef cattle systems. | Best animal welfare Increased weight gain of the calf during suckling compared to conventional rearing Calves show better social behaviour than in conventional rearing | Risk of diarrhoea because of calves drink too much milk |

Separation on the first day (conventional rearing) | The calf is separated from the mother cow and grows up in a group of calves, fed with milk and roughage. The cow is milked by humans. | More milk for human consumption | Low animal welfare Separation stress for mother cow and calf |

Nurse cow | The calf is either directly after birth or later separated from the mother and brought to a nurse cow. The nurse cow is usually the mother of a calf and also fosters other calves from other cows. Calves can have permanent or short-term contact (2x a day the calf can suckle, usually before or after milking) | Good animal welfare Stress at feeding time (if short-term contact) Increased weight gain of the calf during suckling compared to conventional rearing Calves show better social behaviour than in conventional rearing | Risk of diarrhoea because calves drink too much milk |

| Cow-reared calves in dairy systems | The calf has either permanent or short-term contact to the mother cow for suckling. The mother cow is also milked. | Good animal welfare Stress at feeding time (if short-term contact) Increased weight gain of the calf during suckling compared to conventional rearing Calves show better social behaviour than in conventional rearing | Risk of diarrhoea because of calves drink too much milk |

Find more information on cow- and nurse-reared calf husbandry in this guide.

Keeping calves healthy

As the calf does not have a fully developed immune system in the first weeks of life, it is particularly susceptible to diseases. The following measures can be taken to prevent diseases in calves:

- Reduction of stress: no overcrowded calf hutches, if calves are separated from the herd, plenty of fresh air, protection from cold, heat and strong winds, no transport before 4 weeks of age.

- Clean environment: possibility to lie on a well-littered, clean and dry area.

- Rumen development: From one week of age, the calf should have access to roughage, for example, hay. This is important to allow the rumen to develop slowly.

- Slow feed change: To allow the calf's digestive system to adapt, the change in feeding should be spread over several days.

- Vaccination: Calves can be vaccinated against some diseases, which helps them withstand an attack by this disease. Which vaccinations are useful varies from country to country and depends on the farm itself and on the availability and cost of vaccines. Ask your local veterinarian what is appropriate for your farm. For more information on vaccinations go to the Health chapter .

- Supply of vitamins and minerals: A sufficient supply of all vitamins and minerals is important for the calf to grow well and stay healthy later on. Milk has many good ingredients, but not all the necessary ones for the calf. For example, a calf that is fed only milk and has no access to pasture or soil will be iron deficient. The natural source of iron for calves is soil and roughage. Milk alone has too little iron for the calf, therefore calves should always have access to roughage.

- Calves outdoors: Giving calves access to an outdoor area is generally favourable for their healthy development. The "calf pastures" should be moved regularly and grazed alternately by adult animals and then calves again. This is because certain parasites are particularly dangerous for calves. The parasite pressure in the soil increases the longer the calves are on the same field. In humid areas, care must also be taken to fence out standing water, as parasites can also be found there.

- Water: Calves start drinking water shortly after birth. They should have continuous access to clean water in a bucket or trough (not from a teat bottle) from the beginning.

- Calf-Human Relationship: Calves that are regularly touched and stroked from the second day after birth become more trusting, even towards unknown people who approach them in the pasture or in the barn later on. Early habituation to positive contact with people can reduce stress-indicating reactions in the cattle. This effect can last for several months at least.

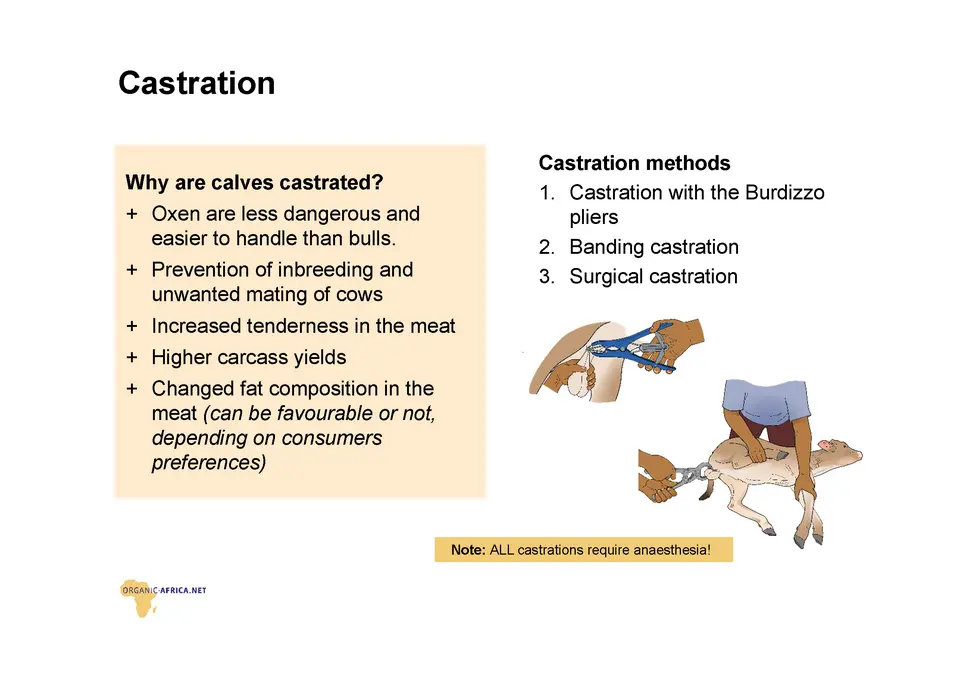

Castration

Advantages of castration

Castration provides several benefits for both the farmer and the cattle. Firstly, castration reduces aggression and unwanted sexual behavior in male cattle, which can be dangerous and disruptive in herds and during draught animal work. Castrated cattle are easier to handle, and they pose less of a risk to the farmer and other animals.

Secondly, castration reduces the risk of breeding-related problems, such as unplanned pregnancies, inbreeding, and genetic defects. It also ensures that only the best and healthiest animals are used for breeding, thereby improving the overall quality of the herd.

Thirdly, castration can modify carcass characteristics and, depending on local consumer preferences, lead to increased meat quality, including tenderness and marbling. Castrated animals have a higher meat-to-bone ratio, which increases the amount of saleable meat.

Disadvantages of castration

Castration causes pain and stress in the calf and can lead to infections. Castration also leads to a reduction of growth rates compared to bulls and may take longer to reach market weight. It may also be against ethical principles to castrate an animal.

Castration methods

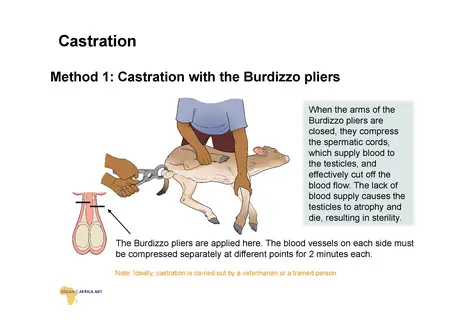

There are several methods of castration used in Africa, including surgical, chemical, Burdizzo tongs and banding. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages, and it is essential to select the most appropriate method based on the age and size of the animal, as well as the farmer's experience and available equipment. Every farmer who wants to castrate its bulls should learn it from a veterinarian. It is important, that the method is applied correctly to prevent infections and pain and to achieve a complete castration.

- Burdizzo: The burdizzo is an instrument that has two arms with curved ends. When the arms are closed, they compress the spermatic cords, which supply blood to the testicles, and effectively cut off the blood flow. The lack of blood supply causes the testicles to atrophy and die, resulting in sterility. To perform the burdizzo method, the animal is restrained or held down to prevent it from moving. The scrotum is then shaved and cleaned to prevent infection. The farmer then takes the burdizzo and applies it to the base of the scrotum, above the testicles. The arms of the burdizzo are closed firmly to crush the spermatic cords and blood vessels. The burdizzo is held in place for 60 seconds to ensure that the cords are crushed completely. This procedure must be performed twice on both testicular strands to perform a complete castration. The second squeeze always occurs below the first. Then the bruised area is disinfected. After the procedure, the animal should be monitored for any signs of infection or discomfort. After about 4 to 6 weeks, it should be checked whether the testicles have shrunk. The Burdizzo method can be used to achieve complete castration in calves older than 2 months.

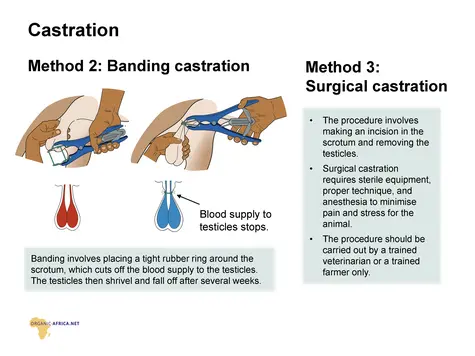

- Rubber ring/band: Banding involves placing a tight rubber ring around the scrotum, which cuts off the blood supply to the testicles. The testicles then shrivel and fall off after several weeks. This method is cheap and easy to use and it is usually less painful for the calf than the burdizzo tongs. Banding is only suited for young animals (less than two weeks), and it is important to monitor the animal for signs of discomfort, infection, or self-mutilation.

- Surgical castration: The procedure involves making an incision in the scrotum and removing the testicles. Surgical castration requires sterile equipment, proper technique, and anesthesia to minimise pain and stress for the animal. The procedure should be carried out by a trained veterinarian or a trained farmer only.

Pain elimination

Animals, like humans, also feel pain. Any form of castration is very painful and unpleasant for the animal. Using local anaesthesia (i.e. making a certain part of the body insensitive) and/or pain medication can reduce the pain. Local anaesthesia must be used for any form of castration. Sedation alone is not enough; it sedates the animal but does not suppress the pain it experiences during the procedure. The exact handling of anaesthesia is regulated in many countries by animal protection laws and in the organic standards.

Dehorning

Cattle are dehorned to ensure safer and easier handling of the animals. Furthermore, stress and injuries can occur when horned animals play or fight in an unsuitable environment. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that organic animal husbandry should always correspond as far as possible to the natural conditions of the animals, which in principle also includes having horns. It should therefore always be tried to adapt the environment and the husbandry to the animals before animals are dehorned.

If animals are to be dehorned anyway, the following must be observed:

- Choose the right age: Dehorning is generally performed between 2 to 8-week-old calves.

- Dehorn animals in a season which is not a fly season.

- Dehorning is carried out by a trained person or a veterinarian.

- Choose the right method by an expert:

- Hot iron: An iron is heated and held firmly to the horn bud for about 20 seconds, destroying the horn and preventing further growth. It is very painful for the animal.

- Dehorning paste: In young calves (before 4 weeks), a corrosive paste is applied to the growing horn base to prevent growth. This is problematic regarding animal welfare as it cannot be ruled out that the paste will also get onto other parts of the body or other animals or be licked off by the other animals.

- Sedation and/or restraining is recommended.

- Administer local anesthesia before dehorning. This must be done by a veterinarian or a trained person. Depending on the local animal protection law and organic standards it may be required.

- Administration of pain medications during and after dehorning.

- Choose a dehorning method: Hot iron dehorning is the least painful dehorning method and is recommended. The heat destroys the horn-producing skin and the base of the horn. The size of the dehorning iron must be chosen according to the size of the calf`s horn.

Heifers

What is a heifer?

A heifer is a young female cow that has not yet given birth to a calf. Typically, heifers are between the ages of one and two years old and are still growing and developing before they reach maturity. Heifers are important in cattle production as they are the future milking cows and beef producers in the herd. Proper management of heifers is critical for their long-term health and productivity, as well as for the overall success of a cattle production enterprise.

Feeding of heifers

Heifers should receive a balanced diet that meets their nutritional requirements for optimal growth and development. The diet should consist of roughage, such as grass, hay, or silage, as well as protein and possibly mineral supplements. Adequate amounts of clean water should be available at all times. 1 to 2 weeks before giving birth for the first time the feeding ration of heifers should slowly be changed to the ration that will be fed as soon as the cow gives milk. It is important that the cow eats enough after birth and should, therefore, already be used to the lactation ration as soon as she gives her first milk.

It is essential to monitor heifers' weight gain (see Body Condition Score) regularly, as underfeeding or overfeeding can have negative consequences. Underfeeding can lead to stunted growth, delayed oestrus cycle and poor reproductive performance while overfeeding can result in obesity and metabolic disorders.

Cows - During lactation

Good management of lactating cows includes

- Good feeding: appropriate to milk production and ruminants.

- Good health: good feeding, good hygiene, appropriate housing system, appropriate treatment of sick animals, good claw care

- Animal-friendly housing: able to show natural behaviour, no permanent tethering or isolation

- Good reproduction management: normal reproduction cycle, good heat detection, planned reproduction

- Good human-animal relationship: low-stress animal and herd handling

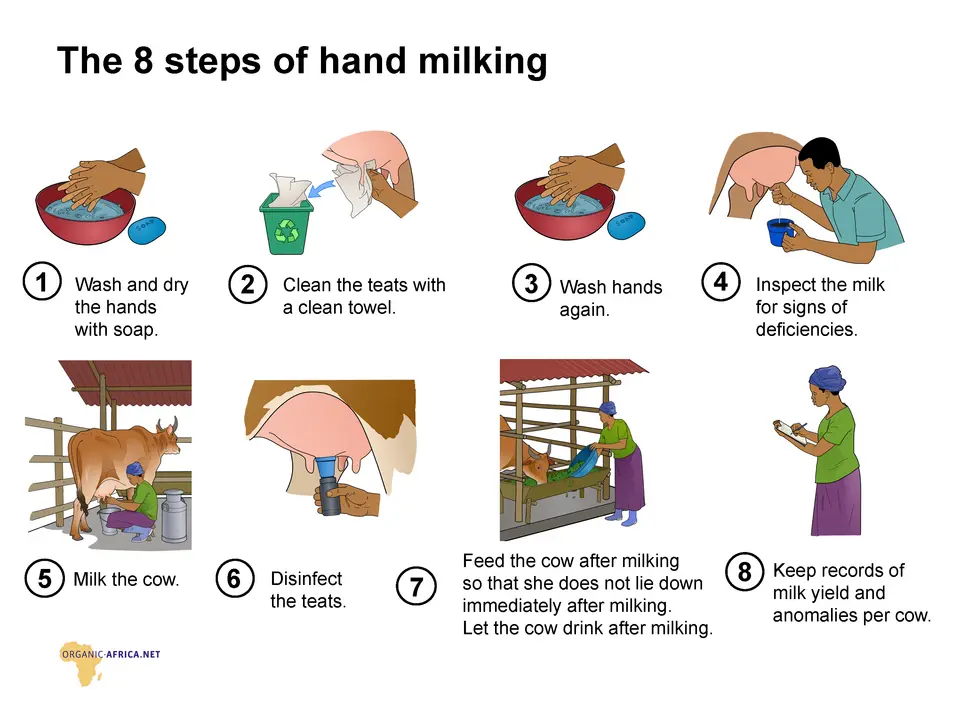

Hand milking in 7 steps

A correct milking procedure is enormously important to ensure good milk hygiene and not to endanger the cow's udder health. In order for the milk to be safe for consumption and easy to process, it must be hygienically impeccable. Next to milk storage, milking is the main risk for contamination. The correct procedure for hand milking is described in the following illustration:

Practice | Risk Factors |

|---|---|

1. Milkers wash their hands before milking with water and soap. Important to dry the hands with a clean towel. | Pathogens are everywhere, on the floor, on an animal, in the air. Hands must be clean so that pathogens do not get on the teat and thus into the milk or udder. |

2. The udder and all teats are cleaned with a clean towel. Use a different towel for each cow. | Pathogens can be transferred from one cow to another by using the same towel. |

3. Clean the hands again. | |

4. Massage the teats and start milking. Visual inspection of the first jets of milk on flakes: Do you see any changes in homogeneity? For this, a strip cup is a suitable tool. | If flakes are visible, this is a sign of a possible Mastitis infection in the cow. |

5. Make rhythmic and even movements with the fingers. Use both hands for milking and milk alternately. | Milking should be done quickly and it should be comfortable for the cow, otherwise she will become restless, withhold milk or show defensive behaviour during milking. |

6. Right after milking dip every teat in a special teat dip for udder disinfection. | The milk flows through the teat duct, the opening at the bottom of the teat. This channel remains open for a while after milking. Pathogens can get into the udder. Therefore, disinfection is important to prevent udder infections. |

7. Make sure the cow does not lie down directly after milking. Let her stand for at least one hour. To ensure this, feed has to be provided. | Many pathogens are found on the floor. When the cow lies down, the udder touches the ground and pathogens can easily enter the udder through the teat duct. (Always clean the bedding before milking the cows.) |

8. Record the amount of milk and any anomalies observed in the milk of each cow every time. | Milk yield provides valuable information about feeding and the cow's state of health. |

Dry cows

Milk yield decreases with time over the lactation phase. When a dairy cow is producing less value than she is consuming, milk production is not profitable anymore. The cow is then “dried up”, meaning milking is stopped. The dry period is a period of rest for dairy cows where they are not milked and allowed to recover before calving and starting a new lactation cycle. It typically lasts for about 60 days, but can range from 40 to 80 days depending on the cow's condition and other factors.

The dry period is essential for the overall health and productivity of dairy cows for the following reasons:

- Mammary gland regeneration: During the dry period, the mammary gland undergoes a process of regeneration, where the secretory tissue is replaced with new tissue. This regeneration is necessary for maintaining milk production in subsequent lactations.

- Metabolic recovery: The dry period provides an opportunity for cows to recover metabolically, allowing them to replenish body reserves that were depleted during the previous lactation.

- Improved immune function: The dry period is also essential for improving the cow's immune function, allowing them to better resist infections and diseases in the next lactation.

- It also helps synchronise the cow's reproductive cycle, making it easier to manage breeding and calving.

Overall, the dry period is crucial for maintaining the long-term health and productivity of dairy cows. It allows them to recover, regenerate, and prepare for the next lactation cycle, ensuring a consistent and sustainable supply of milk for dairy production.

When keeping dry cows, special attention should be paid to clean and dry lying areas and adapted feeding. Even if the cow is not milked, many udder infections originate at this stage. On the one hand, the time is important for the recovery of the udder, on the other hand, bacteria can easily penetrate the udder and multiply if the teat is not completely closed. This can be caused, for example, by incorrect drying off (too early, not abrupt enough, incorrect feeding) and can show as an udder that is still dripping.

How to dry off a cow?

Cows should only be dried out when the milk yield has decreased significantly. Lactation can be terminated by a change in feed, omission of milking or omission of suckling by the calf. This usually happens after about one year. However, the cow can also continue to be milked and only be inseminated again when she hardly gives any more milk. This depends on the strategy, breeds and feed availability of the farm. As a rule of thumb, a cow should not be dried out above the daily milk yield of 15 kg milk (this applies for high-grade milk breeds). Small-scale farmers usually dry off cows around 3-4 kg milk. Drying is best done abruptly, i.e. no more milking from one day to the next. It is important that the cow is fed only low-energy and low-protein feed, which automatically leads to a decrease in milk quantity. The abrupt cessation of milking increases the internal pressure in the udder, which interrupts milk production and promotes the regression of the udder cells. A substance then forms in the teat canal which closes the teat and protects it from invading bacteria. During the dry phase, the cow should continue to be fed low-energy and low-protein feed. She should not lose too much weight, as she needs additional energy for the growth of the calf, but also not become too fat, as this would be unfavourable for the birth and the start of the next lactation. About 1-2 weeks before the calf is born, the ration should be changed to the lactation ration. This will help to ensure that the cow eats sufficiently immediately after birth.

Fattening animals / Beef cattle

Cattle intended primarily for the production of meat are fattened. Cattle breeds in organic farming have several purposes and can be suitable for milk production and meat production. Either the animals are fattened on the farm or sold to a beef cattle farm. Beef cattle that are reared for meat production usually reach mature weight at a younger age (2 - 4 years) than dairy cattle. The feeding and husbandry of these animals may differ from animals that are primarily intended to give milk (see chapter feeding).

Draught animals

In many areas, cattle may be used for draught animal work. Both male and female cattle can be used, although male cattle are used more commonly because of their larger size. Animals of any breed can be used, and once trained and of mature age are commonly then called oxen. Draught animals are generally used and trained as pairs, and a well-trained team can be used in the fields for many years. However, for very small farms, a single animal/ox can also be very useful for relatively light work. For those new to using draught animals, finding an experienced neighbour or mentor is critical to gaining the skills necessary to properly use and care for draught animals.

Choosing animals

When choosing two animals for a team, look for animals that are well built (e.g. strong straight legs, a strong well-muscled neck, etc.), have a similar size to each other, and perhaps most importantly a gentle and willing temperament.

Training animals

Cattle are intelligent animals and are relatively easily trained. The easiest time to train an animal is when it is young, and simple training can begin as early as one month of age. Short training sessions of 15 minutes per day will yield a very well-trained animal, by the time it reaches its full size and strength. Although there is some variation with breed, oxen are generally considered mature and ready to perform full work at around four years of age.

Feeding and water

Animals used as oxen should be given special feeding consideration to ensure that they are able to do the work expected of them during the growing season. Ideally, they should be well-fed before the start of the growing season to allow for optimal performance. It can be relevant to store feed for draught oxen after the rainy season to feed to them before the next growing season to increase their body condition. When performing hard work for many hours a day doing work such as ploughing, oxen should ideally receive additional feed, and should be offered water at frequent intervals during work. For more information, see the feeding section.

Working

Oxen are sensitive to heat, strenuous activities such as ploughing should be planned in the early morning or in the evening, and not in the heat of the middle of the day. If the oxen are breathing hard and appear tired, it is a good idea to take a short break in the shade. In case of moderate heat, bring some water and pour it over their backs to help cool them down. Equipment should be chosen to match the strength of the draught team, and consideration must be taken of the depth that the equipment will go, the hardness of the soil, and other factors that will affect the load that the animals must pull. If the load is too great, the animals may be unable or refuse to pull it, or will tire quickly and the work will not be finished. Working with an extension agent trained in draught animal operations can be very helpful in choosing proper equipment that suits the farm and the draught animal power available.

Equipment

It is important to have properly adjusted and well-fitting equipment to maximise the comfort and performance of an ox team. Yokes should be wide and carefully smoothed and rounded where they touch the neck to avoid injury and discomfort to the animals. After working, it is good to check the neck and body of the oxen to ensure that there was no rubbing of the equipment, and to make adjustments if necessary.

Find more information on the topic of draught animals here:

Ox Power Handbook (1986, revised 2019): https://iscowp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/OX-POWER-HANDBOOK-1.pdf

Training in the ring: https://iscowp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ox-training.pdf

Working Steer Manual: https://extension.unh.edu/sites/default/files/migrated_unmanaged_files/Resource002680_Rep3965.pdf

Claw care

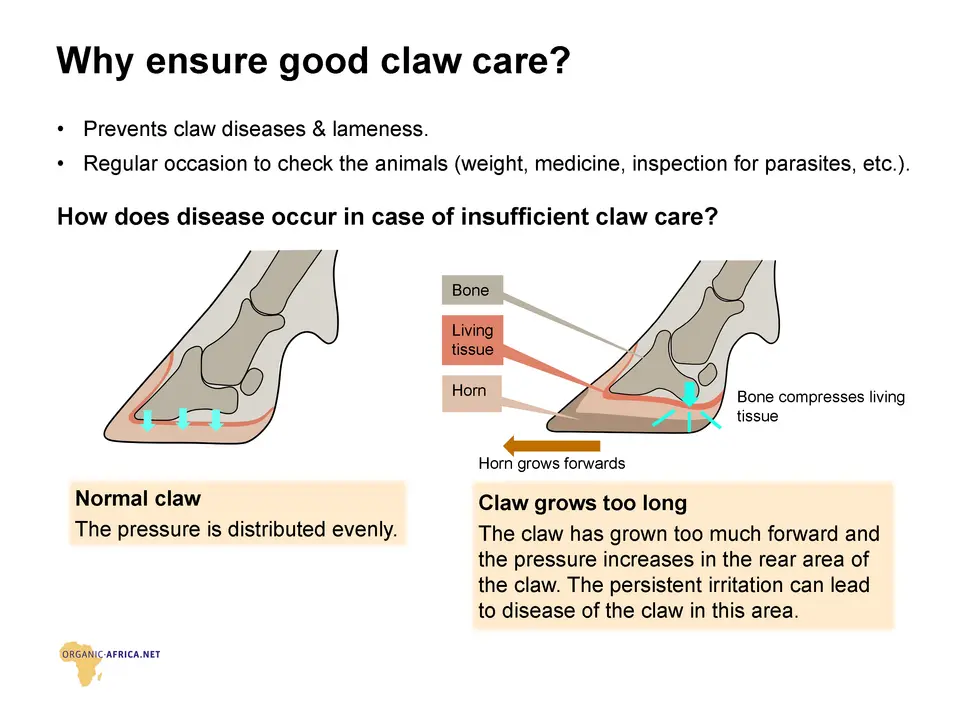

The claws of cattle are naturally rubbed off and shortened by walking on rough ground. In agro-pastoral systems where cattle are moved and grazed outside, this is usually the case and the claws don’t need to be trimmed regularly. When cattle are kept confined or the soil is very sandy without any stones, in most cases, this is done insufficiently or irregularly. As a consequence claws get too long, which can provoke faulty weight bearing on the claws and thus diseases (see illustration). This in turn can lead to the loss of the animal, to high veterinary costs or to reduced performance (milk yield or weight gain). A cow that is lame and in pain does not eat normally, shows less clear oestrus/heat symptoms, possibly gives less milk and has lower gains. A good cow stands on healthy hooves! Regular care and inspection of the claws are therefore extremely important in order to have long-living, healthy animals.

Insufficient claw care - how does disease occur?

The horn of the claw surrounds the bones, and in between, there is sensitive tissue that is very well supplied with blood. If the claw grows too much, it grows forward. This causes the whole claw to tilt slightly backward. The bone thus tilts backwards with it and the weight is no longer evenly distributed. The rear part of the bone now presses on the sensitive tissue and disturbances occur. This is how ulcers and diseases can develop, causing severe pain in the cow.

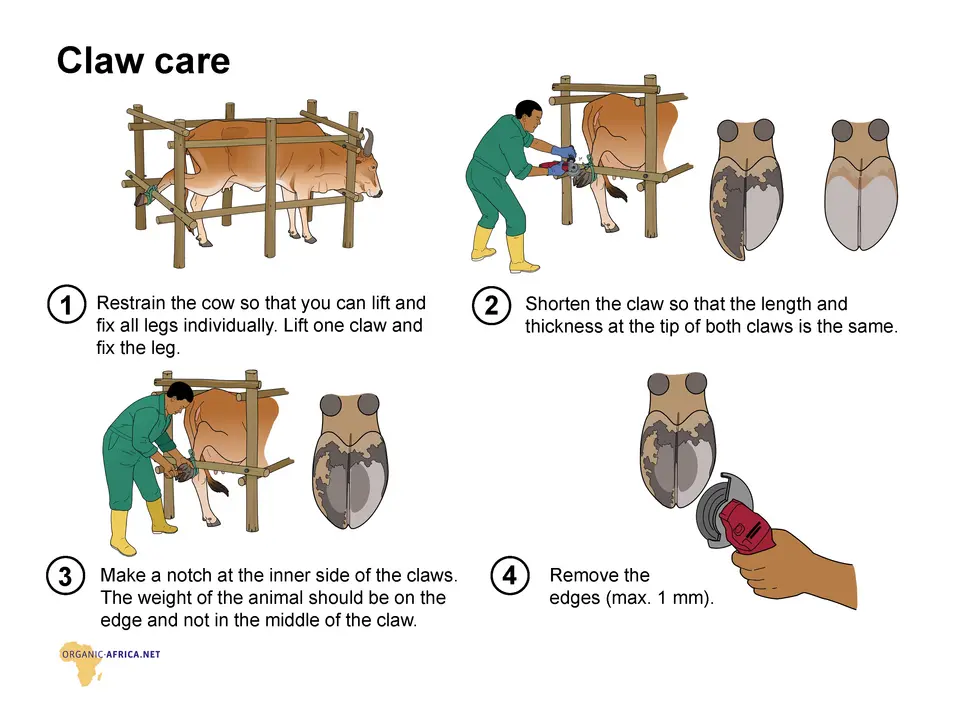

Claw care - how do I trim claws correctly?

Claw care is basically about ensuring that the cow's weight is equally distributed on all 8 claws (the cow has two claws per leg, one inside and one outside). For this to be the case, all claws should be as equal in length as possible. During claw care, claws that are too long are shortened. The farmer should do this 1-2 times a year. It is best to have someone experienced to teach you the following steps:

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.