Introduction

In Cameroon and many other countries in Africa, potatoes have become very popular in the last decades because of their versatility and suitability for direct marketing. However, for commercial potato production good yields are necessary to cover the costs for quality planting material, fertilizers, pesticides, labour and mechanisation, if available. For the production of quality tubers and for minimizing losses, key requirements of the crop must be considered at different stages of production ranging from seed preparation through nutrient and water supply, plant protection and harvest to storage and transport.

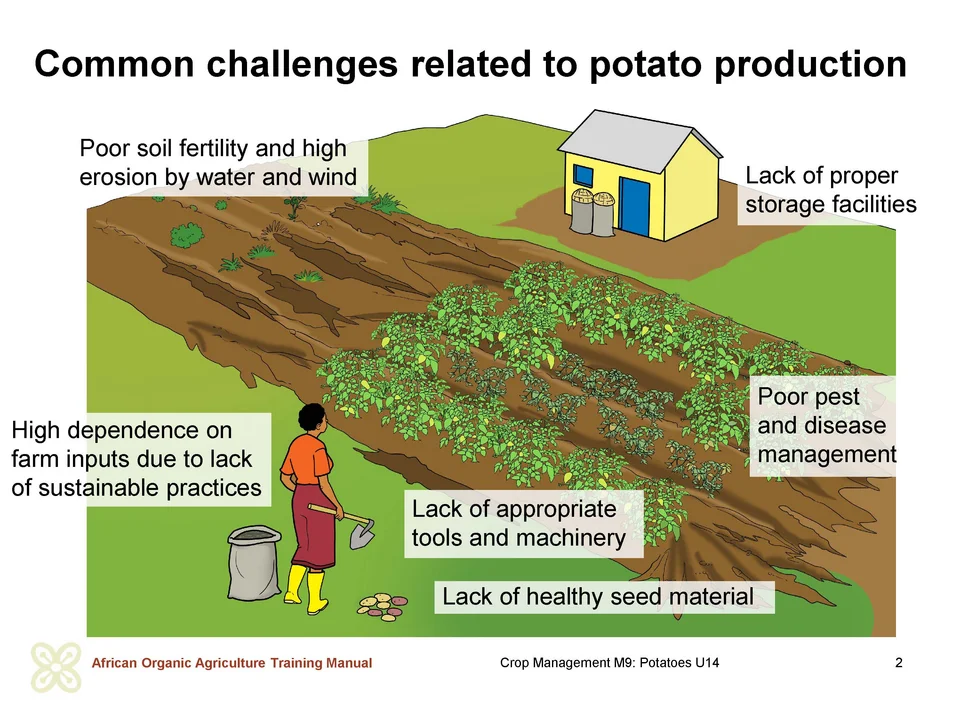

A GIZ project identified the following challenges as key limitations to the attainment of potentially high yields by smallholder farmers:

- Limited access to quality seed potatoes due to local unavailability

- Long distances to distributors of seed potatoes and high price of the seed

- Low levels of production input use (especially fertilisers and pesticides) due to limited access (physical and economic) to quality inputs

- Limited access to information on good agricultural practices (GAPs), which contributes to inadequate management of pests and diseases.

General situation regarding potato production in Cameroon

Climate

Due to the crop’s moderate temperature requirements, potatoes are cultivated mainly in altitudes between 1,000 to 3,000 meters above sea level in the West and Northwest regions of Cameroon. Most farmers cultivate the crop during the rainy season, which begins in March/April and lasts until November. Rainfalls increase until August/September and decrease towards November. The main potato production period in Cameroon is between March and mid-July. The period between November and March is the dry season with little agricultural activity. However, farmers with access to irrigation water cultivate their land in the dry season, too. With adequate irrigation potato production is possible all year round.

Soils

Most soils in the potato production regions in Cameroon are highly eroded laterites (loams) that developed under intensive and long-lasting weathering. Such soils are commonly found in the humid tropics in Africa.

Because of intensive depletion and use of acidic chemical fertilizers, the soils have a low pH ranging from 4.4 to 5.5 (whereas the optimal range for potato is at pH 5.5 to 7), a low organic matter content and, as a result, also a low water-retention capacity and low nutrient contents including nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium and magnesia from the mineral fraction. Poor soil structure due to low organic matter content encourages widespread erosion and silting of the soil surface. In contrast to the soils situated in lower production areas, the soils of higher areas are sandier with a higher organic matter content.

Land preparation and mechanization

The mechanization level is generally low. Most farmers rely on hand hoes for land preparation, weeding and harvesting. The use of modern and efficient hand-tools is not widespread.

Varieties and availability of good quality potato seed

The availability of quality potato seed is low and access is difficult for most farmers. Certified organic potato seed is not available so far. In the past, potato seed was imported from Europe and Kenya. However, due to inappropriate transport and storage, and inefficient distribution to farmers a significant proportion of the seed tubers was lost before reaching the farmers.

In the 1990s improved varieties such as Cipira and Tubira, which were developed by IRAD and CIP for Cameroon, were introduced in practice. Both varieties were widely adopted because of their high production potential and tolerance to the devastating disease, late blight. The two are still the most common varieties in Cameroon. In the last decades, other varieties have been evaluated over a wide range of ecologies, with different results. “Local” varieties and so-called “European” varieties such as Cardinal, Desirée, Diamant, Hydra, Kondor, Roman, and Spunta are cultivated as well. Newer varieties to Cameroon are Dosa, Panamera, Jacob, Pamina, Joelle, Jelly, Bavapom, Sevim and Krone.

Since the introduction of new varieties, only a very limited amount of healthy potato seed from the national research sector was provided. In addition, many smallholder farmers cannot afford certified quality planting material, as it is too expensive. As a result, farmers have multiplied tubers of long-established varieties on their farms over decades. Due to continuous re-use of own plant material and unsuitable propagation practices the cultivated varieties have degenerated from viral infection or have become susceptible to late blight. A few seed suppliers exist in Cameroon and provide organically grown vegetable seeds and potato seed tubers. But the seeds are not certified organic nor guaranteed healthy.

Farm types and soil fertility management practices

The smallholder farm sizes in Cameroon range from 1 to 5 hectares, but most potato farmers own less than 2 hectares of agricultural land. Crop producing farmers traditionally do not keep farm animals apart from some free-range chickens and a few pigs. The small amounts of farm manure are mostly not used for fertilization of the crops. The culturally conditioned separation of stock and crop farmers restricts the use of animal manure in crop production. Traditionally, fertilisation of crop farmers relies on a two year green fallow based on volunteer plants on half of the land every second year. At the end of the fallow period, the land is slashed and the plant residues/vegetation are burned as part of the field preparation.

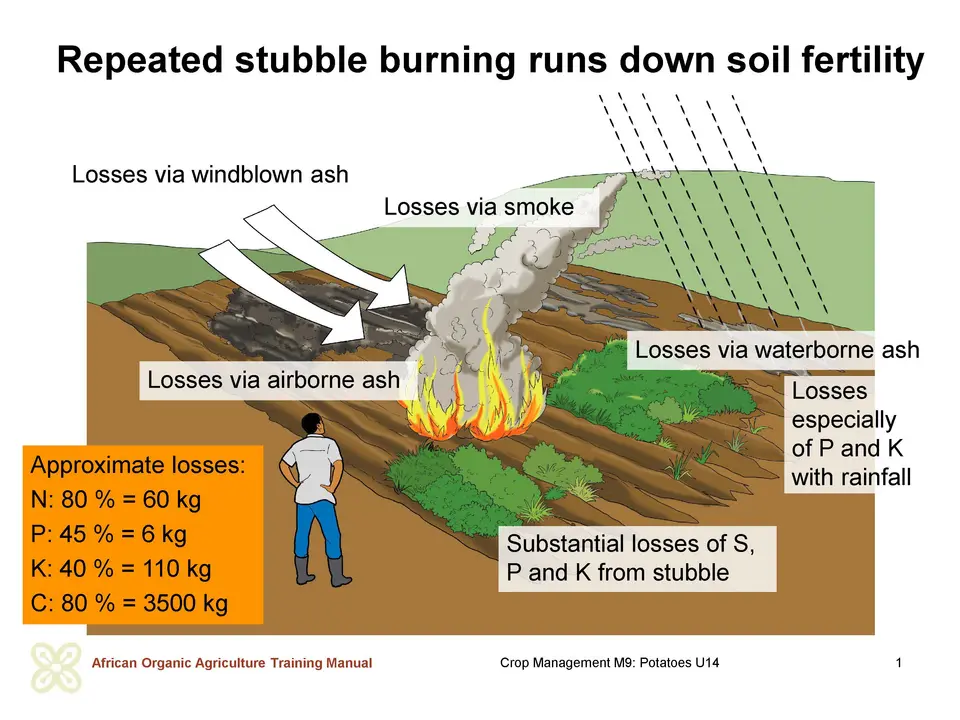

In the last decades, fertilization has relied on mineral fertilizers mainly. These fertilizers are costly, and even if their use shows positive results in terms of yields, it is well known that a significant portion of the nutrients is lost through leaching and erosion. The only organic fertilizer currently used in the western highland zone of Cameroon is chicken droppings. However, its price increases every year because of its high demand for the cultivation of vegetable crops. Compost production is not common. Only very few farmers know how to produce and use compost. All crop residues and fallow vegetation is burned rather than returned to the soil. Nor is any other biomass mixed to the soil to enhance its fertility. Burning of vegetation and/or plant residues destroys the remaining organic matter on the soil surface and in the top soil layer. Green manures are not commonly grown either. The majority of the farmers do not know the benefits of green manures and the nitrogen fixation capacity of legumes.

Crops grown in association with potatoes

Potatoes are generally grown every third year on the same plot, thus providing an adequate cultivation break which helps to control pest and disease build up in the soil, and to control soil nutrient depletion. However, most smallholder farmers in Cameroon generally do not consider the effect of the pre-crop on the potato crop. For example, many farmers grow maize before potatoes, giving priority to maize in the rotation. However, after maize, the soil is practically devoid of nutrients. In contrary, potatoes leave many available nutrients in the soil. This enables successfully growing of exigent crops such as maize, other tuber-crops or vegetables after potato.

Besides maize and potato, other vegetables like cabbage, beans, carrots, tomatoes, and peppers are cultivated in the potato growing areas. Crops such as avocados and bananas (cavendish and plantains) are common, too.

After harvesting potatoes, most farmers leave the ground/soil bare without any cover until the next growing season. During the dry season, such fields are extremely susceptible to wind erosion, and to water erosion when the first rains fall.

Pest and disease control practices by farmers

In Cameroon, the main pests and diseases in potato production are cutworm (Noctua), tuber-moth (Phtorimaea), late blight (Phytophtora), bacterial wilt (Pseudomonas) and black leg (Erwinia). Nematodes appear to be a lesser problem, but can build up in the long term if cropping cycles do not include crops that help to reduce nematode populations such as onions, corn or maize, millet, sorghum, sesame, cassava or Sudan grass.

Conventional potato farmers and cooperatives do use many commercial synthetic pesticides. Smallholder organic farmers do not commonly use commercial pesticides, mainly due to lack of availability in local outlets. Instead, many farmers use homemade phytosanitary products based on macerated leaves of papaya, Tithonia, wood-ash and charcoal. Soap and neem are frequently used as insecticides, and commercially available effective micro-organisms (EM) are used as an all-round plant protection agent. The efficacy of these products (with exception of soap and neem) has not been proven scientifically yet. Copper-based products are registered and available in Cameroon, but have not been used by potato farmers so far, even though they are effective against late blight and are allowed in organic agriculture. However, the efficiency of natural fungicides is challenged by regular rains during the main production season that wash off the fungicide coating soon after application. Disease tolerant varieties, healthy potato seed, appropriate crop rotation, suitable cropping periods and effective plant protection are thus vital for prevention of pests and diseases.

Yields

Average potato yields mostly are very low in Cameroon with 4 to 6 tons per ha (compared to a potential of 15 to 20 tons per ha) due to low soil fertility, using infested planting material, low use of farm inputs, and high disease and pest infection rates. Losses during storage, including losses in quality, are considerable. Due to low yields and high losses farmers cannot afford to invest into efficient farm inputs.

Marketing and storage

Long-term storage of potato beyond 2 to 3 weeks is difficult under warm and humid conditions. However, cooperatives and many farmers are used to store their potatoes for at least 3 months until the next planting season. Some cooperatives have built good storage facilities, which allow storage of tubers until the quantities in the markets are low and prices are high. To many farmers though, storage losses due to pests, diseases, and physiological disorders are a major constraint. Even if potatoes are harvested several times through the year and are continuously available, proper short-term storage would contribute to better quality of the produce.

Potatoes are an important source of income to most potato farmers in Cameroon, even if subsistence farmers may sell little of their crop. Marketing chains are well established, and often managed by women. Most smallholder farmers sell their produce individually on the local market. Depending on the region many farmers are organised in cooperatives, and these rather sell to retailers. Approximately three quarters of the potatoes are sold directly after harvest and are consumed locally. A minor part is exported to Cameroon’s neighbouring countries by traders. However, deteriorated roads and high temperatures discourage long-distance trading. Industrial processing of potatoes has not been developed yet, but development is starting. Soon the sector will create a considerable demand for potato varieties for processing.

So far, there is no organic certification scheme in Cameroon. Nevertheless, some farmers sell their potatoes as “organic”. However, on most local markets, no organic potatoes and vegetables are sold, neither produced according to organic guidelines, nor certified.

A survey by GIZ in Cameroon in 2018 year showed a considerable consumer demand for “pesticide-free” or “healthy” potatoes. But most consumers, traders and farmers have very little knowledge about the concept of organic food production. For raising or increasing the awareness of farmers, marketers, and consumers on organic potatoes, the development of national organic standards would be a valuable approach. It would bring more safety for producers and buyers of organic products, and encourage the development of the national organic market. National regulations on organic agriculture are being prepared by the government of Cameroon.

In addition to national regulations the survey by GIZ identified several measures for the promotion of organic markets and the assurance of quality organic potatoes. Such measures include education of farmers, increasing consumer awareness, and setting up of organic farmers’ markets and shops.

Discussion on challenges

Invite the farmers to describe their farming situation. Ask them, which challenges they face in general and especially related to potato production. Based on the prevailing challenges, define the next key steps for development of a more sustainable or organic production strategy.

What is organic farming?

What does “organic” mean?

“Organic” means “of plant or animal origin”. It also refers to the organisational aspect of an organism. For some people, organic agriculture is the kind of agriculture that uses organic manures or other natural inputs such as pesticides of plant origin, and that renounces to synthetic or chemical fertilizers and pesticides. For others, organic farming refers to agricultural systems that follow the principles and logics of a living organism in which the elements like soil, plants, farm animals, insects, the farmer are closely linked with each other. In this second view, organic farming depends on a thorough understanding and clever management of these interactions and processes.

However, organic farming is also defined by standards that explain the principles and permitted methods and list permitted inputs. While standards are well suited to define a minimum common understanding of the rules of organic agriculture, they do not explain how organic farming is practiced.

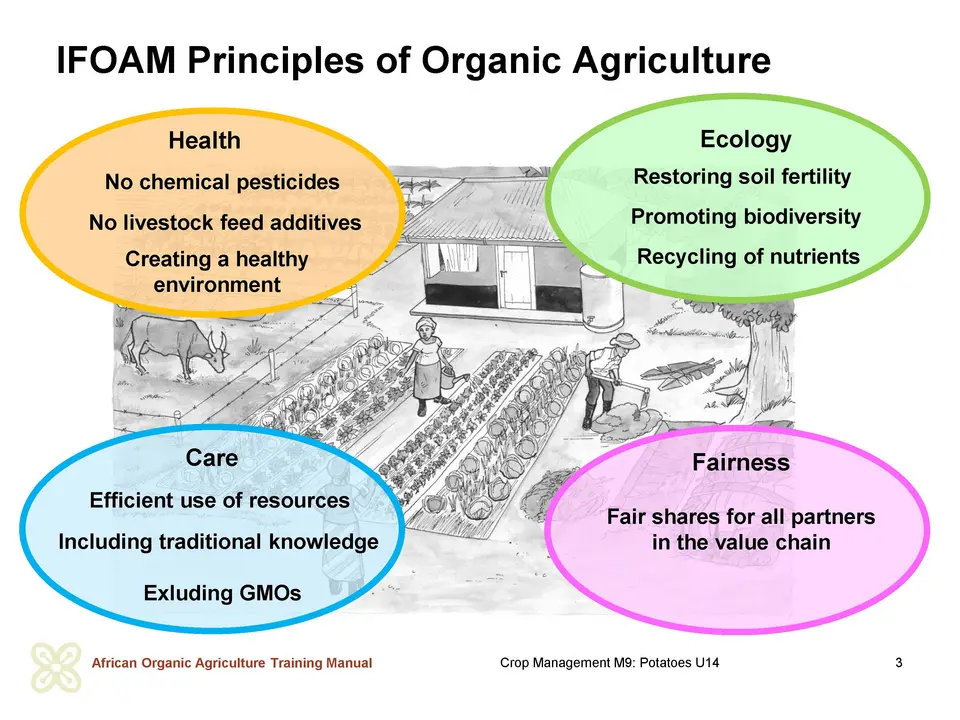

Principles and regulations

The principles of organic agriculture, as defined by IFOAM (International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements), the umbrella organisation for organic organisations worldwide, apply to agriculture in the broader context. They include the way farmers manage soils, water, plants and animals in order to produce, process and distribute food and non-food produce. IFOAM’s four basic principles health, ecology, fairness and care can be seen as the basis upon which organic agriculture is built. They give the basic orientation. The detailed rules and regulations are specifically elaborated by national legislations and private label organisations. For the European Union, a common organic legislation exists for all member states.

Working with nature

On a production level, organic farming relies on natural (or ecological) processes for plant nutrition, the stabilizing effect of a high biodiversity, production systems that are adapted to local climatic and soil conditions, and the efficient use of on-farm resources and local inputs mainly – just to name a few elements. At the same time, organic agriculture aims at combining in the best possible way traditional or local farming knowledge, new scientific findings and innovations by farmers and other players of the agricultural sector. Due to its approaches, organic farming is considered one of the most consistent concepts in the family of sustainable production systems.

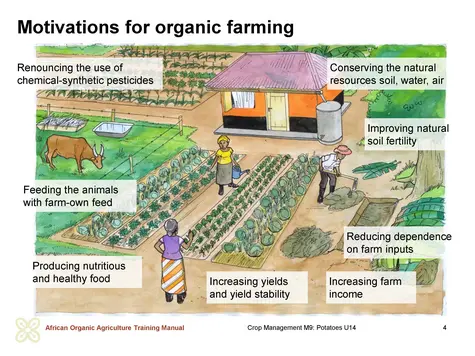

Organic farmers renounce the use of mineral nitrogen fertilizers, herbicides, synthetic pesticides, genetically modified varieties and feed, and restrict the use of veterinary medicines. This requires optimizing the growing conditions of the crops and systematic use of known preventive measures and positive interactions in the production systems to prevent damages by pests and diseases. For such an approach implementation of best agricultural practice adapted to the local situation is essential.

Thus, organic farming should not be confused with farming by neglect – thinking that the crops and animal can do without attention. In contrary, organic farming requires a differentiated understanding of interactions between the elements of a production system, intensive observation and willingness to constant learning.

In practice, a farmer may decide to only adopt “organic” practices such as composting, green manuring and/or the use of natural pesticides to improve fertility of his/her soils and to reduce the risks related to application of pesticides. Most farmers, who farm the “organic way” will apply for organic certification to market the products as “organic” and get a better price for them.

Main characteristics of organic agriculture

Organic agriculture can be characterised as follows:

- Organic agriculture was first defined early in the 20th century in reaction to rapidly changing farming practices using chemical pesticides and mineral fertilizers. In contrast to intensive agriculture with its high use of inputs, and its goal of minimizing the influence of nature and maximizing yields, organic farming orients itself on principles such as sustainability (best possible and efficient use of natural resources, enhancement of natural biodiversity and of soil fertility), openness, self-sufficiency, autonomy/independence, health, food security, and food safety.

- Organic farming methods combine scientific knowledge of ecology and modern technology with traditional farming practices based on naturally occurring biological processes. The methods are continuously further developed based on new findings on interactions between the elements of the agricultural production systems such as plants, soil organisms, natural enemies of pests or disease controlling effects of natural substances.

- Organic agriculture relies on fertilizers of organic origin such as compost, manure, green manures, bone meal and others.

- Organic agriculture relies on naturally occurring substances while prohibiting or strictly limiting synthetic substances. It excludes genetically modified organisms, nanomaterials, human sewage sludge, plant growth regulators, hormones, and limits antibiotic use in livestock husbandry.

- Organic farmers manage soil organic matter to maintain fertility of their soils based on (micro)biological activity and a good soil structure, and to encourage maximum water and nutrient conservation, minimal erosion and timely mineralisation of nutrients.

- Organic agriculture places emphasis on techniques such as cultivation of nitrogen fixing plants (mostly legumes) for fertilisation of crops, and planned rotation of crops to avoid development of soil-borne pests and diseases.

- Organic agriculture uses resistant or tolerant varieties, applies mixed cropping, creates good growth conditions, ensures crop hygiene, encourages insect predators, and uses biological pesticides (among other measures) to control pests and diseases.

- Organic farmers use crop rotation, cover crops and mulches to suppress weeds, while cultural, biological, mechanical and physical methods are applied to control weeds without using synthetic herbicides.

- Organic farming raises livestock and poultry for meat, dairy and eggs, providing animals with nature-like living conditions and natural, farm-own feed.

- Organic farming aims at minimizing negative impacts on climate change e.g. by encouraging binding of carbon dioxide in the soil, and keeping the soil covered with vegetation as much as possible.

- Organic farmers try to organise fair and long-term partnerships along the value chain for the marketing of their products. In order to cover possible additional costs and effort and to make sustainable investments in their farms, organic farmers are striving for a higher price for their products than the price for conventional products. Or they increase the added value in the company by processing their own products on the farm as far as possible.

- Organic farming is knowledge-intensive and can be labour intensive, if crop management requires manual weeding. Conventional farming, in contrary, is capital-intensive, requires more energy and manufactured inputs than organic farming.

You can find further information on organic agriculture and its definition here.

Introduction to organic farming

Introduce the farmers to the principles and characteristics of organic agriculture. Explain to them the difference between practicing organic farming by renouncing to chemical pesticides only, or by combining best agricultural practice with the application of specific organic practices such as composting and searching at optimizing the farming system.

Discuss possible benefits of OA in their context. What can be motivations of farmers to adopt organic farming principles and practices? Are there any constraints to adoption of organic farming?

Discuss chances and risks of organic farming in a local context.

Mention organic certification as a prerequisite for marketing organic products. Discuss the challenges and potentials of OA in their context.

For further information on the definition and the benefits of organic agriculture, and on the distinction of organic farming from other so-called sustainable agriculture systems such as integrated Production (IP), fair trade labels, Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) and Low External Input Sustainable Agriculture (LEISA), and other farming concepts such as conservation agriculture, agroforestry and permaculture please see Module 1 of the African Organic Agriculture Training Manual at www.organic-africa.net > Training Manual.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.