Improving cotton yields

Cotton yields are mainly determined, apart from the farmers’ skills, by climatic factors such as temperature, sunlight, and availability of water, the soil qualities (structure, texture, nutrients and biological life), the seed variety as well the situation regarding pests, diseases and weeds. Under good conditions the cotton plant may produce 1 to 2 tonnes of seed cotton per hectare in tropical Africa. However, if only one of the favourable conditions is lacking, yields are drastically reduced. If the unfavourable conditions are only short term (few weeks), the cotton plant may recover through compensation.

Group discussions on possibilities for improvement of cotton yields

Form small groups of 3 or more farmers and let them suggest the different ways to improve cotton yields. Let them note down their contributions on paper for discussion with the rest of the group in a plenum.

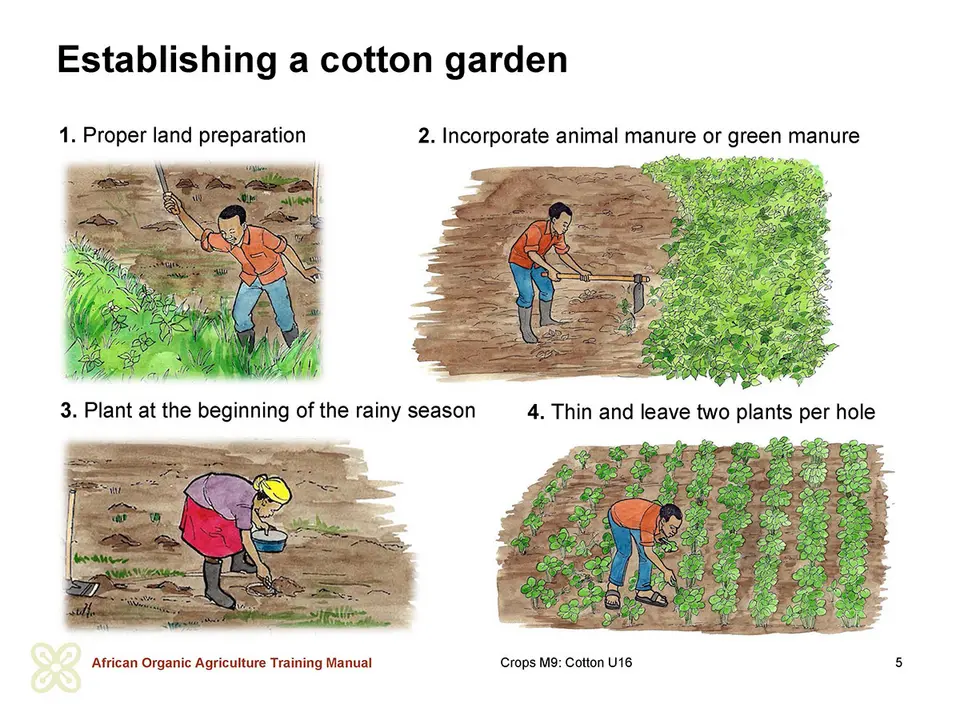

Establishing a cotton garden

Cotton is highly sensitive to excess water and water logging, which causes a reduction in yields through boll shedding, even when the plant appears to be unaffected. Cotton plants prefer deep, well-drained soils with good nutrient content. Ideal soils are clay-rich, vertisols (also called ‘black cotton soils’). This ensures that the tap roots of cotton plants can penetrate up to 3 meters in such soils and hence are able to sustain short periods of drought. However, cotton is also grown on less ideal sites with shallow, sandy soils, both under irrigated and rainfed conditions. This will, however, require well-adapted varieties and solid management practices.

Land preparation should be done early while incorporating green manure or animal manure before planting. Land preparation should also ensure that weeds are substantially removed to prevent an excessive growth of weeds during the early growth phases of the cotton crop. Planting should be done as soon as the rain season begins to ensure that the planted seeds get adequate moisture for germination and growth. Cotton is either planted on flat rows or ridges. Ridges are used in soils that are difficult to drain, and in regions with little rainfall, as this helps to conserve water under dry conditions and aid drainage under wet conditions.

In small-holder cotton production, cotton planting is done by hand and about 3 to 4 seeds are planted per hole in flat rows or ridges. Thinning is done when the plants are 6 to 10 cm high, leaving the strongest two plants per hill. The optimum spacing depends on the size and fruitfulness of the plant permitted by local conditions. The optimum spacing ranges from 20 to 50 cm within rows and 60 to 90 cm between rows, with one or two plants per hill.

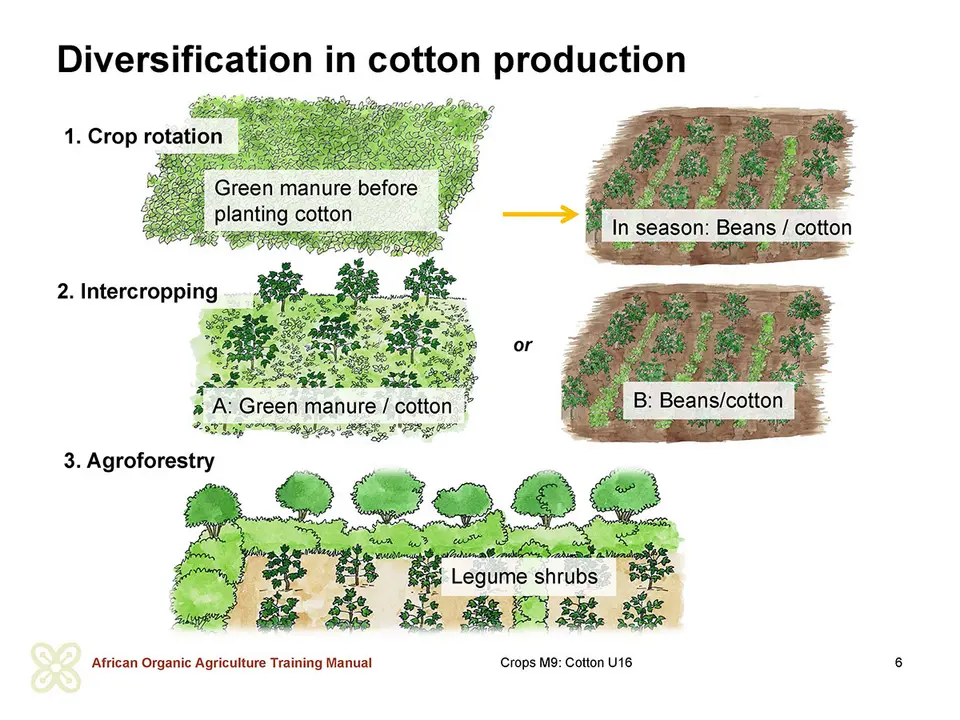

Diversification in cotton production

Cotton is by nature a perennial crop, but it is commonly grown as an annual crop. Contrary to most cereal and leguminous crops, cotton is deep rooting. Its vertical tap root gives the plant access to water and nutrients in lower soil layers. This makes it a good rotational crop, and one that is relatively tolerant to drought and variable rainfall.

a. Crop rotation

Cotton must be grown in rotation with other crops to maintain fertility of the soil, break the development cycles of soil-borne pathogens and prevent the spreading of weeds. Cotton should not be grown after cotton in the same field. Instead another crop should be grown at least for one, but preferably for two seasons, before the next cotton crop.

Cotton rotations should include legume crops such as mung bean, cow pea or chick pea for harvesting or a green manure crop such as sun hemp or cow pea, to be cut and ploughed back into the soil before flowering. Pulses like mung beans, soybean, chickpea, pigeon pea and groundnuts increase the nitrogen content in the soil by fixing nitrogen from the air. But they can also be marketed to increase farm income. Suitable crop rotation patterns with cotton depend on the climatic conditions, market requirements and availability of land.

b. Green manures and intercropping

When cotton is intercropped with maize, sorghum, beans or peanuts, pests find it more difficult to move from one host plant to another, and they are controlled by a number of beneficial insects hosted by the intercrops. Some examples are:

- Maize planted in every 2 rows of cotton attracts the African bollworm.

- Sunflower or cowpea sown in every 5 rows of cotton attracts moths when planted as trap crops.

- Castor bean (Ricinus communis) also attracts caterpillars.

- Rice when rotated with mung bean and cotton disrupts the life cycle of pests attacking these crops.

For best distracting effect, planting of intercrops, trap crops and border crops should be timed such that they flower at the same time with cotton. Intercrops are usually allowed to mature and are cut and used as mulching material after the seeds are harvested.

Diversification of crops furthermore reduces vulnerability to crop failure and to fluctuating prices. It also helps to prevent shortage of labour in peak seasons, as labour requirements are more evenly distributed throughout the year.

Green manures improve soil fertility and can act as trap crops. Green manure crops like sun hemp (Crotolaria juncea), jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis), Lablab (Lablab purpureus) or velvet beans (Mucuna pruriens) are usually sown between the rows after cotton seedlings emerge. They are cut before or at the time of flowering, and are either used as mulch or incorporated into the soil.

Both green manure and intercrops have the following benefits:

- They distract pests from the cotton crop (especially sucking pests), attract and host beneficial insects.

- They take up nutrients from the soil and build-up organic matter, which would otherwise be lost through leaching. The added organic matter builds better soil structure, water retention and overall fertility.

- Leguminous green manure crops and intercrops fix nitrogen from the air and make nutrients available to the cotton crop.

- They suppress weed growth and protect the soil from soil erosion through rain or wind.

- They provide additional yields or fodder for livestock.

- On the other hand, green manure and intercrops do compete with the cotton crop for water, light and nutrients. Thus, appropriate timing of the sowing and cutting is very important in order to get maximum benefit with minimum competition.

c. Agroforestry

In areas with heavy wind and frost, agroforestry with wind breaks should be considered. Different trees are needed to break the wind, protect from strong rains, and provide shade, mulch and fodder. Useful species are Leucena leucocephala, Moringa oleifera, Faidherbia albidia, Neem and other adapted trees, which do not consume too much water and ideally provide additional food and fodder as well as serving as mulch. However, the trees need regular pruning because the cotton plants do not tolerate much shade.

Group activity on diversification in cotton fields

Ask the farmers which crops are commonly grown together or in rotation with cotton. Summarise the results of the discussion and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the suggested options, based on the experience of the farmers. At the end of the discussion, try to agree with the farmers on the most suitable crop rotation and intercropping patterns for local conditions.

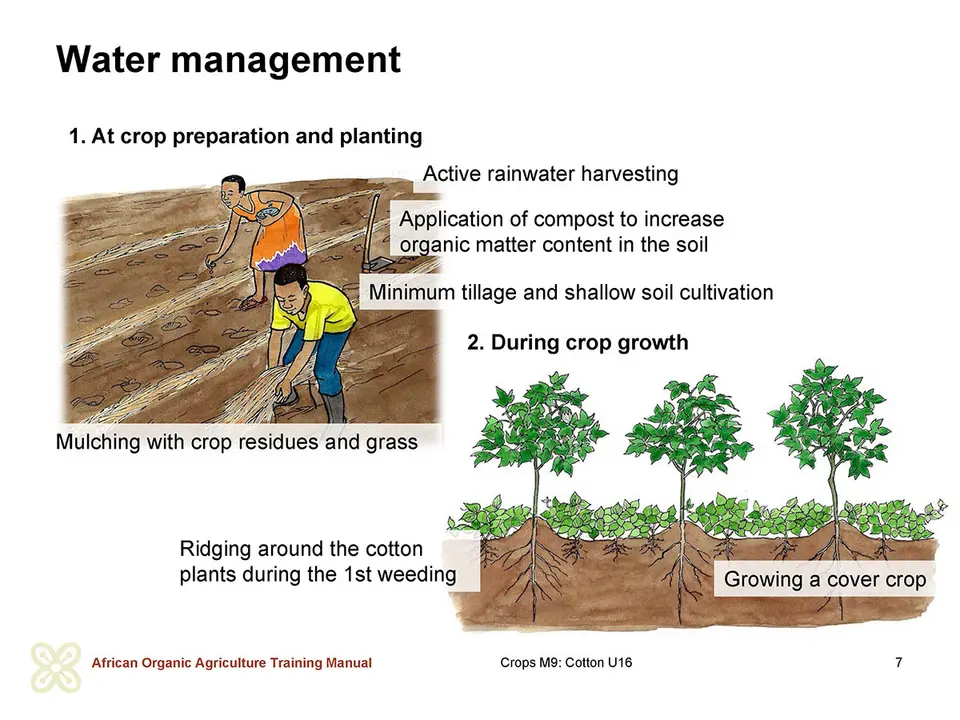

Improvement of water availability

Cotton has high water requirements for boll setting and renewed growth, but dry conditions are also needed for ripening and harvest. In rainfed cotton production, major emphasis should be given to increasing the infiltration of rainwater into the soil and to its conservation. The following measures contribute to increased availability of water:

- Application of compost and organic manures helps increase organic matter content in the soil, which is known to improve soil structure, hence increasing water infiltration and water retention.

- Minimum tillage and shallow soil cultivation (hoeing) reduces water evaporation from the soil. Ridging around the growing plants is also a common practice to conserve water.

- Covering the soil with mulching materials helps to preserve humidity in the soil and to prevent water loss, while enhancing increased biological life in the upper-parts of the soil.

- Active rainwater harvesting through pits or trenches leading to wells can help to recharge groundwater levels and thus to improve the availability of irrigation water.

Where little irrigation water is available, alternate furrow irrigation can still help irrigate the crop. If rain fails after the seedlings have germinated, it can even be worth saving them through bucket irrigation, plant by plant.

Virtually all cotton cultivation in sub-Saharan Africa is rainfed. Irrigated cotton would technically be possible in some areas in very dry regions with less than 600 mm of rain per year. The resulting extra yield from irrigation covers the cost of irrigation.

Optimizing weed management

Weed management strategies in cotton include proper crop rotation, timely soil cultivation, proper sowing density and ploughing techniques to remove the weeds. Weeds are important in cotton fields during certain parts of the growing season:

- In the initial stage of plant growth, weeds catch nutrients which otherwise would be lost through wash out. These nutrients are returned to the soil and made available to the cotton crop when the weeds are cut. Once the cotton crop has developed a dense stand, weeds usually will remain below a level where they significantly compete with the main crop.

- Some weeds are important hosts for beneficial insects, or act as trap crops distracting pests from the cotton plant. Careful observation of weed populations and the use of shallow soil cultivation combined with selective hand weeding usually is enough to keep the weeds under control.

Weeds should be controlled well during land preparation before sowing. In about 6 weeks after sowing, all emerging weeds that emerge should be removed. This helps to reduce later weeding requirements and reduces weed competition with the young cotton plants. Ridging is normally done once the cotton plants are about 0.5 to 1 meter high and this can be combined with a last weeding session. A positive side effect of ridging is the reduction of water evaporation.

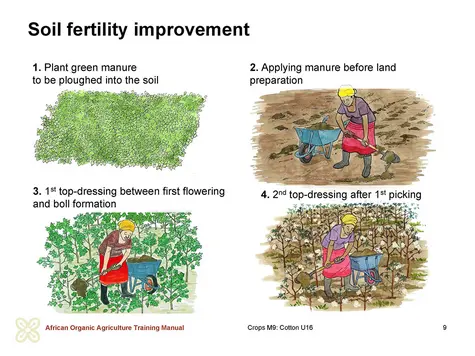

Soil fertility improvement

The right strategy to improve and maintain soil fertility in cotton depends first and foremost on the soil types present in a farm.

Light or shallow soils usually have a lower water retention capacity and lower nutrient exchange capacity than deep or heavy soils. The application of compost or other measures in increasing soil fertility is important to increase water holding and nutrient supply and to improve the structure of the soil. Intercropping of more drought resistant crops like sorghum, sunflower, sesame or castor can help to reduce the risk of crop failure. Soil cultivation should be shallow and kept to a minimum in order to avoid soil erosion and enhance build-up of organic matter.

In deep or heavy soils such as black cotton soil, an intensive production system can be established with sufficient inputs of organic manures, intensive crop rotation and green manuring. Frequent shallow soil cultivation helps to improve soil aeration and nutrient supply. It also reduces evaporation and suppresses weeds. When the cotton crop is well established after 6 to 9 weeks, it is recommended to apply additional organic manure such as vermi-compost or oil cakes and to earth up ridges in order to accelerate decomposition and to bury weeds.

Attention must be paid that the soil is not prone to water erosion. In case of the risk of eroding contour lines or terraces, other soil conservation measures are highly recommended as the basis of improving soil fertility.

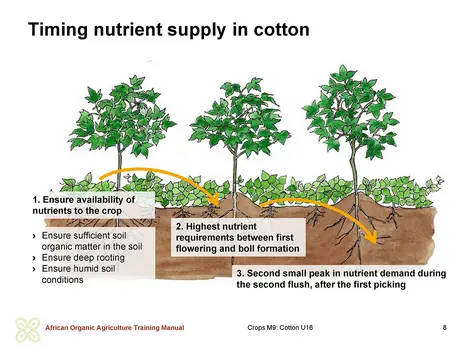

Manure or compost should also be applied before soil cultivation such that during ploughing, the organic materials are brought into soil. Well composted manure or other organic fertilizer can replace the extracted nutrients and contribute to maintenance of soil fertility. Availability of nutrients to the crop, however, depends on other factors as well, such as sufficient soil organic matter and active soil organisms, deep rooting of the crop and humid soil conditions. Cotton’s nutrient requirements are highest between first flowering and boll formation. A second small peak in nutrient demand is during the second flush, after the first picking. A top-dressing of organic manure during this critical growing period contributes to increasing yields.

Discussion on local soil types

Share with the farmers their experiences with the prevalent soil types in the region and try to agree on characteristics of these soils and their reaction to approaches to improve their fertility.

Discussion on suitable on-farm and off-farm manures

Ask the farmers, which manures and fertilizers are available on their farms, and which are available from nearby. Discuss with them, how nutrient supply can be further improved and which alternative sources of nutrients could be used.

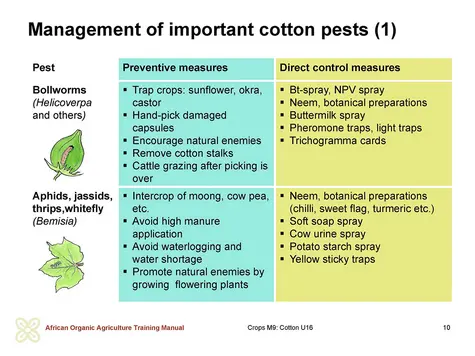

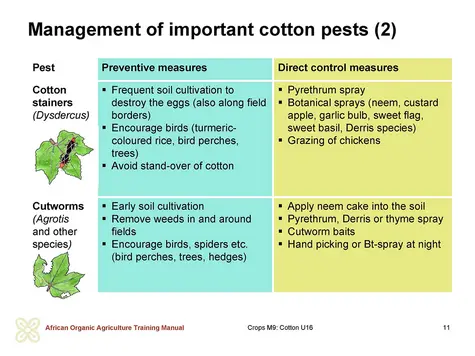

Pest and disease management

Cotton has a wide range of pests that can lead to 50 to 90 % yield losses. In most of the semi-arid tropical regions, diseases are not a big problem in well-managed organic cotton fields.

Early observation, combined with the required knowledge of the ecology of the insects and the tools for monitoring (pegboard, biopesticides and advice) as well as a professional support from scientifically trained experts will be required in order to manage the risks effectively.

Cotton research has done a great deal to identify the insects that ‘threaten’ the cotton production system. Researchers in almost all sub-Saharan African countries can claim that the list of important cotton pests consists of:

- Early-season pests: Aphids (Aphis spp.), Whiteflies (Bemisia spp.), Cotton leafroller (Sylepta), Lygus bugs (Lygus), etc.

- Mid-season pests: Cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera), Spiny bollworm (Earias spp.), Cotton leafeater (Spodoptera spp.), Red or Sudan bollworms (Diparopsis spp.), and/or depending on the region Pink bollworm (Pectinophora gossypiella) and False codling moth (Cryptophlebia leucotreta).

- Late-season pests: Aphids (Aphis spp.), Whiteflies (Bemisia spp.), Cotton strainers (Dysdercus spp.), etc.

Selected examples of important cotton pests:

American bollworms (Heliothis (or Helicoverpa) armigera) - The young larvae feed on tender leaves, buds, flowers and later bore into the bolls. While feeding, its head and part of the body are inside the boll. They deposit faeces at the base of the entrance hole. Eggs are pinhead-size and yellowish-green in colour. They are found singly laid on the surface of the leaves. Larvae vary in colour from bright green, pink and brown, to black, with lighter undersides. Alternating light and dark bands run lengthwise along their bodies, the heads are yellow and the legs are almost black. Mature larvae drop to the ground to burrow into the soil to pupate. Pupae are yellowish-green and turn brown as they mature. Adult moths are grey to brown in colour and have dark spots on the front wings. They are active at night and hide in vegetation during the day. The total development period from egg to adult is about 34 to 45 days.

Cutworms (Agrotis spp.) - The larvae cut seedlings often at ground level. They can be found in the soil down to a depth of about 5 cm near the host plant. Cutworms always curl up when disturbed. They feed only at night. Eggs are tiny, pearl-white, round and have a ridged surface. The full-grown larva is brown or brownish-black with a tinge of orange. The pupa is black or brown in colour. The adult has dark brown forewings with distinctive black spots and white and yellow wavy stripes.

Aphids (Aphis gossypii and others) - Aphids are important pests in fields with low populations of natural enemies, high manure application, or where crops suffer water stress. Heavy infestations cause crinkling and cupping of leaves, defoliation, square and boll shedding and stunted growth. If the infestation is not too high, the plant can compensate for the damage. Honeydew excretion causes sticky cotton lint and thus problems in spinning. Aphids produce large amounts of a sugary liquid waste called honeydew. A fungus, called sooty mould, grows on this honeydew, turning leaves and branches black. The eggs are very tiny, shiny black and are found in the crevices of bud, stems and bark of the plant. Winged adults are produced only when it is necessary for the colony to migrate.

Cotton stainers (Dysdercus spp.) - Cotton stainers suck sap from flowers, buds and bolls of cotton. In case of high infestation, the bolls open insufficiently and the lint quality is reduced due to stains resulting from fungal infections. When sucking on immature seeds, cotton stainers transmit fungus on the immature lint and seed, which later stains the lint with typical yellow colour, hence the name ‘cotton stainers’. Heavy infestations on the seeds affect the crop mass, oil content, germination capacity of the seed and marketability of the crop. Cotton stainers are, however, usually not a major problem in organic fields.

Cotton strainers lay their eggs into the soil or under plant debris. Nymphs look similar to their adult counterparts, but have no wings, meaning that they can only attack seeds in open bolls. The adult cotton stainers are true bugs with piercing and sucking mouthparts. They can even suck on seeds in closed bolls. Their colour varies from bright red to yellow to orange, depending on the species.

Discussion: Pest management in cotton production

In order to understand the local pest situation and to be able to recommend suitable measures, ask the farmers the following questions:

- What are the most important cotton pests in their area?

- Which preventive and direct methods are used to keep the pests below the economic threshold level?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of each method? Are there new methods to be tested in field trials?

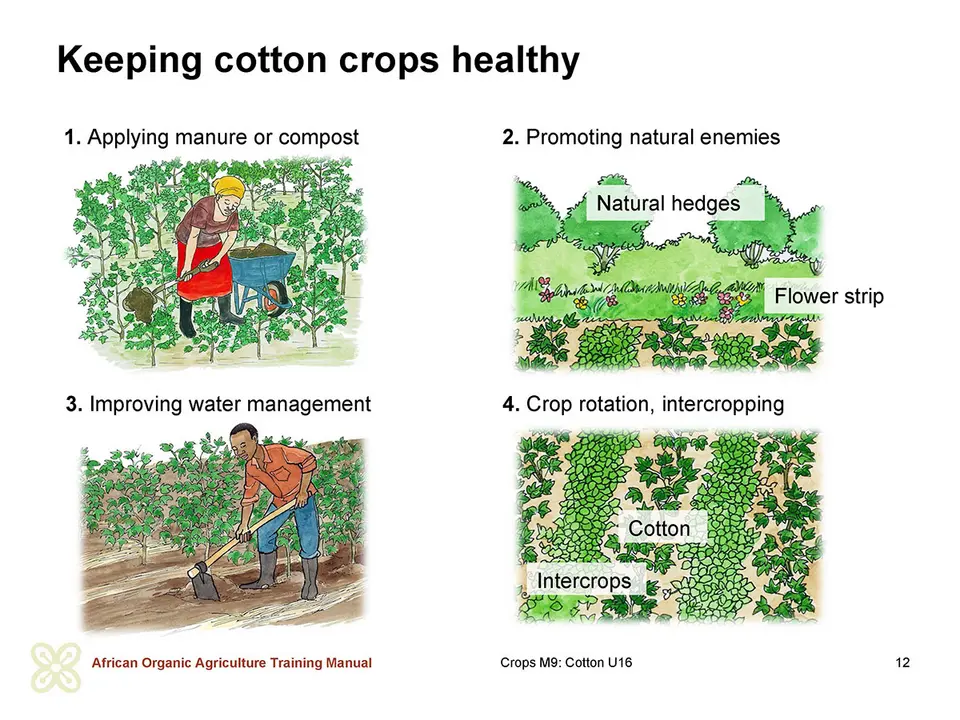

a. Keeping your cotton crop healthy

Healthy cotton plants have some means of defence. They compensate for affected shoots and leaves through additional growth. They also produce substances such as gossypol that deter insects from eating them. Organic cotton farmers, therefore, enhance plant health and natural regulation of pest populations by applying the following practices:

- Varieties with hairy leaves and higher gossypol content are less susceptible to pest attacks and are thus recommended.

- Fertile soil and a balanced nutrition based on applying compost and organic manures enhance plant health. Shallow soil cultivation and careful irrigation avoiding dryness as well as water logging contribute to establishing favourable soil conditions.

- Diverse cropping systems and natural habitats around the fields enhance development of natural enemy populations like birds and beneficial insects, which help to control pests. Crop rotation, intercropping and trap crops are very effective measures to prevent pests in cotton. Intercrops like pulses, flowering plants and trap crops like sunflower or maize distract pests from the cotton plants. Experience from Tanzania shows that the sunflower is an efficient trap crop for the American bollworm, as the pest prefers sunflowers to cotton. It is even reported that on sunflower plants, bollworms attack each other (cannibalism). It is, therefore, recommended to sow one row of sunflowers every 15 meters at the same time as the cotton crop. In Africa it was observed that beneficial ants visit the sunflower plants and efficiently control bollworms.

If preventive measures are properly implemented, pest problems in organic cotton are minor. A certain level of pest attack will not significantly reduce the cotton yield. Below the economic threshold, the cost and effort to control the pest is higher than the damage it causes.

Diseases are normally not an issue in organic cotton systems, as they are prevented with appropriate crop rotation and using healthy seed and adapted varieties.

b. Threshold levels and monitoring through observation

Regular monitoring of pest levels in the cotton fields during the critical growth period beginning approximately 4 weeks after sowing and lasting until the second harvest is a key to successful pest management in organic cotton. Monitoring helps to find out when a pest population reaches the economic threshold and thus direct control measures become necessary. The indicated threshold levels of the major cotton pests in following table may need to be verified and adapted for use under local conditions.

| Pest | Threshold level (according to US practices) |

| American bollworm (Helicoverpa) | 1 larva per 5 plants, 5–10% damage to bolls or 15 flared squares with a hole on 30 plants |

| Pink bollworm (Pectinophora) | 5% rosetted flowers |

| Spotted bollworm (Earias) | 1 larva per 5 plants, 5–10 % damaged shoots or bolls |

| Cotton leafworm, tobacco caterpillars (Spodoptera) | 2 larvae per 10 plants or 3 skeletonized leaves with young larvae |

| Cotton stainer | 2–3 individuals per leaf |

| Aphids | 20% infested plants |

| Jassids | 5–10 insects per plant |

| Thrips | 5–10 nymphs/adults per leaf |

| Mites | 5% infested plants |

| Whitefly | 5–10 nymphs/adults per leaf |

For monitoring American bollworm populations, farmers in some African cotton projects are using simple pegboards for scouting.

Use of a pegboard in scouting for American bollworms:

- Scouting is started 8 weeks after germination and is repeated weekly until the bolls open.

- At scouting, the plants are checked by crossing the cotton field on two diagonals, starting 5 steps inside the field from one corner.

- Every 5 to 10 steps on a cotton plant, all newly opened flared squares (those with changed shape due to bollworm attack; not dropped squares) are counted. For each flared square, the marker on the pegboard on the right part of the pegboard is forwarded 1 hole.

- After finishing with a plant, the marker in the left part of the pegboard is forwarded 1 hole.

- On each diagonal, 15 plants are examined, moving the markers forward accordingly. After inspection of plants on the first diagonal, plants on the second diagonal are inspected.

- The procedure is continued until 30 plants have been inspected or until 15 flared squares have been found. When the stick for the flared squares reaches the red zone, the economic threshold is reached and spraying of a natural pesticide is recommended for the same day. No spraying is recommended, when less than 15 flared squares were found.

c. Direct control of major cotton pests

Direct measures such as spraying botanicals such as neem or Derris, or microbial sprays containing Bt or NPV should be used only when the preventive measures prove insufficient to keep pests below the economic threshold.

The best time for spraying is in the morning hours between 8 and 11 AM. Spraying after it rains or when the plants are still wet is not recommended because effectiveness is reduced.

Major pests in tropical cotton cultivation are bollworms (Helicoverpa, Pectinophora and Earias species). If bollworm populations reach the economic threshold, different direct control methods are available. Microbial preparations Bt and NPV can be used against American bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera). Pheromone traps and dispensers attract the adult moths and thus prevent the laying of eggs. Spraying of neem formulations and locally prepared botanical extracts is a cheap method to control bollworms and other pests. In India, organic farmers use diluted cow urine and buttermilk sprays with good success. However, most of these sprays also affect beneficial insect populations and thus should be used only when necessary.

Aphids (Aphis spp.) and whiteflies (Bemisia spp.) are typical secondary pests. They have a wide range of natural enemies under natural growing conditions. Where no synthetic insecticide sprays are used, aphids and whiteflies normally maintain lower numbers. However, if organic cotton fields are small and scattered around a conventional cotton growing area, the fields may come to act as refuges for aphids and whiteflies from nearby sprayed conventional fields.

Field demonstration: Monitoring bollworm with the help of the pegboard

Explain the concept of monitoring and the use of the pegboard with the help of Transparency 12. If possible, visit a nearby cotton field and demonstrate the use of the pegboard for monitoring American bollworms or other insects.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.

tap and then scroll down to the Add to Home Screen command.